REVERSAL OF FORTUNE

In Henry Fool, Hal Hartley weaves a Faustian epic of fate and destiny, of a garbage man becoming a millionaire poet, and a vagabond poet settling down. But with seven features and a hallmark style, Hartley’s fate as one of America’s preeminent auteurs seems pretty much sealed. Ray Pride speaks to him about his career, art, and scatological humor.

Writer/Director Hal Hartley Photo: Richard Sylvarnes.

Relationships and romance: trouble and desire. Thematically and visually, Hal Hartley’s seven features and handful of shorter pieces are remarkably consistent in tone and mood. In vaudeville, they called it "shtick." But in film, critics see a signature style and quickly dub the unwitting director an "auteur." Long Island native Hartley is well aware of this process. He prefaced the Faber and Faber paperback of the Flirt screenplay with a few words from Jean Renoir: "Everyone really only makes one film in his life, and then he breaks it into fragments and makes it again with just a few little variations each time." With one of the most immediately recognizable styles among directors working today, Hartley began developing a small but devoted following with his 1989 debut, The Unbelievable Truth and continued to refine his style through Trust, Surviving Desire, Simple Men, Amateur, and Flirt. Henry Fool, his seventh feature, moves beyond the deadpan despair of his well-groomed heartsick romantics into a kind of intimate epic about the convergence of reticent Queens garbage man Simon Grim (James Urbaniak) with Henry Fool (Thomas Jay Ryan), a vagabond and charming braggart who wanders into the lives of Simon’s family, preaching the virtues of the artist’s life, cadging loans for six-packs and bedding various members of Simon’s household.

While the Faustian comedy of Henry Fool resembles Hartley’s earlier work in formal terms — spare, geometric frames commonly captured in natural light; extremely good-looking actors uttering aphoristic comic dialogue in the driest of deadpan; all underscored by melancholy guitar pop — its engagement with a larger world of concerns marks an interesting turn for the almost 40-year-old director. Did anyone expect the sleek, cosmopolitan surfaces of a Hartley film to reflect back a garbage man who would storm the world with a book-length pornographic poem? Where a gruffly entertaining character would admit to statutory rape and offer up his side of the story? Or where a riff on one of the most notorious scatological scenes from Dumb and Dumber would bloom into a moment of deepest tenderness? When Hartley says, "What I want is for people to reassess their assumptions on a moment-to-moment basis," he is speaking not only of his work but of the world outside his lustrous, often-hermetic world.

Hartley’s independence comes through as forcefully in economics as esthetics. Great popular success in the larger world has been elusive for Hartley’s movies, but he has been able to maintain his career by working with diverse financing and comparatively small budgets. Hartley is willing to pursue his work in forms other than theatrical features, whether smaller-budgeted films or even video, the format of his most recent work, The Book of Life.

Filmmaker: In the realm of American independent film, you could almost be considered the "last auteur," having constructed a body of work with similar concerns and an identifiable, idiosyncratic look and sound. Few filmmakers who’ve arrived on the scene after you have developed such a distinct style. You once said that an agent condescendingly asked you, "Don’t you want to make real movies instead of these little things?"

Hartley: Yeah.

Filmmaker. So, are you worried about continuing to be able to make "Hal Hartley" films?

Hartley: Well... I don’t really have any fears. I’ve always been the type of person to think of my work not as a series of presentable items or products but as a continuum. I have certain interests as a creative person, and I’ll probably spend my entire life pursuing them. I think that that’s what leads people to call it "auteur work." Sensible budgets – not necessarily small – offer a degree of freedom that I see others losing because they take more money from outside sources. I don’t feel constrained by small budgets. I don’t feel that the things that I want to make films about or the way in which I want to make them are necessarily constrained by a lack of financing. I think a consistency of momentum is more important if one thinks of one’s work as a life-long commitment to a particular type of creative activity. The little films, like Book of Life, a feature on digital video I just made for French television for $350,000, are certainly just as significant to me as Henry Fool, which was made for $1 million in 35mm. It’s important to think that way because it puts the work first, not the career.

Filmmaker: Larger budgets can lead even serious filmmakers to make horrible compromises.

Hartley: Yeah, there’s the desperation that a nice, responsible person will have if someone gives them a bunch of money. They are going to want to promise [the financiers] certain things, and they are going to work hard to get these people these certain things, because that’s their promise. Whereas it could be much better to explore more, to have the opportunity to discover while you are making the film – to not just make illustrations of what’s written in the script, but to actually discover things in the shooting.

Filmmaker: How have things changed since you began? It seems like you once had, if not the cushion, the advantage for your first few features of finance from sources such as American Playhouse and certain foreign companies. There’s no foreign money apparent in the Henry Fool credits.

Hartley: Well, things have changed with American Playhouse going out [of business]. We never had that much money. None of [my earlier] films were made for a quarter of the budget of most of my contemporaries. We’re talking about getting maybe $200,000 or $300,000 from American Playhouse. That’s still extremely small. What has made it difficult [today] is that European investors are more reticent about putting money into an American art film without some American money being put in first. And Lindsay [Law] and American Playhouse functioned in that capacity.

Filmmaker: In the press notes for Henry Fool there’s almost a car crash of ideas mentioned. There’s first the concept of an "intimate epic," how the story stays very close to its characters but brings up so many concepts, and then there’s the influence of stories such as The Devil and Daniel Webster, the Faust legend, the story of Kasper Hauser, the example of how James Joyce was a mentor to Beckett. And, in the film, the fact that we never see Simon’s controversial manuscript is kind of like the tease of never finding out what’s in the little box in Belle de Jour. I thought I was reaching for that connection until I realized that Henry’s parole officer is named Officer Buñuel. But I’m sure I was straining too much when I saw Susan Sontag’s gray stripe in Simon’s mother’s hair!

Hartley: [Laughs.] That wasn’t intended!

|

| Thomas Jay Ryan as Henry Fool and Parker Posey as Fay |

Hartley: I don’t think about that, really. You know, people are free to make whatever they want out of a piece of work. I didn’t want to make an intertextual movie where one needs to know the mythology of Faust and Paradise Lost, or whatever other things people think I’m connecting to. Those elements were just helpful in crafting a story. My desire was to make a contemporary story that conveyed in broad strokes, sketched in, an impression of the culture we live in now. I wanted it to be sufficiently universal, sufficiently mythic in that regard. I usually go to the classics, because if I’m going to try to steal stuff from anybody, I’m going to try to steal it from the big shots.

Filmmaker: New to your work in this film is all the vulgarity – the vomiting scene, the violently loud eruption of the diarrhea scene. Your use of scatological humor is much more disturbing than what we’ve seen in the recent wave of "gross-out" movies. I saw the film the other day and [a middle-aged colleague] who was a big fan of Dumb and Dumber did not respond well to those scenes.

Hartley: Well, a film like this attacks what [those critics] stand for in our culture. I unapologetically am out to piss those kinds of people off. Our culture is infatuated with this Dumb and Dumber stuff. I wanted to talk about more serious things [in this film], but I didn’t want to do it in an academic atmosphere. I didn’t want Henry and Simon to be wearing tweed coats and have Ph.D.s. They needed to be, to a certain degree, disgusting. It was important that Henry be disgusting and that we experience a lot of disgust around him. I think the shitting scene is one of the most sophisticated comic things I’ve ever done. There’s a complexity that keeps the sophomoric scatological humor legitimate.

Filmmaker: You’ve commented before that movies are the only medium in which a work of art is considered "done with" in one go. You might know a piece of music by Beethoven well, but that doesn’t mean that you don’t listen to it again.

Hartley: That old modernist idea can apply to film and literature. What compels us to continue watching is not the expectation of being surprised but that a piece of work is conceived of and crafted in such a way that the excitement of watching it does not evaporate after going through it once. Music is the best example. We go back to a piece of music and can’t wait for that shift from major to minor to happen. It’s an appreciation of the structure and form of art. But in film, [that modernist concept] is popularly reversed. If a film doesn’t reveal itself all in one go it is somehow perceived of as a failure. Film is one of the few arts where that [idea dominates] – once you’ve seen it, it’s dead. I’d like to make films that get past that. I think that fiction is perfectly capable in any medium of achieving this musicality. That’s not what I was after in Henry Fool but it was what I was after in Flirt. And a little bit more in Amateur, perhaps.

Filmmaker: How is Henry Fool different, then?

Hartley: This is just consciously more emotionally obvious. It wants to be the kind of movie that gets people excited in a more [accessible] way. I felt the desire to make something like that. And I haven’t really done that since Surviving Desire or Trust.

Filmmaker: Does it involve putting more attention and time into foregrounding the pleasures, making them immediately graspable?

Hartley: Yes, that’s part of it. It’s letting the audience know exactly how to read a scene. To a degree, you leave out the opportunity for them to make of a scene what they will. There’s always that dynamic in telling any story. In Henry’s case, the entire conceit of the movie is a little bit like that. I wanted to create a situation where the audience was constantly engaged because their moral assumptions are being challenged by this guy.

Filmmaker: In the beginning of the film, Henry’s a large personality, a "movie-movie" rowdy, and then he says that he has been with an under-aged girl, went to jail for it, and expresses no contrition. In fact, he says that "she asked for it."

Hartley: Right. When you get to that point, do you still want to continue liking him? I think it’s a totally legitimate response to say, "I can’t go with this movie anymore because the filmmakers aren’t judging this guy. We’re still expected to like him." But I see people watch the film, and they’re challenged and upset. They keep watching because there seems to be something important about that challenge. What I want in a movie like this is for people to reassess their assumptions on a moment-to-moment basis.

Filmmaker: Henry tells absurd stories about adventures in some remote jungle, so everything he says we can read as a lie. Yet when he talks about the girl, and it’s partly because you’ve underlined it by the way it’s shot, you assume that someone who admits such a foul transgression must be telling the truth.

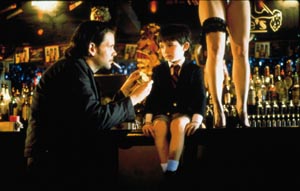

|

| Ryan and Liam Aiken as Ned in Henry Fool |

Filmmaker: Everything has to be big and loud for Henry Fool. He’s like that wonderful character of Alan Rudolph’s, the Keith Carradine character in Choose Me.

Hartley: Oh yeah! Exactly. There’s also a character in literature, the trickster. He’s someone who is necessary precisely because he can’t be trusted – he keeps everybody else on their toes.

Filmmaker: How did you arrive at using masters of two characters who both face the camera? Joseph H. Lewis, who made a lot of low-budget film noirs like Gun Crazy and The Big Combo, used that shot. He once told me he was simply looking for ways to avoid doing two re-lights in one day, and then he realized that it was great because the person who is looking away is denying what the person is throwing on them.

Hartley: Lewis was right. There’s a terrific dynamic when someone refuses to look at someone else. What is going to add tension between two people besides what’s just written in the script? Nothing bores me more than a two-shot of two profiles looking at each other. It’s even boring to do two singles and cut back and forth. I’m very interested in the choreography of the actors in the shot, and being aware of how the shot will start out as one thing and end up as another. That often leads me into a way of thinking about a scene, even if I don’t move the camera or the actors don’t move. It leads me to create strategies like the one you’re describing. In Henry Fool I often asked myself, what would cinema verite be like if you weren’t allowed to move the camera?

Filmmaker: There’s a lot of Woody Allen shots like that.

Hartley: Yeah, Woody Allen actually does a lot of really beautiful work that way. But I contained it a little bit more. I wanted a kind of lively feeling of almost uncontrolled activity in front of the camera. I would find an image that I thought was appropriate and beautiful to some degree and just start choreographing the actors through it. I told Michael Spiller, my cameraman, "Let’s not worry about the fact that somebody goes out and they’re standing there, and their head is above [the frame]. We’ll look for the conventions of appropriate framing so that the audience will know that we’re not just fucking around, but a lot of things will be, like, atonal."

Filmmaker: How do you keep your eye alert, not fall into your own conventions – what some critics have called "Hartleyisms"?

Hartley: Well, I’ve never understood what "Hartleyisms" are. One very practical thing that is easy to talk about is that I really don’t want to ever build a set. I don’t want to do too much artwork on a pre-existing area. I found myself in Henry Fool really just finding places, getting to know those places and getting to know what intrigues me about those spaces. In Henry Fool we built the World of Donuts but it would have been more fun if we hadn’t. If the actors were in a real delicatessen, even if I wrote it in the script that there were 45 kids milling about by the counter, and [the owners] said, "Look you can only fit 10 people. I mean that’s the challenge. Try to make the actual place work, make it integral to the film – that’s what I find myself doing more and more. Use less equipment, use a smaller crew. Don’t adjust the reality around me so much, but take the time to find the right highly designed image in the actual [location]. I want to keep putting myself in the position of greater vulnerability so that my instincts, sensibilities, and skills are always challenged. Because at that moment, that moment in that room, you are really paying attention, you are really looking hard. It feels like there’s a lot at stake. And you think more clearly. You think more creatively.

Filmmaker: A number of people who like your films somehow assume that they are purely cerebral, that they’re more intellectually derived.

Hartley: You should never forget that a lot of people don’t think that movies are actually made by people. A certain kind of moviegoer resents being reminded [of that fact], resents feeling the artifice. I don’t see the point of disguising the artifice of art. It all grows out of practical creative ambition. Desire is the first thing – you want to see a certain thing, but you also want to see it a certain way. You want to create beauty out of things that are around. That’s the way I want to do it now, simply from things that are around.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →