ROMANCE NOVEL

Returning to his native Colombia with high-definition video camera in hand, Barbet Schroeder shoots Our Lady of the Assassins, a violent Spanish language tale of a writer searching for impossible love. Ray Pride interviews the director.

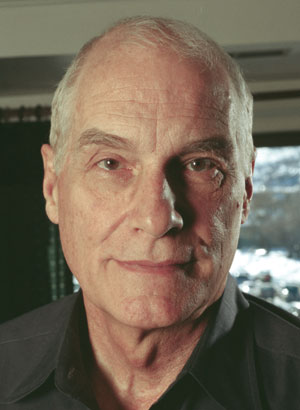

Barbet Schroeder photographed by Richard Kern

Whatever can be said about Sundance 2001, the festival’s first press screening furnished a serene gem, veteran producer-director Barbet Schroeder’s Our Lady of the Assassins. A startlingly mature work, in all the best senses of the word, this tale of impossible love set against the backdrop of teenage contract killers in Medellín, Colombia, is a model of magical miserabilism.

But Schroeder, whose musical, cosmopolitan accent reveals everywhere he’s been in his long career, though nowhere in particular, has made an almost 40-year career of producing contrarian work. His company Les Films du Losange co-produced a number of Eric Rohmer’s films as well as Jacques Rivette’s 1974 classic funhouse of narrative, Celine and Julie Go Boating. Most of his work as a director is available on video, including his 1969 debut, More, a counterculture-critical LSD tale with a Pink Floyd score. His documentaries include 1974’s Idi Amin Dada, a peculiar and intimate look at the notoriously inhumane Nigerian dictator, with a score by Amin. Among his better-known fiction features are his 1987 adaptation of Charles Bukowski’s novel, Barfly, 1990’s award-winning Reversal of Fortune, and the progressively less successful studio pictures Single White Female, Kiss of Death, Before and After and Desperate Measures.

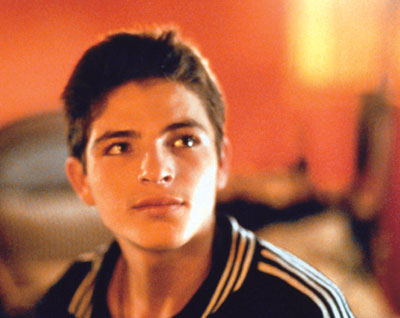

In Our Lady of the Assassins – based on Fernando Vallejo’s 1994 novel La Virgen de los Sicarios – a middle-aged writer, Fernando (Germán Jaramillo, intense and wry) returns to his home city after many years. He is startled by the near nihilism of daily life, its random shootings and absurd events. Meeting a teenage gangster, Alexis (Anderson Ballesteros, movie-star-striking though a nonactor), he begins an affair. Violence escalates. Fernando blasphemes, speaking in cynical poetry of what he sees around him. But his lover’s impulsive shootings fascinate him: "All these killings are encouraging my own self-destructive urges." The horror of living where life is unlivable is a grandiose spectacle, yet the film is as cool and collected as its characters. "We should indulge every vice to prove we’re alive. Virtue is for the dead," Fernando tosses off.

Our Lady of the Assassins, Schroeder’s first foreign-language film in 16 years, is an outstanding portrait of how writers talk, live, and invent the greatness of their romantic others. Ray Pride talked to the 59-year-old Schroeder following the screening of his film at the Sundance Film Festival.

|

| Anderson Ballesteros and Germán Jaramillo |

FILMMAKER: Tell me about Vallejo’s approach to the script versus the novel.

BARBET SCHROEDER: He made a big effort, both in the movie and in the script, to use slang words in a way that could be understood by every Spanish-speaking person in the world. The novel is a big monologue. There is only the writer talking all the time. The boy has no voice in the novel, no dialogue. In the book, the point of view of the boy is never seen, so you have a little bit of a distance. In the movie, it becomes a story of two people, an impossible love story. So that’s the magic of cinema – suddenly you have two people, two or three.

FILMMAKER: Is there an irony in the novel that we are reading a monologue by a writer who is not actually writing? The film gives us the impression that he no longer writes.

SCHROEDER: Yes. Let’s say that he doesn’t take himself seriously as a writer. He’s a great, great writer, and he knows it, but he’s not pompous about his writing. Actually, he’s very similar to Bukowski in that respect. They’re both writers who are very nihilistic, very funny, very irreverent, and whatever they write is in the first person. It’s always them or a persona that is very close to them, that could be them. Of course, one is homosexual and the other is heterosexual, but that’s a small difference in their sensibilities.

FILMMAKER: There are different writer types. Some are very quiet, and they shut themselves up in their rooms. Some writers talk; others, if they talk too much, their writing suffers. And then there are those who write and talk. What’s wonderful about the character of Fernando is that the poetry and the gallows humor when he speaks is filled with exasperation and weariness, but it’s so well spoken. There are moments in which, as a character, he’s being sardonic about the craziness he sees around him, but the voice is steeped in a writerly sensibility.

SCHROEDER: Absolutely. I like to show a writerly sensibility in daily life – not the writer as he is writing, with big classical music and some pompous classical-masterpiece type of sensibility. Of course, the fact that Vallejo writes some of the most beautiful Spanish written today according to some of the greatest critics is why I did the movie in Spanish. For me, it would have been ludicrous to have people speaking English when you have this beautiful language. This is a movie that was done out of love of language.

FILMMAKER: It’s also fascinating to watch a writer enoble his own experience. Writers tend to have problems with relationships because they’re determined to elevate those around them.

SCHROEDER: Yes. Absolutely.

FILMMAKER: The story’s surface could be reduced to cliché: there’s violence around Fernando; he’s sad; he likes boys; somebody’s going to die. But there are all these other layers and resonances. Was that all there for you in the novel?

SCHROEDER: Yes, it was.

FILMMAKER: The story turns when a second boy, Wilmar (Juan David Restrepo), who seems much like Alexis, appears. He starts out being like a rough-trade version of Alexis –

SCHROEDER: Of course!

FILMMAKER: He’s very blocky, his chin is stockier, but in the scene where Fernando waits for him to awake, wanting desperately to know something, holding the gun on the boy, you give him a moment of vulnerability – the beauty shot, looking soft, full-lipped.

SCHROEDER: You know, I played very much on that idea of doubling from Vertigo, one of the great movies.

FILMMAKER: You even have a poster behind him when they meet with the word doble, or double, on it, and there’s also the reversible jacket one of the boys has. It’s a plot point, a cool gimmick, for him to be able to escape a shooting on the street, but it’s also a playful way to show that doubling.

SCHROEDER: Exactly. The movie is very, very constructed.

FILMMAKER: These are characters who are inventing their own absurd world, an absurd world of intense despair. But they are also making a world just for themselves. You’ve dealt, again and again, with characters who do that from Idi Amin to Claus von Bulow to Bukowski. Is that reading in too much?

SCHROEDER: No, but what really interested me here is to have a love story, and in that love story to have the point of view of the boy on the writer and the writer on the boy – this exchange of point-of-views, with the camera trying to see the man as the boy sees him and the boy as the man sees him – all that in an impossible love story that is beautiful precisely because it is impossible. And then I tried to duplicate this beautiful love story [a second time in the film] in a pathetic way with Wilmar, who doesn’t have the same magic in his personality but who is, formally, better-looking, in a way. But for me, of course, the first boy, Alexis, is ten times more magical.

|

| Anderson Ballesteros. |

FILMMAKER: How’s your Spanish? You lived in Colombia until what age?

SCHROEDER: Eleven. I guess I had to relearn it. My Spanish is not so good, but I have a feel for it. I was able to read the whole work by Vallejo in Spanish – that’s what started me [on this film]. I was so enthused, enthusia – you see, the English I don’t speak good either [laughs]. I don’t speak any language properly except the movies! I was so enthused, you say? I had a dictionary, but very often I did not stop to translate some of the words. The music of the writing was so beautiful, so extraordinary, that I was [always working] to reach the end of the next phrase. I kind of understood the words and didn’t need the details because the music was so beautiful anyway.

FILMMAKER: Did any of Fernando’s reveries about the past of Medellín match yours? It’s so black-humor funny when he witnesses the shooting in front of the house and he’s mad: "They got blood on my childhood home!"

SCHROEDER: Yes. I have some rough memories of my childhood. The violencia started when I was a child. I was seven or eight when the riots in Bogota took place. It was the bloodiest thing, unbelievable. I have extremely violent memories; it was very scary, a total breakdown of the law. There was blood everywhere. There were hundreds of dead people from the riots. Not dead from the police but from people killing one another in the streets.

FILMMAKER: The tone of Our Lady of the Assassins is fascinating. It’s serene but not resigned. You have shoot-outs, for instance, but the film itself doesn’t get excited. That seems to reflect how Fernando, on his return, is quickly anesthetized to the violence. Producing an American studio picture, you’d be bombarded with the note "When does he express his misgivings?"

SCHROEDER: I know, I know! That was obviously the thing I was working on. That is why I wound up shooting the violence like that. I wanted the audience to identify with him and the violence in the same way he was experiencing it and not to go into too many gory details. That’s not what you see when you are walking in the street and you see someone get killed like that.

FILMMAKER: You have one shot that I was wondering how long you were going to hold without cutting: Fernando and Alexis are on the balcony, the city splayed out below them, and Fernando is explaining why he reveres Maria Callas. And the boy, who doesn’t hear that at all, says it sounds like someone is being strangled, but his eyes are brimming when he comprehends Fernando’s transport, the light bringing out his eyes.

SCHROEDER: Yes, exactly. That’s also the star treatment of the boy. I treated those boys, who were taken from the street, as if they were movie stars. And because they had the magical quality of movie stars, this magnetic thing that is like a transfiguration [happens] when they are on tape. Suddenly they are much more beautiful than they are in life.

FILMMAKER: They also lack the baggage we would bring to stars we’ve seen before.

SCHROEDER: Yes, but at the same time, you can find good actors, you can find people who are very natural, but to find people who make you dream, who have this extra thing, that was hard – especially because they had to be good-looking. I was like a casting agent of the ’50s! I was searching for good-looking people who had the magic of movie stars. That, I guarantee you, even in a town of four million inhabitants like Medellín, is not easy to do overnight.

FILMMAKER: You’ve supported the careers of a number of filmmakers over the years as a producer, particularly Eric Rohmer. Superficially, he’s just words-words-words, but there are many layers and nuances there. There are those who argue that cinema isn’t words! It seems there’s such a paucity of great language and poetry in dialogue nowadays. Is a film like this a reaction?

SCHROEDER: No, it’s just that that’s what I like. I like to put myself at the service of a great text. I like to be in love with every word that is uttered in my movies. I think that’s how you get great performances: you get a great writer to give music to the words.

FILMMAKER: Did producing the work of others make you more adventurous as a director?

SCHROEDER: No. [Producing] was just a prolongation of being a film buff. It was just part of my love of movies. Now I have no time. I’ve got to concentrate on my own stuff. what!

FILMMAKER: Was the HD camera large?

SCHROEDER: It’s quite big. It’s like a BetaCam. You can’t hide it; it’s not a thing you hold in the palm of your hand. The shots are it – it’s really moviemaking. Everybody thinks, Oh, it’s done in video, so they think of the Dogme stuff. [This film] is lit, directed, the colors are controlled. There is not one color in the frame that was not planned, and so on.

FILMMAKER: There seem to be too many films originating on video in which the filmmaker is trying to approximate the look of a film originated on 35mm instead of a look that accommodates video’s different appearance.

SCHROEDER: I was not trying to have a film look. I was trying to explore whatever new possibilities this new thing had. Actually, I discovered that [digital video] opens up a lot of possibilities of manipulating the image in a cheap way. But the most important contribution to this new way of filming is the use of multiple cameras – something Renoir discovered with The Testament of Dr. Cordelier [in 1959]. If I had to do a movie in 35mm now, I cannot imagine doing it without two or more cameras. For example, we have a scene and we film it with two cameras, one on you and one on me. Then in the middle, suddenly, I go away, I go out, slam the door and meet a beautiful girl in the hallway, and there is another camera or two outside. Then when we hit the good take, the actor would be carrying the good take into the next scene. This would be very exciting. Somebody like Cassavetes having that would have gone crazy! I can’t imagine what he could have achieved.

FILMMAKER: When you look at a potential project, particularly a studio project, if you come to a dead end, what is usually the problem?

SCHROEDER: For me the casting is really something crucial. If I can’t get the ideal cast for a movie, I prefer not to start the movie. After all, it’s one or two years of my life, and I’ve got to believe completely in what I’m doing. If I start on the wrong foot with the casting, it’s a mistake to do it. But that can be wrong also. I try to remember Johnny Guitar by Nicholas Ray. That film is a masterpiece, a fantastic thing. But Ray was not at all happy with Joan Crawford. He was desperate. [He felt] it was the biggest mistake of casting – and he was wrong!

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →