COMMITTED

On the eve of two theatrical releases – the sci-fi romance Happy Accidents and the insane-asylum shocker Session 9 – writer/director Brad Anderson speaks with Travis Crawford about maintaining a career as an independent filmmaker

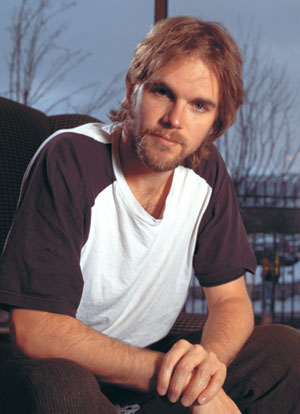

Brad Anderson photographed by Richard Kern

When last year saw the release of two films from director Steven Soderbergh, many expressed admiration for his ability to helm two worthwhile projects in such a short period, but indie filmmaker Brad Anderson is about to pull off a distribution feat that almost makes Soderbergh look slothful by comparison. Anderson has directed, edited and co-written two features that are being released within two weeks of each other. Happy Accidents is a light romantic comedy/time-travel fantasy (picture Henry Jaglom remaking Somewhere in Time) being distributed by the Independent Film Channel’s theatrical division, and Session 9 – his best film by a considerable margin – is a grim, unnerving horror movie from USA Films.

From a production standpoint, however, this is actually not as remarkable as it initially appears. Although Session 9 was completed only recently, Happy Accidents has been finished for some time now and has been languishing in distribution limbo since playing to mixed notices at its Sundance premiere last year. Nevertheless, Anderson’s achievement remains notable primarily for the insight it offers into the director’s versatility and his ability to personalize projects that seem to be essentially genre exercises – in this case, two projects and two genres that couldn’t be more dissimilar.

Session 9 is a striking entry in a loosely defined new American movement of independent horror films that use the framework of the genre to establish a tone of dread and unease that is sustained through an exploration of psychological collapse rather than gory mayhem. It could fit somewhere between titles like Lost Highway and The Blair Witch Project, as well as new indies such as Michael Walker’s Chasing Sleep and Larry Fessenden’s Wendigo.

A radical departure from Anderson’s previous buoyant work, Session 9 is a thriller about the gradual mental disintegration of a five-man asbestos-removal crew working for a week in an abandoned insane asylum. David Caruso and Scottish actor Peter Mullan command the contracting team (which includes co-writer Stephen Gevedon). Much of the film’s tension is derived from dissecting the implosion of these two characters’ friendship, as each grows more and more uncertain of the other man’s grasp on reality.

|

| Session 9: Stephen Gevedon |

But the real star of the film is the asylum itself: Anderson shot Session 9 in the actual deteriorating, vacated Danvers State Mental Hospital in Massachusetts, providing the project with the creepiest horror-movie location since The Shining’s Overlook Hotel. Session 9 is the first Anderson film to display a strong visual aesthetic. Although the choice of setting undeniably contributes to this, Anderson’s decision to shoot the film with the new Sony CineAlta 24P HD (high-definition) video camera and then matte the image to a widescreen ratio also lends the film a singularly stylish presence. Although it does have its flaws – certain gaps in narrative logic become more pronounced during the film’s final moments, for example – Session 9 is a genuinely suspenseful and eerie concoction.

Comparisons between Anderson and Soderbergh can be instructive for reasons other than simple volume of output, as Anderson himself observes. Although Anderson has yet to achieve mainstream success, he, like Soderbergh, has spent his early career as a quiet, unassuming craftsman of low-key character studies and revisionist genre efforts. Unfortunately, Anderson has not had the fortune of Soderbergh’s initial sex, lies and videotape triumph – when sex, lies distributor Miramax released Anderson’s Next Stop Wonderland (1998), the film failed to find an audience. (His 1996 debut, The Darien Gap, also acquired little attention following its Sundance premiere.) Yet his ability to continue finding finance for his low- and medium-budgeted features makes for an encouraging case study. Session 9 is probably too bleak to afford Anderson his first hit, but it clearly bodes well for his progression.

FILMMAKER: Looking at your previous work, I don’t think many people would have expected you to tackle a horror film. What prompted the change in direction?

BRAD ANDERSON: There’s this notion that filmmakers are like a one-trick pony – once they have established their genres, that’s it. But it’s all about reinventing yourself, and my own interests go far beyond romantic comedies. I’ve always had a real interest in horror, but I just didn’t get a chance to do one until I made a few movies. Doing a horror movie is a challenge, but it’s also like a comedy in some respects – it’s a finely tuned structure. I also thought that there has been a lack of good horror movies these past several years, as opposed to "terror" movies, which just deliver jolts. A lot of the movies that seem to be erroneously categorized as horror now aren’t horror at all – they’re glib teen comedy thrillers, and they’re not scary. But I did want to break away from the romantic comedy genre and try something different.

FILMMAKER: Session 9 came together very quickly. You came up with the idea early last year and were shooting in the fall. Was it difficult to obtain backing for the project?

|

| Session 9: Peter Mullan |

FILMMAKER: What was it like shooting with the 24P HD video camera?

ANDERSON: We got that camera just as it started hitting the market, and we might be one of the first films hitting theaters that was shot on 24P. The movie was originally conceived as a no-budget DV project, but when USA came on board, we knew we still didn’t want to shoot it on 35mm, but we needed something in between. When you go up to this place, you see all these creepy little details that we didn’t want to lose, and we felt that with hi-def, we could get all those. And the 24P thing gives us the advantage of a filmic look, and because it was a new camera, it felt like we were pioneering a little bit. We were really happy with the look. When you’re shooting 24P, you get to work on set with this incredible hi-def color monitor, not some little video tap. The working dynamic with the d.p., Uta Briesewitz, is different because the director is really seeing exactly what they’re going to get. The advantage of that is the director can be as much a part of the visualization of the shot as the d.p., but the disadvantage is that everyone gathers around the monitor, which slows things down.

FILMMAKER: Session 9 is heavily geared around establishing an ominous tone, not hammering the audience with cheap shocks, and I imagine that sustaining that approach in the editing is not always easy. I heard that you had some conflicts with USA Films regarding input gathered at test screenings.

ANDERSON: It wasn’t conflicts with USA as much as it was conflicts with the audiences, balancing what they wanted with what I wanted. I’m not a big test-screening advocate. I think they can really water down the director’s vision. We were dealing with audiences who wanted Scream or I Know What You Did Last Summer, and they didn’t expect this movie that didn’t go for glib one-liners and that had a totally bleak ending. We did make some changes: there were confusing elements in the story that we tried to clear up a bit, and there was a different ending that we cut because it was almost too bleak. We had this assaultive, brutal ending with Peter Mullan’s character being killed by this ex-patient, but we determined that it was better to keep things more ambiguous; it’s unusual that the test screenings resulted in an ending that has less closure. USA was pretty accommodating, and they didn’t demand anything. Having been through that process before with Miramax, I know that it can be really ugly, but with USA, it wasn’t like anyone felt like they were getting stepped over. You’re right about the tonal thing – all along, we were intent on capturing a feeling, and those movies are a hard sell in this business. I wasn’t totally into The Blair Witch Project, but I appreciated that it did go for that tone, and you don’t see that much.

|

| Happy Accidents: Marisa Tomei |

FILMMAKER: Happy Accidents premiered at Sundance last year, but is only just now being released. What were the circumstances surrounding the delay?

ANDERSON: IFC produced the film, and at the time, they weren’t distributing theatrically. At Sundance we got picked up by Paramount Classics, and they gave us the whole "We love the movie" thing when we were in negotiations. And then several weeks later, they used some minor TV-rights clause as their "out" of the contract, and they dropped the movie. They never really gave us an explanation, but presumably someone higher up didn’t like the movie and had second thoughts. It was kind of a shock because we thought we were going to have the film distributed last summer by Paramount, which is a cool company – or so we thought. In the end, they didn’t have the courage of their convictions. And this business is so fickle, that after that happened, other companies that had been interested began to get cold feet, and it was like a curse had been cast on the movie. Ultimately, IFC started up their own theatrical distribution arm, and they are releasing the movie that they financed, that was their baby. It opens your eyes to the way this business works: this company that had made this allegedly gracious offer backed out without a single comment. It was baffling, but I hold no grudges.

FILMMAKER: You’ve managed to remain prolific as a filmmaker, despite some career obstacles – not only the distribution dilemmas with Happy Accidents, but also your problems with Miramax – they didn’t handle Next Stop Wonderland particularly well, and they also cancelled the remake of When the Cat’s Away that you had been slated to direct. Do these setbacks ever trouble you, and do you feel any pressure to "break through" to more widespread success?

ANDERSON: Ultimately, the question is, what is the definition of "breaking through"? Is it about making movies that go bonkers at the box office, or making really good films, or mainstream Hollywood movies, or films that target a specific demographic? I look at the careers of some filmmakers, and they’re successful, but they’re making complete dreck. They haven’t fulfilled their potential. And then there are those filmmakers who just continue to make good, cool little films. Someone like Soderbergh has an interesting career. As a filmmaker, I look upon his career and really respect him, even if I don’t love all his movies. He continued to do very distinctive movies, and then went on to do bigger movies that are still his thing; he’s successful but hasn’t gone mainstream, and he’s also prolific. And my hope as a filmmaker is to create a diverse body of work. Not everyone is going to get every film because they’re coming from different places. And if one of them ends up being a bigger movie, then that’s great.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →