SUGAR DADDIES

With his feathered fedora and long white limo, the black pimp has loomed large in the American cultural imagination. But the reality, as the Hughes brothers demonstrate in their first documentary, American Pimp, can be both stranger and harsher than our fantasies. Karen Voss learns more.

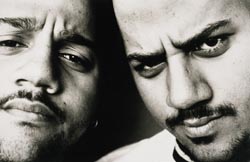

Director/Producer Albert Hughes and Pimp "Rosebud" in American Pimp. Photo: D. Stevens

American Pimp, the first documentary project by filmmakers Albert and Allen Hughes, puts a troubling spell on you. Opening with fireworks and a stream of "squares" (doughy whites who attempt to define the word "pimp"), the project launches its examination of working and retired pimps across the country within a larger acute critique of Americana. As the documentary snakes through the pimps’ urban underworld economy, the Hughes brothers’ signature bombast evident in Menace II Society and Dead Presidents gets redirected towards exposing the nuanced psychology and cultural mystique of the Black pimp.

Framed by archival footage, blaxploitation clips, and an intoxicating soundtrack, pimps hold forth about the details of their enterprise. Unsurprisingly, a lot of what they say is revolting as hell, but American Pimp energizes many other registers. Showcasing the pimp as historical, cultural, and media product, the Hughes brothers give us a glimpse of a particularly lurid form of capitalism while reminding us of America’s long-standing fascination with both sex and money.

The documentary, then, works its own kind of seduction. With nods to Iceberg Slim’s 1969 novel Pimp, which exposed the mechanics and complex hustles key to the trade (complete with a glossary of pimping terms), American Pimp likewise documents a subculture. Everyday exotica ranges from the surprising (most pimps maintain a pristine abstinence from drinking, drugs, and tricks) to the flamboyant (this is one dizzying style milieu) to the sickening (the aberrant pimp-ho psychological dynamic) and back to the bizarre (one pimp claims Revlon bought his beautiful fingernails because all he did was "peel money and touch bitches all day long"). But it is the pursuit of money, not sex, that structures the world of pimps, and ultimately, American Pimp is fairly chaste. When the white proprietor of Nevada’s Bunny Ranch fondles an employee on camera, it’s in stark contrast to the comparatively detached, poetic charisma of the Black pimp who asserts, "I do not buy dreams, I sell them." This is not to say that the pimps come across admirably, but in terms of industry and pluck they represent some inverted version of what America admires most.

|

| Left to Right: Allen and Albert Hughes. Photo: Matt Gunther |

Allen Hughes: We always wanted to do something on pimps, but we never thought we’d want to do a documentary.

Albert Hughes: We thought it was going to be a movie based on Iceberg Slim’s novel, Pimp.

Filmmaker: Is there a relationship between that novel and your film?

Albert: We were going to do an adaptation of the novel, and then, before we had the opportunity to grab the rights, some clown in town acquired the rights because he knew we wanted to do it. This guy tried to lure us in, and, to make a long story short, he said one thing and did another, and now it’s somewhere else.

Filmmaker: Did you have a guiding structure in mind for the documentary when you were interviewing the pimps or did your ideas change during shooting?

Albert: At first we came into this whole thing like, hey, hey, it’s got to be flamboyant, it’s got to be this style. We were going to do split screens, etc., until it hit us right between the eyes halfway through shooting that we’ve got to pull back.

Allen: We started to get with these guys and started piecing the scenes together and we realized this is not about us – it’s not like a [fiction] movie.

Albert: Although there are no real rules for constructing a documentary, I think we will get slashed by mainstream documentary filmmakers. Their films fall into more of a slower-paced, dramatic, pull-at-your-heart kind of thing. They like to do that to win the awards. This is not in that vein. So we know we’re not going to be a favorite as far as winning awards, but we’re not in it for that. We were in it for totally exploring this lifestyle and – this was our mistake at first – making the filmmaking parallel the flamboyance of the pimp lifestyle, even overshadow it. It didn’t work at first. The pimps were too flamboyant.

Filmmaker: The film is very smooth viewing, especially with the soundtrack.

Allen: That’s the one thing I think somebody out there will hit us for – the music in the movie. I’m not insecure about it because it’s justified in my head. But that’s one thing we both learned about this documentary. You grow up and you think of documentaries as, "Hey, these are the facts. This is what they are." They’re not like movies. And that’s such bullshit. You learn when making a documentary that any time there’s one man or woman behind the camera it’s going to be slanted somehow, some way – it’s only a matter of degree. And when you put music in... I started to get nervous in the beginning because once you put music in with subject matter like this you’re glorifying it. In most documentaries, if you have a serial killer you’re not going to play James Brown while he’s saying, "I killed this motherfucker."

Filmmaker: It’s not entirely inconceivable.

Allen: Yeah, but we’ve got wall to wall music. I looked at it like this: the music you hear in the movie is the music these pimps grew up with. This is the stuff they pimped to, basically. A lot of them would make suggestions about music. It isn’t like we took Led Zeppelin and threw it in there. Somebody suggested, "Why don’t you put more of an eclectic selection of music in the movie? Put in some rock, put in some blues." Those guys don’t listen to that shit.

Albert: Plus, we’re pretty much purists when it comes to our soundtracks. We don’t want it to become too bubble-gum pop.

Allen: "Papa was a Rolling Stone" and "Who’s that Lady" are in the film and those are thorns in our sides because they’re so recognizable.

Filmmaker: So, if the soundtrack functions as a level of documentary, do the blaxploitation film clips and other ’70s cultural items function the same way? I wondered if part of your motivation for making this film had something to do with being so familiar with the cultural constructions of the pimp character that you wanted to see how that imagery compared to the actual street.

Allen: Yeah, it ties in to the idea of people always having an opinion about a pimp but never having actually sat down with one. We know [that people get those images] from the movies and media. And then you get with [the pimps], and you find out that there are some exactly like the stereotypes and a lot that are contrary and some in the middle. It’s all across the board.

Filmmaker: Did you end up cutting any of the pimps because they were too offensive?

Allen: There was one guy we wanted to cut out because he was talking too loud, yelling, "Ahhh, motherfucker" everywhere.

Albert: We did the interview, and we realized, this is so ridiculous. I pulled the film out and exposed it.

Filmmaker: Because he so was lewd?

Albert: No, he was going off on my brother. He was drunk and trying to show off. Then, when we got to the editing room months later a new editor, Doug Pray, came on and said he heard the dialogue from that [exposed] roll. He said, "We need to pull this stuff." I told him, "I don’t think I have it..."

Allen: You know what he said, though? What you find when you’re doing a documentary is that the people you hate are sometimes the ones who end up saving your film, and the ones who you love are the ones who don’t do shit. Doug said, "You’ve got to pull this up." So we listen to the interview months later and we were like, oh my god! Once your emotions aren’t involved anymore, [the interview] becomes humorous, shocking or whatever it really is. And it turns out [Albert] didn’t really throw it away.

Albert: We shot three rolls, and I threw away one.

Allen: [That pimp] is the extreme case, the one you love to hate.

Filmmaker: What else got left out of the movie?

Allen: Whole sections that could make entire films. Like this guy from D.C. – I asked him, "What if you had a daughter and she was a ho?" He said, "As a matter of fact my daughter is a ho, and my best friend is pimping on her."

Albert: We originally had a "trick" section. Two pimps told separate but identical stories about Alfred E. Bloomingdale. The girls would go over there, and he’d dress up in panties, and they would shit on him.

Filmmaker: You refer to the pimps as "sociopathic psychologists." What do you mean by that?

Allen: What I mean by that is the psychology they work on the girls. I wanted to get at the mystique of why and how they exert this mind control over the women. The girls have problems, the pimps have problems. And they specialize in pushing these buttons.

Albert: There’s one thing I learned about these pimps that I don’t think is entirely clear in the documentary. Even though they are manipulators and they prey on girls’ minds, I’ve noticed that regular relationship-type issues between men and women get carried out to the most extreme degree in the pimp relationship. They would never admit it on film but it’s damn near husband and wife.

Filmmaker: The fireworks sequences that bookend the film, along with the title, seem to be an overt critique of American capitalism. Did that analysis inform the structure of the film?

Albert: We thought it would be interesting to put "American" and "Pimp" in the same title, because nobody would think to put those together. They think of pimping as a Black, seedy thing. But it is as American as apple pie. It’s also American in the sense that [pimping is] capitalism at its best. One of the guys in the film says, "It’s like Lee Iaccoca – you got to make $15 million a year even if you’re paying employees $5 an hour."

Allen: Some pimps are a lot nicer to their people than I’ve seen Hollywood executives treat their assistants. We didn’t grow up in this town or in this business. We came here out of Pomona and saw how [Hollywood executives] treat people. We weren’t used to seeing people getting treated like that! In this town, it’s like a pimp-ho relationship. You’re either pimping or ho’ing.

Filmmaker: How did you find your subjects?

Allen: We knew one guy who was an indoor pimp who knew Rosebud. And Rosebud knew this guy, and they knew some others. L.A. might be hot, or Miami might be hot – they all go to whatever city might be hot. So if you know this guy, he knows that guy, and that’s how you get plugged into the culture. There are certain characters we got, but we didn’t get all the characters we wanted. We didn’t get the very top or the very bottom. We just got what we could get. The upper echelon of pimps – a couple are in here, but a couple are just so major that they wouldn’t even touch the film. They’re doing so much money and so much business, they’re living in Hawaii and they’ve got ten girls and are pulling in $1,700 a night average for one girl, tax free money. The lowest echelon guys are the ones that pimp the crack addicts, but they aren’t in the movie.

Albert: In the real pimp game you can’t have the girls on dope. And the pimp can’t be taking dope either.

Allen: That’s one I can give these pimps – there’s not too many that smoke weed or get into anything worse than that. I think 90% that we met didn’t do weed. They may be drinking beer once in a while, but most of them didn’t even drink. Strangely straightlaced guys.

Filmmaker: Do you think any of them will face repercussions for appearing in the film?

Albert: I don’t know – it really may mess up their lives. I’m not sure they thought through how this is going to be on the big screen.

Allen: They did, though, because they want to be known. They did it because they want to be stars. Because to them that may mean more ho’s.

Filmmaker: Legally, could the film be used as evidence in court?

Albert: The [police] can’t use the film to arrest someone. But, once [someone] is arrested, they can subpoena the film as corroborating evidence if they already have a case. If a girl turns on one of these pimps, they can subpoena all of our footage. But they can’t use the film to start a case. They thought they had a case with one of the guys in the film. When we interviewed the guy in jail, we told them to put us in a room with a lot of light. So they put us in a room with all these mirrors and I wondered if somebody was back there watching us. So we got done with the interview, walked off and then the FBI comes in and they showed a badge and everything. They were nice to us and everything but we wondered if they had been in there watching. We come to find out a month later from a reporter that they had been behind the mirrors, that the room had been full of cops watching us during the interview. So they seized the tapes and everything. Overall, though, they have not messed with us. That’s one thing I was scared about, because I just do not have good feelings about the FBI.

Filmmaker: Was the incentive to be on film enough, or did you pay these guys?

Allen: Some of them wanted to be paid, some of them wanted to bail one of their girls out. Some of them were like, "You don’t pay me because this bitch pays me. I’m not taking anything from you." It depended on the person.

Albert: The most difficult part of this was getting the right situations to put on film. Pimps Up Hos Down was an HBO project that was stolen from us. The guy who made it was our location scout for our last movie. We pitched [this movie] to Sheila Nevins at HBO on the phone while I was mixing Dead Presidents. And she said, "What are people going to think about the Hughes brothers doing a documentary on pimps?" She wrote me off. Come to find out they got together to do a cheap version of it. When you watch this so-called documentary, you see how hard it is to capture the essence of the pimps on film. This guy hired strippers to play prostitutes and used this footage... It just shows that you can’t just steal an idea from someone, make it really quick, and get it out before them because the quality shows up automatically. We spent two and a half years making ours. This guy shammed his together in six months with HBO.

Filmmaker: Did you think it would take you two-plus years to make this?

Allen: Initially it was a record label [Interscope] that gave us backing after we had originally financed some of it. They said, "Here, we’ll give you the money because we want to do the soundtrack. And at first we thought we could get it done in six to ten months. The average "Dateline" piece is done in a week. What we didn’t count on, as we were saying before, is that it’s so hard to get that natural situation. You can get the interview, but you can’t get all the other stuff. Or you find it’s not what you wanted so you might have to get another guy, fly here, fly there. A lot of things came up, and we realized that this is not a "Dateline" episode.

Albert: I knew it would take at least a year to do it, but I had no idea it would take two and a half years. We went to a second editor [Doug Pray] who really understood the project, who really organized things for us. About four months ago it started to form on its own. Every movie does that – it just makes itself all of a sudden. It takes on a life of its own. We had been sitting around waiting for this to happen. It could have taken another year.

Filmmaker: And you would have taken a year?

Allen: We would have taken it.

Filmmaker: Interscope was fine with that?

Allen: No, by that point we had severed with them. We own the film.

Filmmaker: How much did you put in and how much did they put in?

Allen: We put $150,000 in, and they put $600,000 in.

Albert: Originally the budget was $1 million. At one point we took a month off to look at the footage and reassess what we were doing.

Allen: It just became clear that this wasn’t like a music video so, basically, they gave up the rights. This is the best move we’ve ever made.

Filmmaker: Do you want to keep making documentaries?

Allen: We’ve gotten a little sick of the way the industry works and how long it takes to get a movie together and how the stars act about their paychecks. The bigger the budget, the less it’s about the film. So we started saying to ourselves that we should plan a documentary in between each film. We could get it off the ground really quick. We won’t have any studio interference. We won’t have any actors interfering. We learned a lot about ourselves doing this. The last time we did something like this we were 17. It was like the way we used to do it – get a camera and go out and do it ourselves. We’d forgotten that you could do it like this. You can really go make it yourself.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →