MULE VARIATIONS

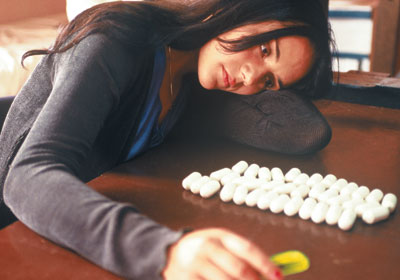

One of Filmmaker magazine’s “25 New Faces” of 2002, Joshua Marston travelled to Ecuador to make a new kind of American independent film, one that moves from the Latin American drug world to the streets of Queens, New York. Michael Koresky speaks with Marston about Maria Full of Grace and his character-based social cinema. Catalina Sandino Moreno in Joshua Marston’s Maria Full of Grace.

|

| Catalina Sandino Moreno in Joshua Marston’s Maria Full of Grace. PHOTOS: CHRISTOBAL CORRAL VEGA. © HBO FILMS/FINE LINE FEATURES. |

Could Joshua Marston’s Maria Full of Grace, the story of a pregnant 17-year-old Colombian girl who becomes a heroin-swallowing “mule” for a local dealer, be defining a new path for American independent film?

Largely in Spanish and shot in both Ecuador, Colombia and New York, the film, which won the Dramatic Audience Award at the Sundance Film Festival and the Best Actress Award at the Berlin Film Festival, is a warmly humanistic portrait of a solitary life in crisis, a life lived within the shadow of the U.S.’s economic and cultural might. And while this tale of an underprivileged drug runner who winds up stranded in Queens avoids polemicism at every turn, it remains an undeniably rich political statement. Like the early work of Roberto Rossellini, Marston’s debut feature universalizes its character’s plight by uniting the social, the personal and the political and then lightly overlaying a sense of the divine. And like the best of Ken Loach, it has a narrative urgency and a ragged, lived-in awareness of today’s stifling political systems. But ultimately, by dramatizing the contradictions and connections between personal choice and political reality and the tenuous codependence between the Northern and Southern hemispheres, it tells a new kind of American story with real subtlety and honesty.

Produced by HBO Films and Paul Mezey, Maria Full of Grace opens July 16 from Fine Line Features.

|

| Catalina Sandino Moreno and Yenny Paola Vega in Maria Full of Grace. |

Filmmaker: I feel like you’re doing things in this film — socially, politically — that we haven’t really seen much of in American cinema since the ’70s. Do you feel like there’s been something missing from American cinema right now?

Joshua Marston: I do feel that American films, and particularly American independent filmmaking, is often internal, solipsistic and too much concerned with the filmmaker’s own self-therapy. For me, the most interesting thing about being a filmmaker is that it’s an excuse to go out into the world and open myself up to other people’s stories. I’ve been inspired by the British and Brazilian schools of realistic cinema, and originally got into filmmaking through photography. I lived two years on and off in Paris, spent a year in Prague and several months in East Asia, Japan and Vietnam and did a lot of street photography. I ultimately got frustrated with photography, though, because I would come back with rolls and rolls of photographs, and each time I would show someone a photograph I would want to tell the story behind them. [The photos] were too “thin” for me — I wanted something thicker.

|

Marston: I’m not one of those people who knew from the age of three that they wanted to be a filmmaker. After college, I took a year off and taught high school in Prague, and then went to grad school for political science. I was going to get a Ph.D. but opted out with my master’s and went to film school at NYU. After I got out, I was making a living as an Avid editor on schlock TV, editing shows I would never watch. But it’s lucrative and you learn something. While I was doing that, I got the idea for the film, spent a year working on the script, traveled and did more research. I had showed it to producers, who said things like, “Couldn’t they all speak English?” or “Couldn’t Maria have a nanny that taught her English and they could practice their English?” I had someone else who wanted to get either Penélope Cruz or Jennifer Lopez for Maria. They just didn’t get what I wanted to do. My roommate’s boyfriend ran into Paul Mezey [the film’s producer], a former fellow student who had mixed the sound on a student film of mine, on a train, and struck up a conversation. Bless his heart, he said, “My girlfriend’s roommate has a script you might want to read.” So I sent it to Paul, and he read it in a week. Paul took it to HBO; HBO told Paul to just make it. In Spanish. With a first-time filmmaker. With an unknown cast. I think I owe my first-born child to HBO.

Filmmaker: I felt like there was something of Ken Loach in the film. I was wondering if you were conscious of any particular filmmakers while you were making this film.

Marston: I was very consciously influenced by Ken Loach, as well as Mike Leigh. And I have also watched Rossellini and Babenco and Walter Salles. But Loach would be the biggest. When I saw Ladybird Ladybird, it blew me away. I had to go back to the movie theater the next day and watch it again to see how he did it. So startling. My favorite film ever is Raining Stones. Ken Loach’s films are very influential for me because they have a social and political context and they’re making a commentary upon the world, but also because they’re doing so in a way where the filmmaking is subservient to the drama of the story and the power of the characters. It’s not about cinematic pyrotechnics.

Filmmaker: I felt this film was in many ways a corrective to drug films like Traffic and Midnight Express. Your film forgoes histrionics and is much more emotional and direct and personal.

Marston: Ironically, I first tried to write a script about the drug war. The first draft attempted to put out all this information I had gleaned about the drug trade. But I quickly realized that that [approach] was about ideology and polemics and not powerful filmmaking. I reread the first draft and realized that I had to approach [the subject] from a very different angle. I was then intent on it being “political” by virtue of the fact that it’s a character piece told from a point of view not commonly used. Drugs are illegal, there are drug “mules,” and it is affecting poor people’s lives in this horrific way. The story is not told from the point of view of a police officer or a drug agent or a sexy and powerful gun-toting drug trafficker; it’s a worm’s eye view of someone who lives through this experience.

|

| Catalina Sandino Moreno in Maria Full of Grace. |

Marston: We cast for three months — open calls in New York and New Jersey, in the Colombian communities in New York and also in Miami. For Maria, we saw 800 girls and maybe a handful that were possibly okay. You always have this fantasy that the right person is going to walk through the door, magically be the character, and it’ll be love at first sight. That wasn’t happening, so we decided to push back the shoot. And the very next morning a tape came from Colombia, another set of auditions, and Catalina was the first person on the tape. And within 30 seconds I knew it was her. It was instant. She has tremendous instincts. She had never acted for screen but for five years had studied theater on the weekends and done student theater projects.

Filmmaker: The film is very earthy and realist, but it also has a vibrancy. What was your relationship like with your d.p., Jim Denault?

Marston: We had a language in common walking into it by virtue of the films we both liked and because he had shot [Jim McKay’s] Our Song. We were talking about shooting in Colombia and he had just shot in Cambodia [on Matt Dillon’s City of Ghosts], which is not a safe country either. He understood working with a small crew and a small enough footprint so that you could incorporate the world around you and have it register onscreen. A lot of the films I like were shot in 16mm and blown up to 35mm, and we were in this odd position in which the producer and d.p. were arguing against the director in favor of 35mm. We did some tests and went ahead with 35mm, but I was concerned about maintaining an organic quality, an immediacy. So we shot handheld to maybe compensate for the tight grain and potentially slick quality of 35mm.

Filmmaker: What was the process of making a bilingual film?

|

| Writer-director Joshua Marston. Photo: HENNY GARFUNKEL. |

Filmmaker: What were the major logistical differences between shooting in Queens and in a foreign country?

Marston: We shot 20 days in South America — in Ecuador and a second unit in Colombia — and 20 in New York. I think shooting in South America was more exciting for me just because it wasn’t my own neighborhood or country — my eyes were so much wider and alive during the shooting of the first half [of the movie]. From a logistical point of view, I felt like I had more leeway, more rehearsal days and more human resources in Ecuador. Coming to New York meant working with [IATSE], working with SAG, keeping to a strict 12-hour day, shooting only Monday to Friday. A scene that didn’t make it into the film took place in a park where the idea was to see Latin families and immigrant families on a Sunday barbecuing and playing soccer and having a community. But it was difficult to capture [that scene in New York] because we couldn’t shoot on a Sunday.

Filmmaker: A viewer unaccustomed to this subject matter probably wonders how desperate your protagonist’s situation truly is before making this horrible decision. It’s difficult to sympathize with her at times. Are you trying to create a conflict within the audience?

|

Filmmaker: If you see yourself as a political filmmaker, what can we expect from you in the future?

Marston: I’m working on a script right now about a family in Tennessee having to reevaluate their lives as our society goes through what I think is a larger sea shift as we move to another stage of capitalism. I’m interested in what happens to people when they’re laid off. People talk about moving from a manufacturing economy within the U.S. to a service economy and [sending] manufacturing jobs overseas, but that’s rupturing people’s lives.

Filmmaker: When was it that you knew you had achieved what you had set out to do with this film?

Marston: One day our second editor, Lee Percy, had a question about the ending. He wasn’t sure whether it’s clear why Maria makes the choice she does at the end of the film. And it really plagued me. Then one day I expressed this concern to a Colombian woman helping with the casting, and she looked at me like I’m crazy and said, “Are you kidding? It’s so clear to me.” And she tells me what it was like within the first couple weeks of being in the U.S., standing on a street corner, using a pay phone to call Colombia for her grandmother’s birthday; what it was like to get her first paycheck and send money home. And basically I took these anecdotes and put them into a scene. It really was straight out of her mouth. Then, when we went to shoot the scene in the Colombian section of Jackson Heights, I walk out into the hallway and there’s this Colombian man of about 60 standing there, listening to the dialogue through the doorway. He said, “These stories are so true. This feeling you’re capturing is something I’ve felt for so many years living here. I can’t believe you’re actually putting it onscreen. I’ve never seen it in a movie before.”

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →