HEAVY METAL THERAPY

Documentarians Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky have made a career of being in the right place at the right time. So, when Metallica entered rock ’n’ roll counseling while they were making a promo piece on the band, the filmmakers knew that had another documentary epic on their hands. Andy Bailey reports on Metallica: Some Kind of Monster.

|

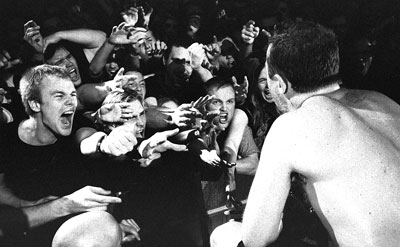

| Above and Below: Metallica’s James Hetfield and Lars Ulrich play to the crowd in Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky’s Metallica: Some Kind of Monster. PHOTOS: JOE BERLINGER. |

If cinema vérité entails shooting subject matter without a net, the filmmaking duo of Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky were in free fall mode with Metallica: Some Kind of Monster, a project that gestated over several years’ time and through various fits and starts before transmogrifying into one of the great rock ’n’ roll documentaries. Capturing America’s biggest heavy metal phenomenon in the throes of band member departures, fan disillusion, creative stagnancy, impromptu rehab sessions and, most precious of all, group therapy, it’s the mother of all rockumentaries, a work that goes so far behind the music that the modern rock ’n’ roll apparatus may never be viewed in the same light again.

Protégés of Albert and David Maysles, whose output included Gimme Shelter, Salesman and Grey Gardens, Berlinger and Sinofsky are no strangers to the vérité tradition. Their earlier works, including Brother’s Keeper and the two Paradise Lost films, delved deep into rural America, capturing very different subjects on trial for their lives. The latter films inspired the formation of the West Memphis Three organization, a public advocacy group that has fought to overturn the death sentence of Damien Echols, whose was convicted of murder despite questionable evidence. Berlinger and Sinofsky will return to Arkansas for a third installment of Paradise Lost, documenting Echols’s final plea for clemency.

The duo’s interest in Metallica stemmed from the band’s unwitting presence in the West Memphis Three investigation — Metallica’s music was as much on trial as the teenagers who listened to it, creating an atmosphere of persecution around a group that has sold millions of records and toured the world several times over since its inception in 1981. When Berlinger and Sinofsky sought musical rights for Metallica songs to use in Paradise Lost, the filmmakers were surprised to learn that the band were already fans of their work and were eager to help out. Licensing fees were waived, and “Sanitarium” spills over the opening credits of both films, a cri de coeur of adolescent ennui.

Some Kind of Monster originated in 1996 as a promotional film, a clips-driven retrospective of Metallica’s meteoric two decades in the business. But the filmmakers wanted deeper access to the band. After Berlinger’s disastrous experience directing Blair Witch 2: Book of Shadows in 2000, the duo contacted Metallica drummer Lars Ulrich, who invited them out to San Francisco to document the genesis of what would become the band’s 2003 St. Anger album. Ulrich indicated that a therapist had been hired by the band’s management to help them adjust to the imminent departure of bassist Jason Newsted. These sessions, in which the filmmakers’ cameras sat alongside the band, proved to be one of the great happy accidents of modern filmmaking.

|

Filmmaker: Some Kind of Monster already feels like it will go down as one of the great rock documentaries alongside Gimme Shelter and Don’t Look Back. But those docs captured musical acts at their apex, whereas this one gets Metallica at something of a low point. Is that what interested you in the project?

Joe Berlinger: First of all, I don’t necessarily agree that Metallica was on the decline, and I certainly don’t think that’s what attracted us. Of course we’re very flattered with the Gimme Shelter and Don’t Look Back part because we started [our careers working] with the Maysles brothers. Gimme Shelter was very much on our minds during the editorial phase of the film.

Bruce Sinofsky: Frankly, music films — concert-driven films — are a dime a dozen. I wish the Beatles had been very frank in 1969 during the making of Let It Be. I’ve joked around and said, “This is Let It Be with balls,” because, you know, it would have been amazing to see John and Paul and George really expressing what they were feeling about each other, the things that were eating away inside them and forcing them to break apart.

Berlinger: [Metallica] was a band in crisis, and that had added value. But what attracted Bruce and me to Metallica was that through our Paradise Lost dealings we had become friends with the band. We were amazed at how their onstage personas were very different from who they were as real people. We like to tear apart stereotypes in our films — Brother’s Keeper is all about stereotypes, Paradise Lost is too. As is this film. When we started it, we never imagined it would be a chronicle of a band nearly disintegrating and then coming back so strongly. The idea that Metallica was in therapy was certainly an attractive element.

|

Sinofsky: When James and Lars got into the fight and [the band] started slipping back into their old behaviors. James slammed that door and left for nine months. We had a feeling that if he came back and we were able to resume the access that we had without limitations, then there might be the potential for a great film. We assumed he’d be back in six weeks, like most rehab patients.

Filmmaker: How did the project change from a more conventional band-portrait film to what you wound up with?

Berlinger: Because of our interaction with Metallica over the years, the band had talked to us about doing a more clips-driven promotional thing. We wanted something a little more personal. We came out to San Francisco to document the making of the album and thought we’d only be there for a few months. When we saw that Metallica was in therapy, we used our relationship with the band to get our foot in that door, and we secretly hoped we could push it into something bigger. Lars and the guys agreed to let us film the therapy sessions, but we didn’t go in to film therapy as part of the promo film.

Sinofsky: The therapy was only supposed to be short-term. Phil Towle [the therapist hired by Q Prime, Metallica’s management firm] was brought in to deal with Jason’s leaving — and maybe even to talk Jason into staying with the band. But Jason thought the idea was weak and lame. We never expected we’d be there for two-and-a-half years.

Berlinger: Once these guys started talking, man, the floodgates of 20 years of macho aggression and not communicating with each other just opened up.

Sinofsky: In 2001, [undergoing] therapy was very common in America, but not for a band such as Metallica, which would be the last band on earth you’d think would allow cameras and therapists into their lives. And issues that James and Lars were dealing with were exactly the same things Joe and I had ignored for the previous two years. We weren’t discussing things that were building up. Listening to Phil, and listening to band members talk, it was clear to us that we had never addressed any of these issues [ourselves]. This film really saved our working relationship. We’re working better now than we have since the beginning. I think it allowed us to put things in perspective and go off and make other films. I really think we’ve reached a collaborative understanding that maybe we didn’t have in the past.

|

Berlinger: It was a very intense edit. Even though the film feels like it has a definite story, it wasn’t as obvious and literal a story as something like a murder trial. We filmed 400 hours of therapy alone. To pull out what’s relevant was really challenging. There was no obvious skeleton to hang everything on. One thing I miss about shooting on film is that every decision is very considered when it costs $300 for a camera roll. With tape, the tendency is to shoot everything and worry about it later. We worried about it later when we got into an editing room with 1,600 hours of footage.

Filmmaker: At some point this project was going to become a reality TV show.

Berlinger: As the film was unfolding and James went away for his nine-month absence, we decided to keep filming, and the record label agreed. When James decided to come back, that’s when the Osbournes’ show hit. When the music finally started coalescing, and the guys in Metallica started getting along and could set a realistic deadline for an album, Elektra agreed [that the footage] was special and decided to turn it into a reality show. At any other time in the history of reality shows I think we would have been more excited about [the idea]. At one point the label was talking about six hours on HBO culminating in a live concert. That was intriguing to us, but ultimately we didn’t think it was serving the material. And frankly, because this stuff was so raw and authentic, we felt that to try and compete with Ozzy wouldn’t be perceived in the right way. We told the band and its management that a film is treated with so much more importance, and that this was shaping up to be an important film. A reality show in this third or fourth year of the reality wave — it just wouldn’t be taken seriously.

Sinofsky: And people would have confused it with Survivor!

Filmmaker: But then Elektra was absorbed into Atlantic, people started losing their jobs, and Metallica stepped in to save the day.

Sinofsky: Q Prime, on a conference call with James and the band, asked if they wanted to buy Elektra out of the movie deal. Metallica said yeah. So basically the band wrote out a check for a million bucks and later paid every dime, to the tune of $4.3 million. And on top of that they’re going to spend another $2.5 million for the prints and advertising for the theatrical release.

Berlinger: That’s the beauty of this experience for Bruce and me as independent filmmakers. Even though it’s a paid-for film [by Metallica], it was the most trust we’ve ever been given by a subject. Not once did they tell us what not to shoot or what to take out. Then, when the film might have been turned into a reality TV show, the band stepped in and said, “We don’t want it to go down that road.” Elektra was gracious enough to allow Metallica to buy the property back. Their management supported us. Independent filmmakers don’t have this kind of experience very often.

Filmmaker: During your careers as filmmakers, the Paradise Lost story keeps coming back to haunt you. The USA Network is shooting a version of the story, Devil’s Knot, with you guys as executive producers, and HBO just greenlit Paradise Lost 3. Then there’s Alex Steyermark’s forthcoming West Memphis Three project, which you’re not involved with.

Berlinger: The USA Networks project is a dramatic film about the case, and actually we’re characters in it.

Sinofsky: I read the third draft. It was strange to read it because we’d been there already — we lived it. But I think the writer has captured the essence of the story in 90 minutes — something that took us two-and-a-half hours to tell in the original documentary.

|

| Directors Joe Berlinger and Bruce Sinofsky. PHOTO: HENNY GARFUNKEL. |

Sinofsky: Paradise Lost already had a life of its own in a sense that it created the West Memphis Three organization. I think if we hadn’t been above the radar with this film, Damien would have been put to death already.

Berlinger: Damien has told us he wouldn’t have gone for the appeal. He was so depressed after that [first trial]. If it wasn’t for the worldwide attention and the rock stars coming in — if it wasn’t for all that support, he would have allowed himself to be executed.

Sinofsky: Aside from the pain we went through making Paradise Lost, we’re gratified that the films had an impact. Who would have thought something like that would have been possible through celluloid? Even 12 years after its inception, it’s still something that robs you of your innocence.

Berlinger: It does rob you of your innocence. My wife was pregnant while we were filming the trial. During editing she gave birth. You’re sitting there late at night on the Steenbeck looking at hours of horrible autopsy footage — only a minute of gory footage made it into the film. But we had to wade through hours of it. You go home and pick up your new baby at midnight after having dealt with all that horrible footage. When you stare into the abyss of evil like that, it robs you of the innocence you have as a young father. And my second kid was born during Paradise Lost 2!

Filmmaker: Can you talk a little bit about what you learned under the Maysles’s tutelage?

Sinofsky: I was 19 when I went to work there in 1977, and I stayed with the Maysles for 14 years. The best thing that came out of it for me was working with Charlotte Zwerin, who co-directed Gimme Shelter, and David Maysles, who was my mentor. The next best thing was meeting Joe. One thing I learned from David involves the editing room. Every great film is going to look like a disaster during the [first] nine cuts. That tenth cut is when you really start to have something that makes sense. Films don’t just come together magically, and they often look like disasters until all of a sudden something clicks. Your 1,600 hours of footage finally boils down to two-and-a-half hours and looks and feels like a real movie.

Berlinger: I worked with the Maysles for six years, and one thing I learned from them was the old cliché that real life is infinitely more interesting than anything you could ever plan. Taking that a step further, real life can be shaped into a dramatic narrative movie that is worthy of theatrical release. That’s what Grey Gardens, Gimme Shelter and Salesman were all about. They were ahead of their time in terms of theatrical viability. The other thing I learned is that if you jump out a window in order to take these adventures, you have to believe there will be a mattress at the bottom. Having that confidence is so important. All of our films have sort of magically worked out. In Some Kind of Monster there were six or seven major crises along the way that could have shut the film down. As much as it took the band’s faith in us to keep filming while James was away, it took a lot of faith for us to stick with it because we couldn’t take on any other work. It ultimately took a year for James to come back, but we didn’t know whether it would be a week, a month or a year. And so we had to be in war footing, so to speak. We had to let so many other jobs go, and we’d kick ourselves, saying, “There’s another $40,000 we pissed away.” But it was worth it. The magic that the Maysles achieved, and what Bruce and I have learned from them, is that all the stuff that happens before the camera rolls, all the relationship building — that’s the directing. Once the cameras are rolling, we just have to let it happen. That’s so important in today’s world of contrived reality programming, where the whole situation is set up or faked. Reality TV is supposedly unscripted, but it’s totally directed, totally contrived. The vérité tradition pioneered by the Maysles and D.A. Pennebaker has sort of been lost.

Filmmaker: Do you believe we’re in a golden age of documentary filmmaking right now?

Berlinger: I think there is a golden age of audience receptivity to theatrically released documentaries, like Spellbound or My Architect. This was our goal way back with Brother’s Keeper, riffing off what Errol Morris had done with The Thin Blue Line. We wanted to make movies for a theatrical audience, movies as rich as any fiction film, which is also what the vérité guys of the ’60s wanted to do. There are two reasons [behind this resurgence] in my mind. Just like rock ’n’ roll was co-opted by the corporations, the independent film movement has been co-opted by Hollywood. Miramax now makes $50- and $60-million movies and all the so-called indies make $20- and $30-million movies. There was a time when an indie cost a couple of million of dollars and it grossed a couple of million and everyone considered it a big success. Now independent [fiction] movies have as much pressure for opening-weekend numbers as Hollywood movies. The theatrically released documentary has stepped in to fill that void. It has become the new art film, in my opinion. The second reason is reality television. People who have any kind of intellectual bent are so disgusted and horrified — as Bruce and I are — with reality TV. There’s a thirst for real quality nonfiction because the airwaves are loaded with all this contrived bullshit.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →