THE LAST TYCOON

Nanette Burstein and Brett Morgen’s adaptation of the memoirs of Robert Evans, The Kid Stays in the Picture, stretches the conventional definition of non-fiction filmmaking. Adam Pincus talks with the directors about the film’s spectacular special effects – and its even more spectacular subject.

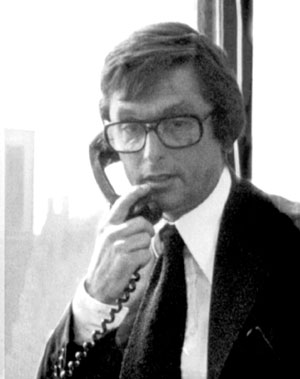

Robert Evans overlooking New York's Central Park.

Brett Morgen and Nanette Burstein arrived at this year’s Cannes Film Festival with their film The Kid Stays in the Picture in the company of a slew of American non-fiction filmmakers. It was a mixed bunch that included veteran Direct Cinema practitioners Frederick Wiseman and D.A. Pennebaker, first-time documentary filmmaker Rosanna Arquette and populist provocateur Michael Moore, whose Bowling for Columbine represented the first documentary film in the official competition in over 40 years.

Morgen and Burstein, were nominated for an Academy Award in 2000 for their cinéma vérité boxing doc On the Ropes. As filmmakers, they hail from the direct cinema tradition of Wiseman and Pennebaker. Both, in fact, began their filmmaking careers working for Barbara Kopple, who had worked with Albert and David Maysles. But The Kid Stays in the Picture, their new cinematic memoir of Hollywood-heavy Robert Evans, is the antithesis of a film like Showman, the Maysles brothers’ classic 1963 portrait of movie producer Joseph Levine. One could argue, in fact, that it bears little resemblance to non-fiction filmmaking at all.

Robert Evans’s memoir, on which the film was based, was first published in 1994, joining other canonical works of the genre like Julia Phillips’s You’ll Never Eat Lunch in This Town Again and Lynda R. Obst’s Hello, He Lied: And Other Truths from the Hollywood Trenches. The book charts Evans’s delirious, turbulent career, and it is rife with bluster, backlot lore and epic self-aggrandizement, undercut by the author’s singular brand of egomaniacal humility.

The book is a brilliant read, but it was the book-on-tape of The Kid that made it an instant cult classic. While Evans’s prose has a vivid snap, it is his voice – a rich, New York-inflected mumble – that conveys the essence of the man, his undeniable charisma and over-the-top worldview.

Certainly there are a number of ready models for a film version of The Kid, most of which can be found on cable television. And Evans’s life does follow fairly neatly the durable arc of VH1’s Behind the Music. But with financing from USA Films, and theatrical distribution a given, Morgen and Burstein knew that the devices of the small-screen celebrity saga were at once too familiar and too small for their outsized subject. Instead, they constructed a film with lavish 35mm cinematography, manipulated imagery, and Evans’s own voiceover narration.

The ultimate result is a film that seems to have multiple authors – and agendas. There’s Evans’s own persuasive myth-making, an outlandish story corroborated by the staggering display of lush black-and-white stills, newspaper accounts and his undeniable legacy: a credit crawl of the masterpieces of ’70s studio filmmaking that includes The Godfather, Chinatown and Rosemary’s Baby. And then there’s the cultural implications of the film’s producing credits – in addition to Morgen and Burstein, the film was produced by Vanity Fair editor Graydon Carter. And finally, there is the often sneaky messaging of the filmmakers themselves, who at turns comment and collude in the creation of "Robert Evans: the Movie."

Still, for the attentive viewer, some nagging questions remain.

|

| Robert Evans and Norma Shearer. |

Filmmaker: How is this movie different, ultimately, from an E! True Hollywood Story? [Long, awkward silence.]

Brett Morgen: I don’t even think we should justify that question. It’s so not an E! True Hollywood Story.

Nanette Burstein: Well, the readers don’t know that. People think of celebrity profiles, and they think of E! True Hollywood Story or A&E Biography. And in fact, when this idea first came out, that’s what people were saying. And it’s not, because...

Morgen: The Kid Stays in the Picture is a film that from the get-go fully immerses itself in the mind and body of its subject. And [the film] is unlike pretty much any non-fiction film before it, in the sense that this is a movie that is told entirely by one man speaking off-screen for 93 minutes, which is probably the worst premise for a theatrical film one can come up with. In fact, when we were first approached to do this – and the studio agreed to do it – Nanette and I walked out of the meeting and said, "This is going to be the most fucked up, subversive studio film since Medium Cool."

Filmmaker: Your last film, On the Ropes, took a fairly traditional non-fiction filmmaking approach. It felt like it came straight out the direct cinema tradition. This one is pretty much the opposite, in the way you manipulate images, use Evans’s voiceover...

Burstein: We completely recreated the world you see, and made use of 3D images, cut things out and put them over backgrounds. It’s an image that’s created, so is it real or is it not real? How much has been distorted? This is like creating a ride in Disneyland.

Filmmaker: So, do you even consider it a non-fiction film?

Burstein: It’s not a non-fiction film. It’s one man’s perspective. But the thing is, this film makes no bones about it from the first image. It says, "There are three sides to every story: Your side, my side, and the truth. And no one is lying." We’re hearing one man’s version of his life. But, in a way, it’s more honest than most documentaries because every non-fiction film is totally subjective. They [just] pretend to be objective. We’re just coming out and saying what we are.

Morgen: The first shot of the film is a red velvet curtain. It represents the fact that everything you’re seeing is on a stage. It’s all theatrical. We’re acknowledging constantly through the entire film that what you are seeing is a distorted truth. Most documentaries – where they interview Person A, and then Person B has a completely different view – the viewer is led to think, "Wow, I’ve seen both sides. This must be an objective film." But we all know that the essence and nature of film is entirely subjective.

Filmmaker: Given that Evans narrates the film, this one is particularly so.

Morgen: Bob’s book on tape is hilarious; it’s a wonderful ride if you want to go on it. And we wanted to take the audience on that ride. We didn’t want to critique it. They can critique it if they want. They can sit there with their own judgments about Bob. Hey, at times maybe he buries himself, maybe he entertains you. What I truly hope [the film] does at the end of the day is call into question for the audience what a documentary truly is. When I see a movie like Fast, Cheap & Out of Control, that movie to me challenges my notions of what non-fiction is. You see a topiary gardener, at night, in a hurricane, shot on 35mm. Now, clearly a topiary gardener wouldn’t be out at night working on his sculptures in a hurricane. It’s a representation of the man’s internal landscape. And that is what The Kid Stays in the Picture really embraces.

Burstein: It’s funny, because our last film, On the Ropes is a cinéma vérité portrait. It presented the "Truth." But what was clear in the making of it was that we were showing very much our perspective of it. Here, we were creating our own universe. What’s interesting is, if you look at one of the fathers of documentary, Robert Flaherty, who took real people but dressed them up, did complete reenactments, didn’t even portray the way their lifestyle was anymore, yet made some of the most celebrated...

Morgen: We can go through 10 of the great non-fiction films of the last 10 years – there’s nothing objective about any of them. Do they acknowledge it? No. They’re doing what the dominant cinema does, which is to present the illusion of truth.

Filmmaker: This feels more like a filmic adaptation of a literary work, a memoir. Or to be more precise, a book on tape.

Burstein: It’s a third-person autobiography.

Morgen: When we were making this film, we would constantly celebrate the fact that this movie is really going to challenge our traditional notions of non-fiction. What’s happening right now is, you have films like Dogtown and Z Boys, you have movies like The Kid Stays in the Picture, you have movies like Wild Man Blues, and they all co-exist under the same banner. And they’re totally different in every way, shape and form. But what unites them is the idea that they’re all based on someone’s subjective reality.

Filmmaker: The question in this case is, whose subjective reality? Typically in making a non-fiction film, a filmmaker imparts their point of view in how they shoot their subject, and in the editing process. The prism through which the audience experiences this "non-fiction" is the filmmaker’s perspective. But this film actually has a kind of double lens on it, because what you guys are making a film about is Evans’s own mythology of himself. A lot of the critical work has already been done – by him.

|

| Brett Morgen and Nanette Burstein. |

Morgen: I have to take issue with that. It’s not like we just allowed Bob to tell a story. Part of the subtext of the film has to do with what we talked about at the beginning: every image in the film is distorted. What Nanette and I thought when we made this film is, "Here’s a guy who got everything in his life based on his image, and when that image became tarnished, he lost it all." This is a guy who gets "discovered" because he looks like someone. He gets a job running Paramount because of a favorable article in The New York Times – without having ever spent a day as a producer working in a studio. He saves the studio by making a movie presentation for the board of directors. His lowest moment of his life is when his name is plastered all over the press in a scandal.

Burstein: We go out of our way to show that – from the excessive use of photography, the lushness. By making it seem like some enchanted, fairy-tale world, by making Bob’s house the main character. From the fact that there are newspaper headlines everywhere, and the fact that there are these 3D, distorted images. We are winking at the audience about the subtext the whole time. If you look at Bob’s book – it would take you 12 hours to read that book. Within that, we have constructed a story-line which presents our own perspective. That’s why we call it a third-person autobiography: because it’s our interpretation of Evans’s interpretation of himself.

Filmmaker: When you make a film with a consummate myth-maker like Robert Evans and you base it on his own memoir of his life, he’s obviously in some ways a co-author of it. How do you handle conflicts between his agenda and your own as filmmakers?

Morgen: Make no mistake about it: we had final cut on the film. Bob had no approval whatsoever.

Filmmaker: Did you fight with him about the cut?

Morgen: We fought with Bob endlessly. We told Bob that if he didn’t want to talk about something, we were going to figure out how to deal with it anyway. Let’s take the example of women. Bob, to his credit, does not like to kiss and tell. He does not like to boast about how many women he’s bedded. In fact, in his book, he doesn’t even talk about it. So we said, "Bob, you know we have to address the fact that you’re one of the great womanizers of the past 50 years." He said, "I not going to talk about it. It’s boastful." So we found these interviews with Bob where these reporters are saying to him, "You’re constantly seen with women. Is it really as good as it seems?" And Bob says, "I don’t go out with many women. I hardly even go out." Meanwhile, what we’re showing the audience is a rapid-fire montage – over 800 photographs in the course of a minute of Bob with various women.

|

| Robert Evans in The Sun Also Rises. |

Burstein: The other thing is, on the book-on-tape there is absolutely no mention of his drug bust, and the [Roy Radin] murder, and the scandal. And he didn’t want it in the movie. So in the second half of the movie, it was Brett’s voice doing Bob until a week before we screened at Sundance. Bob basically knew, if he didn’t do it, there wasn’t going to be a film. And we wrote all the voiceover, so it’s not like we were subject to Bob’s control.

Filmmaker: You wrote the voiceover? It doesn’t come from the book?

Morgen: No. That’s why I have an "Adapted by" screen credit on the film. We wrote things…

Burstein: Bob would change them.

Morgen: He would put them into his own words, or add his own thoughts. He would argue over the word "and." Petty arguments. We co-authored certain passages, we collaborated with him to put it in his voice, to find the words that he was comfortable with. Ultimately, every documentary film is a collaboration – even in a cinema vérité context – between the subjects and the filmmakers.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting that you worked with d.p. John Bailey on the film. He’s in many ways a quintessential Hollywood image-maker who has worked with everyone from Paul Schrader to Robert Redford. But he’s not an obvious choice to shoot a documentary.

Morgen: When I was 15 years old, I went to a school called Crossroads, in L.A., and I wrote a term paper called "The Films of John Bailey." I’ve always admired John’s films. He’s incredibly versatile. He has a sensuality to his work, and he always adapts himself to the subject matter. But we only had a $40,000 production budget and we were, "thinking there’s no way we can afford this guy." It turns out, John is a huge fan of non-fiction film, and he was a big fan of On the Ropes. He loved what we were trying to do with this film. He didn’t know if it would work, but he loved the idea of it. We wanted there to be an excess to the stuff we shot with John – similar to what De Palma did in Scarface, where the excessive use of the crane, the excessive use of the steadicam is a commentary on the Tony Montana character. We wanted our film to have that sensuality, we want it to have that excessiveness, that decadence and that emotion as well. As Douglas Sirk said, "Motion is emotion."

Filmmaker: What did he bring to The Kid Stays in the Picture?

Morgen: We came up with this idea of filming the house – it was the only stable force in his life over the last 30 years. We thought that Woodland [the house] represented Bob’s internal landscape, that when Bob is on top of the world, Woodland is this pristine place where the colors are hyper-saturated, just this Land of Oz.

Burstein: Kind of an enchanted garden.

Morgen: And when Bob’s life starts to crumble, the house begins to crumble. Literally, we go way over the top. Nanette and I threw 3,000 leaves all over Bob’s house to get this crane shot. There are no leaves in Hollywood!

Burstein: There were leaves in the pool, there were leaves all over the lawn. Everything has a blue tint to it. We completely constructed the visuals. We are not filming real life. In real life, although you have a lot of choices in what you choose to put [into a film], in the end you’re at the mercy of what your characters do on camera. Here, we can shoot anything. We completely constructed our photography, we constructed the images we used. Everything was just a canvas to play with.

Morgen: A blank canvas. We knew what the audio was, but we had 90 minutes of screen time to fill.

Filmmaker: The bulk of the screen time is taken up with still photographs, which could have been deadly. But the way you handled them – the 3D technique you’ve alluded to – feels very original and it’s a distinctly cinematic device.

Morgen: When Nanette and I started the film, we knew we were going to rely heavily on stills. And with USA Films in at the very beginning, we knew we were making a theatrical non-fiction film, and we knew we were going to have to do something different. We could not present stuff the way you’re used to seeing it on TV. We wanted everything to be sort of 3D – a fantasia non-fiction film – but we didn’t know how to do it. We hired an editor named Jun Diaz, who was the editor of American Movie and is also a commercial editor. Jun is a master of After Effects. We had never heard of the program before we met him. Jun really showed us that anything we could think of was possible, all in this very simplistic program that you can have on your home computer.

Filmmaker: It a pretty staggering volume of photos you had to work with.

Burstein: The first thing we did was go over to his house and there were photo albums and albums of newspaper clipping. It was like his whole life was leading up to this moment.

Morgen: I asked Bob once why he saved everything. He said, "From the time I was 15 years old, I knew I was leading an extraordinary life. I would finish my homework and go to the Copacabana, go out for a fling with Marlon Brando’s girlfriend at the top of the St. Moritz Hotel. I was in the gossip columns every day by the time I was 17 years old. I knew that no one would believe me if I didn’t save everything." Bob documented every facet of his life. When he was running Paramount, every time he went to a set, he would bring a studio photographer.

Burstein: Anyone who works in Hollywood is all about manufacturing image – and that’s what you do in life.

Morgen: What was interesting was that Bob didn’t have any home movies. We thought we were going to uncover a treasure chest of Super-8 and 16mm film, but we learned very quickly that Bob would never allow himself to be filmed because he couldn’t control it. If you’re in a still shot, you can control what’s happening – especially if you bring your own photographer. That said, we bought a lot of photographs that were not from Bob’s collection, particularly those from the ’80s. Bob did not save the pictures with drool coming down his mouth.

Filmmaker: You guys sound critical of non-fiction filmmaking. Is this film, in the end, a reaction against that tradition?

Morgen: Not at all. We’re an outgrowth of non-fiction film. We are very aware of the evolution and history of non-fiction. This film really challenges the whole notion. All we are doing is representing the postmodern aesthetic seeping into non-fiction film.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →