THE NUMBERS GAME

With his first feature,  , director Darren Aronofsky, along with producer Eric Watson and star Sean Gullette, creates a startlingly original no-budget sci-fi thriller that manages to combine number theory with cabal hermeneutics, taking home festival awards and a profitable distribution deal in the process. Scott Macaulay unearths the equation of the filmmakers’ success.

, director Darren Aronofsky, along with producer Eric Watson and star Sean Gullette, creates a startlingly original no-budget sci-fi thriller that manages to combine number theory with cabal hermeneutics, taking home festival awards and a profitable distribution deal in the process. Scott Macaulay unearths the equation of the filmmakers’ success.

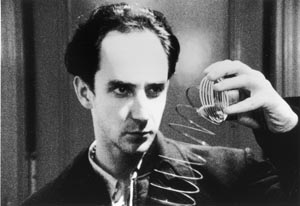

Sean Gullette as Max Cohen in![]()

Photo: Matthew Libatique

Film is a collaborative artform but few first-time films profit so richly from communal filmmaking energy as ![]() , Darren Aronofsky’s arresting no-budget thriller. Produced and co-scripted by Eric Watson and starring Sean Gullette (who also co-wrote), the film was very much a a group effort over a lengthy two-year development and production process. Finished in time for Sundance ’98, the film won Aronofsky the Director’s Award at Sundance, a lucrative distribution deal from Artisan Entertainment, and a seven-figure payday on his next movie.

, Darren Aronofsky’s arresting no-budget thriller. Produced and co-scripted by Eric Watson and starring Sean Gullette (who also co-wrote), the film was very much a a group effort over a lengthy two-year development and production process. Finished in time for Sundance ’98, the film won Aronofsky the Director’s Award at Sundance, a lucrative distribution deal from Artisan Entertainment, and a seven-figure payday on his next movie.

While![]() has probably launched a handful of careers, more importantly, it’s kept alive the notion of viable and challenging no-budget production. (

has probably launched a handful of careers, more importantly, it’s kept alive the notion of viable and challenging no-budget production. (![]() ’s complete budget – up to the 35mm print that was screened at Sundance – is included here.) No-budget films are harder and harder to make these days. Crews are burnt out, state labor departments are cracking down on unpaid labor, and few filmmakers have the visual imagination to make their no-budget movies anything more than static slacker pics. The 16mm, black-and-white

’s complete budget – up to the 35mm print that was screened at Sundance – is included here.) No-budget films are harder and harder to make these days. Crews are burnt out, state labor departments are cracking down on unpaid labor, and few filmmakers have the visual imagination to make their no-budget movies anything more than static slacker pics. The 16mm, black-and-white![]() , however, is different. Replacing stunts with ideas, action sequences with imagistic montages, and special effects with an eerie reimagining of New York City,

, however, is different. Replacing stunts with ideas, action sequences with imagistic montages, and special effects with an eerie reimagining of New York City,![]() shows that the no-budget filmmaking can be both intellectually provocative and entertaining.

shows that the no-budget filmmaking can be both intellectually provocative and entertaining.

Filmmaker: In terms of guessing this film’s inspirations, it seems like you jumped a decade past the standard ‘70s movie influences of your generation to ‘60s paranoia films like Mirage and Point Blank.

Darren Aronofsky: Actually, Polanski’s got a lot of responsibility here. But a big influence on![]() was Tokyo Fist by Tsukamoto, the guy who did Tetsuo. He just went out and, in a low-tech way, created his own style. We were like, "He can do it, so we’re going to do it." The problem with Tsukamoto is that he’s not a strong narrative filmmaker. I love stories, and I started

was Tokyo Fist by Tsukamoto, the guy who did Tetsuo. He just went out and, in a low-tech way, created his own style. We were like, "He can do it, so we’re going to do it." The problem with Tsukamoto is that he’s not a strong narrative filmmaker. I love stories, and I started![]() with the idea of taking these interesting ways to shoot things and applying them to a normal narrative film.

with the idea of taking these interesting ways to shoot things and applying them to a normal narrative film.

Filmmaker: So you’re more story oriented than some of your contemporaries?

Aronofsky: I’m a story junky. Titanic – you know exactly what’s going to happen the whole time, yet emotionally it works on millions of people. And I think that’s not a problem. The problem is how to take stories and push the limits of film grammar and structure. Pulp Fiction was structured great, but it still had very traditional setups and payoffs. Film is like humor – setup, setup, setup, punchline. And that’s how you tell stories. You set them up and then pay them off.

Filmmaker: How did you guys all meet and then decide to make this movie?

Eric Watson: Darren and I came up to the Independent Feature Film Market [IFFM] three years ago and saw that there was a film community here in New York and that this was the place to make movies.

Filmmaker: What film did you come to the IFFM with?

Watson: Nothing. As a vacation.

Filmmaker: You went to the IFFM as a vacation?!

Watson: I had never been to New York before, and I had the most amazing eight days of my life. I moved out here two months later. The goal was to make a movie in two years, which is what we did. The whole filmmaking process for us [involved] blind ignorance. We would meet with people and say, "We are making this movie no matter what!" We just had to throw away those fears, and it was a little easier to do that here in New York. I think it also comes down to finding a crew, finding people like Sean. I work in commercial production to make a living, and I got lucky in that Scott Vogel, my co-producer, had been working in the production community here for six or seven years. So we were able to get a free lighting package. As for crew, if you believe in something you can find other people to believe in it. They’re not going to be the most A-list crew in the world, but they are people who are in some ways more motivated because they believe in the script and the people that are making it.

|

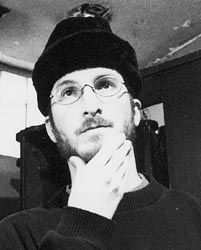

| Director Darren Aronofsky Photo: Sue Johnson. |

Filmmaker: So why do you think it didn’t get done?

Aronofsky: It was much more ambitious than![]() as far as the budget, but I think the real reason was at that time I didn’t have partners. I was going out there alone. I think one of the biggest things I learned from

as far as the budget, but I think the real reason was at that time I didn’t have partners. I was going out there alone. I think one of the biggest things I learned from![]() is that partners can help you get it done. Whenever you are slacking, those guys slap you around, and whenever they’re slacking you can slap them around.

is that partners can help you get it done. Whenever you are slacking, those guys slap you around, and whenever they’re slacking you can slap them around.

Filmmaker: It seems like every filmmaker who is working independently has that first-time coming-of-age movie.

Aronofsky: I did too, I just couldn’t get it made!

Filmmaker: How much footage did you shoot on![]() ?

?

Watson: Fifty-three thousand feet of 16mm. Twenty-three hours. That was over a 28-day period as well.

Filmmaker: Where was the principle apartment?

Watson: We built it. Scott’s father has a lighting warehouse out in Bushwick, which is a pretty grim area. Warehouses, stray dogs, police cars driving around. We found this back room there, gutted it, and built the set. It was cold. It wasn’t the best situation in the world, but at the same time, for no money, it allowed us to have a set.

Sean Gullette: It became our sound stage. We developed this very dense homemade supercomputer which was scavenged from dozens and dozens of old 286s and IBM machines.

Filmmaker: How did you go about developing the story and central character?

Gullette: I think this film’s merits come very much out of the choices that were made about how to develop it. And one was to develop the character and the script simultaneously. Darren and I had an initial idea for a character – sort of an aesthetic and a psychic state. And we built Max up from that.

Aronofsky: I had this one [script idea] called Chip in the Head. Sean was the only actor I knew in New York, and I had an image of him standing in front of a mirror with an exacto blade digging into his brain and pulling out a microchip. So I talked to Sean and he said, "O.k., I’ll give you eight months to workshop this." And in eight months it basically came together. I don’t know how. All these different themes just sort of evolved.

Filmmaker: What about the various philosophies in the movie, like the idea of the spiral unifying theory of nature? Where did that idea come from?

Aronofsky: Personal observation.

Filmmaker: I’m sure that idea is out there and people follow it.

Aronofsky: Oh, yeah. I started to realize it afterwards. I was in a vintage bookstore last week, and there was a self-published book about a guy who was applying the golden mean and the golden spiral to the stock market. And I was like, "That’s my movie!" It was just a book published in 1991 by some crackpot. And then there’s a theorist named Dan Winters. How did we find Dan Winters?

Watson: On the Internet.

Aronofsky: He has this really great website with all these ideas about shape and humanity. He sent me his books, and it turned out that he had taken the Jewish characters and shown how geometrically the letters were tied into mathematical formulas. We used Hebrew in a totally different way, but he was deconstructing the alphabet, actually saying that the geometry of the letters had cosmic meaning. Which made me start to think that filmmaking itself is, in many ways, like paranoia. They tell you in all the screenwriting courses that everything should come down to that one character or one theme. And that’s exactly how paranoids think. They look at the world and think that everything is related to them. And as filmmakers we are constantly trying to construct universes where everything ties into one character.

Watson: And that idea fits this character extremely well. One of the big metaphysical polarities of the film is the idea of a scientist who is desperately driven to find order in this world, and that also becomes an emotional problem for him.

|

| Sean Guillette and Shenkman in |

Filmmaker: One thing I really liked about the movie was the way that the mathematical ideas advanced the narrative in a very economical way.![]() is structured as a quest movie. But early in the film you have a scene where the older guy tells Max that he may find this spiral pattern he’s looking for but it’s not going to be significant because anyone can find this pattern anywhere. It’s a coincidence of nature. At this point, the whole value of the quest itself is called into question, and the narrative stakes are raised.

is structured as a quest movie. But early in the film you have a scene where the older guy tells Max that he may find this spiral pattern he’s looking for but it’s not going to be significant because anyone can find this pattern anywhere. It’s a coincidence of nature. At this point, the whole value of the quest itself is called into question, and the narrative stakes are raised.

Aronofsky: What I think you’re saying is that we were able to pull off an ambiguity – is this really happening or not?

Filmmaker: Yes, but there’s a sense of narrative gamesmanship going on. There are lots of movies about deranged guys going mad in their apartments. A lot of these films buy into their protagonists too much. The audience loses sympathy for them. But with this scene I’m referring to, you throw in a dash of skepticism that makes the story more unpredictable.

Aronofsky: If we had said, "This is totally the truth. What you are watching is reality," I think the audience would have gone, "No way."

Filmmaker: That scene not only ups the narrative stakes – we wonder if the film will find a satisfactory end to the protagonist’s quest – but it also makes the quest more universal. Max’s search is really the search we all undertake, the search for meaning in our lives.

Watson: It doesn’t have to be math, it could be politics, anything. The important thing is how that draws the character forward through the narrative. It’s narrative skill that makes [the quest] be more than a Maguffin.

Aronofsky: Early on, we wondered, how is an audience going to like Max Cohen? He is cold and emotionally shut down. We had some faith in Sean’s charisma, but then we also gave the character some cool traits. That’s where the character of the little girl comes in. When, in the beginning of the film, Max solves the math problem for the little girl, (a) it convinces the audience that this guy is a math genius in a sort of comedic way, and (b) you can see that while he’s shut off and shut down, at least he’s not extremely rude to the girl. The audience can sense that he’s trying to reach out; he just can’t.

Filmmaker: What inspired these sort of non-narrative montages that punctuate the film, like the shots of trees swaying in the breeze?

Aronofsky: The trees were ultimately Sean’s idea, actually. I sent Sean up to the country to work on diary entries for the character. He had an epiphany there, came back, and said, "There has to be a scene where the character goes to Central Park and he stares out at the trees." Eric and I were like, "Not a chance." I had another symbol for nature I wanted to use, the Chinatown symbol. But eventually I figured out a way to shoot the trees that for me would be interesting, and that was to change the frames per second. At first Max is staring at the trees, and we’re shooting at 18 frames per second, so it’s slightly sped up. And then when Max is in really bad shape, we shoot at 12 frames per second. And then, at the end of the movie, we shoot at normal speed and instead of pushing in on the trees, we pull out. Max is seeing the world. That’s the idea, the metaphor.

Any sort of gimmick or in-camera effect that we used had to be meaningful, and the meaning ultimately had to come from Max’s point of view, because the whole film is a subjective movie. Every shot comes out of Max’s head. The slow-motion or sped-up stuff actually has a story reason and pushes the narrative forward. You know, if you can figure out what your [camera] tricks are, what your shots are, and you just focus on those, then you control your palette and stylize your project a lot more.

Filmmaker: What are some other stylistic devises you used?

Aronofsky: The idea was to make a purely subjective film; Max is in every frame of the film. Sometimes it’s his POV and you don’t see a body part, but the shot is always connected to him. So we did all types of different things, like we only shot over Max’s shoulder, and we never shot over another character’s shoulder because that would bring us on to that other character’s point of view. When we shot the other people we shot them slightly off POV, while when we shot Max, we shot him from a side angle to create a sense of objectivity; we were studying Sean and were with him as opposed to other characters. We shot an extreme amount of closeup POVs so the audience would have a sense of how a mathematician thinks. This subjectivity also inspired the editing, inspired the music.

Filmmaker: So a lot of decisions that might seem like post-production choices, like the use of slow motion or accelerated action, were actually made very early on.

Aronofsky: Yeah. Probably one of my skills as a director is that I’m also an editor. I knew how scenes were going to go together. So coverage was very basic. I rarely shot masters. I only shot masters if I was really pushed for time, and whenever I did that, I suffered. But I really hate masters for this type of film. I mean, Jim Jarmusch’s [films are] all about masters, and it’s beautiful the way he shoots them. But everything in![]() is about Max. A master shot doesn’t exist – it’s objective, a stage show for the camera. There’s never a shot in

is about Max. A master shot doesn’t exist – it’s objective, a stage show for the camera. There’s never a shot in![]() where Max enters a scene. Instead, Max is there and the scene has begun. And we made scene transitions by using extreme close-ups so that we could go from a shot of Max’s face to some type of extreme close-up, some type of montage that happens in that scene, and then an extreme close-up that happens in the next scene, and then the next scene begins.

where Max enters a scene. Instead, Max is there and the scene has begun. And we made scene transitions by using extreme close-ups so that we could go from a shot of Max’s face to some type of extreme close-up, some type of montage that happens in that scene, and then an extreme close-up that happens in the next scene, and then the next scene begins.

Filmmaker: Was the voiceover part of the original script?

Aronofsky: I always wanted a voice-over because I felt voiceover would help us care about the character. Max is calm, he’s got a nice voice, and the audience gets sucked in. But I only wanted to use it so that it would help expand the film. And I think it did, because we let the audience get into how Max’s mind works. But you learn after you make your first film that you don’t need to explain as much as you think you do. Images and little bits of scenes give you enough.

Filmmaker:![]() is also a great New York movie. It presents a real multicultural view of the city at a time when the physical landscape of midtown at least is getting more homogenized.

is also a great New York movie. It presents a real multicultural view of the city at a time when the physical landscape of midtown at least is getting more homogenized.

Aronofsky: That was definitely a conscious choice. I grew up in a very multicultural Brooklyn. And that’s the way I view New York in some ways.

Filmmaker: The ethnicities of the supporting cast – the African-American Wall Street woman, the Indian next-door neighbor, the people in Chinatown – also displace the protagonist. He’s the minority in this world.

Aronofsky: Well, that’s Chinatown. We chose Chinatown partly because of [Mayor Rudolph] Guiliani. He’s cleaned up New York so that it’s an unrecognizable sort of science fiction world. It’s Demolition Man sci-fi as opposed to Road Warrior, which is aesthetically more pleasing to me.

Filmmaker: I would think you’d like some of what Guiliani is doing, like the surveillance cameras in Washington Square Park!

Aronofsky: Giuliani is doing some fucked up things, so I don’t know if I’m going to live here for long.

Filmmaker: Did you steal all your subway shots?

Watson: Yeah, we couldn’t afford that $18,000.

Aronofsky: We just hung out on the platform from 10 PM to 6 AM for about a week.

Filmmaker: What’s with the brain? The pulsating brain on the subway platform was the one thing shown in the film that could only be the product of the protagonist’s psychosis. Aronofsky: The brain is open to your interpretation. What do you think it is?

Filmmaker: I don’t know. It seemed like a little homage to Eraserhead.

Watson: Film is fantasy.

Aronofsky: It’s your brain, Scott.

Watson: It’s Guiliani’s brain.

Sidebar: ![]() 's budget and breakdown.

's budget and breakdown.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →