IN PRINT

Night of the Hunter & My First Movie

The Night of the Hunter

By Simon Callo

Indiana University Press, $10.95 paperback, 96 pages

François Truffaut queasily likened The Night of the Hunter, actor Charles Laughton’s 1955 directorial debut, to a "horrifying news item retold by small children." Quoted in Simon Callow’s new British Film Institute monograph on the film, Truffaut goes on to offer a bit of middlebrow advice proving that the confluence of film criticism and box-office commentary is not solely a turn-of-the-century phenomenon: "Screenplays such as this are not the way to launch your career as a Hollywood director. The film runs counter to the rules of commercialism … it will probably be Laughton’s single experience as a director."

Indeed, Laughton’s use of an Expressionist, theatrical mise en scene and flashes of burlesque humor to adapt David Grubbs’s best-selling blend of Southern Gothic and Grimms’s fairy tales resulted in newspaper attacks on the film’s "arty" direction. The reviews weren’t all bad but enough were; depressed and unfinanceable as a director, Laughton soon abandoned his planned adaptation of Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead. Lack of critical support on its release coupled with Laughton’s retreat from film directing resulted in The Night of the Hunter’s peripatetic status within the Great Films canon. It’s the kind of glorious one-off that falls to the footnotes of film histories, even if it’s also the sort of masterpiece that other directors spend a career working up to.

Today the film’s influence remains scattershot. Although the LOVE/HATE tattoos on star Robert Mitchum’s hands are quoted in Do the Right Thing and Scorsese’s Cape Fear, the influence of Laughton’s Manichean children’s odyssey only occasionally pops up in films, such as Bernard Rose’s Paperhouse and, especially, the work of David Lynch in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. The film’s greatest influence may have been in the theater; The Night of the Hunter’s classic nighttime river ride sequence – with frogs and lizards foregrounded by d.p. Stanley Cortez’s diopter shots while a small boat containing the two fleeing children edges downstream in the background, all as Mitchum’s sinisterly sung spirituals echo in the air – presages the visual tableaus of the experimental theater and opera director Robert Wilson.

In fact, Truffaut’s peculiar description of the film may hold the key to both its enduring fascination for cineastes as well as its lack of mainstream appeal. With Disney, and later Spielberg, popularizing a totally secular and socialized children’s fable, The Night of the Hunter’s serial murders, attack on religious fundamentalism and depiction of a child’s discovery of grace wrests something challenging from the genre.

Callow, a British actor who previously penned a biography of Laughton, dutifully runs through the film’s colorful production and pre-production in this latest volume in the BFI series. He describes Laughton’s attempts to find a visual correlate to Grubbs’s free-flowing prose and the director’s struggle to get a workable script from alcoholic screenwriter James Agee. (After turning in a 350-page draft, his script was largely rewritten by Laughton.) In a too-short section on the film’s shooting, Callow details Cortez’s studio lensing of some of the film’s most striking set pieces and, in general terms, Laughton’s success at working with his various collaborators. If Callow’s somewhat stuffy book can be said to have a thesis, then this latter point is it. (First sentence: "Of all the collaborative arts, film is the most complex, owing the most to the greatest number of people, a river into which many streams flow." Uh, okay.) And although one might come away from this text desiring a hipper take on the film, such is the value of The Night of the Hunter that Callow’s last line really does say it all: "Laughton’s failure to make another film is a serious loss to the history of the movies, but his one masterpiece continues to inspire those who share his sense of the expressive possibilities of the medium." – Scott Macaulay

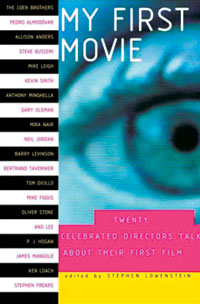

My First Movie: Twenty Celebrated Directors Talk About Their First Film

My First Movie: Twenty Celebrated Directors Talk About Their First Film

Edited by Stephen Lowenstein

Pantheon Books, $27.50, hardcover, 458 pages

Mike Nichols famously remarked that directing a movie is like making love: you always wonder how the other guy does it. There’s endless theory, but the actual moment-to-moment job is some-thing each individual has to learn. Although a book of stories about failed first films might be more fascinating, there’s probably less of an audience for it than My First Movie, a practical and sharp anthology of interviews filed with lots of stories with happy beginnings from the likes of Pedro Almodovar, the Coen brothers, Bertrand Tavernier, Mike Leigh, Stephen Frears, Steve Buscemi, Neil Jordan and Ang Lee. Virtually all of the interviews, conducted by editor Stephen Lowenstein, have the weight of experience and the heft of anecdotal specificity. (One director asked Clint Eastwood for his best advice. Eastwood replied, "Get more sleep than your actors.")

After years of writing and planning, Buscemi still had endless crises with his producer and the bond company. He muses, "It amazes me that any film gets made, especially an independent, because the bottom can drop out at any moment That’s the thing I didn’t realize as an actor. It is a miracle that we all show up on the first day."

Frears, out of his depth answering questions on the first day of shooting Gumshoe, reflects back, "At the time, I thought, Christ, I didn’t know my job description included being able to tell you things like this! And I didn’t give a fuck, because in one sense, it doesn’t matter. Now I’ve learnt to say, ‘You decide, and I’ll tell you if you’ve made the wrong decision.’ " After 30 years of filmmaking, he says, "It often seems to me that the director is the most redundant person on a set."

"Let people do their jobs," Buscemi says he learned. "It started to sink in that it was [the crew’s] job to be very anal about everything and pay great attention to detail and talk amongst themselves." On set with John Carpenter, he noted how quickly Carpenter made up his mind. "I said, ‘That’s pretty good, John.’ And he goes, ‘Always give them an answer. You can change your mind later, but you’ve got to give them an answer.’ " Terser still, "You have to hire people who know their jobs. It’s their job to figure out what you want."

The interviews are endlessly readable, and each of the directors, who also include Neil Jordan, Anthony Minghella and James Mangold, have the benefit of several other films under their belt for additional perspective. Some directors relied on published accounts to inspire their maiden effort – Kevin Smith read a piece in Filmmaker on the budgeting of The Living End, El Mariachi and Laws of Gravity – but most of the compelling catalogue of false starts and second thoughts deals with the hard-won experience of shooting a first feature.

The book is full of little practical things that even someone working on a set is unlikely to have the leisure or privilege to observe. A tip from Tavernier on that first day, after the throwing up is done: "If you’re unsure of yourself, ask for a very complicated camera movement. The time they’re setting it up will give you time to put together a few ideas." Not only did he do that, but the move worked for the film.

A theater director who was a mentor of Figgis’s told him, "The ideal plot is like a Swiss clock. If you take out one more cog it ceases to work and if you add one more it won’t work either. So your rule always should be, minimal writing that doesn’t abandon logic and at the same time calls on all those things that thrill you when you see other films."

P. J. Hogan had a neat trick for Muriel’s Wedding: "What I like to do is photograph all my locations, make a big book so I can see the location for scene seven right before the location for scene eight, and then I became aware that some scenes were open and some scenes were very closed. Some scenes in the location were light and some scenes were very dark, and generally what I knew was that when Muriel came to Sydney I wanted a sense of freedom for her."

Coverage has to be learned, Figgis observes. "You can be a wonderful doctor, but unless you learn certain surgical techniques, you may kill a lot of people." Mangold’s teacher, Gill Dennis, offered this theorem of screenwriting: "You should write a movie as if you were describing a finished film to a blind person."

My First Movie is a worthy attempt at preventing discerning first-timers from stumbling into the larger pieces of furniture on their first day on a film set. – Ray Pride

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →