HUMANE SOCIETY

With Amores Perros, his visceral debut feature, Alejandro González Iñárrito immerses us in a frenetic and fractured portrait of contemporary Mexico City. Travis Crawford talks with the director.

Alejandro González Iñárritu photographed by Richard Kern

Amores Perros (inelegantly translated as Love’s a Bitch) brutally thrusts the viewer into its complex narrative with such lacerating visceral impact – dogs, careening cars, blood, smoke, screaming, handheld camerawork and jagged cutting – that it seems odd to refer to this opening as comforting, but, in a way, it’s true. Within only minutes, one is able to breathe a sigh of relief, sensing that Amores Perros will be the electrifying work of a dauntless filmmaker, and the remainder of its 154 minutes fully confirms this initial impression. That Amores Perros is a first film makes this confidence even more impressive.

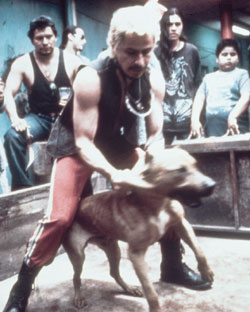

The directing debut of 38-year-old Mexican filmmaker Alejandro González Iñárritu, the film interweaves three separate stories through the metaphorical motif of dogs owned by the protagonists of each tale and with the narrative collision (literally) of a car accident that involves all of the film’s characters. The first and arguably most gripping story involves young Octavio’s love for his brother’s wife and his discovery of the family canine’s skill at dogfighting. (The ferocity of these sequences has led some to mistakenly believe that the dogfights are authentic). The film subsequently shifts to Valeria, a model disfigured in the car accident, and her increasingly strained relationship with Daniel, who has just left his wife. The final story is that of El Chivo, an embittered, vagrant hitman estranged from his family who seeks redemption and change.

Iñárritu’s interwoven triptych structure has led some critics – including those who should know better – to make the inevitable Tarantino comparisons, but the film’s humanism, richness of characterization and insight into Latino culture suggest more of a hybrid of Altman and Buñuel. For a film with such a necessarily nonlinear construction, however, it remains – like Pulp Fiction and Go in previous years – the most narratively engrossing film of the year.

Iñárritu began his career as a DJ and music producer in Mexico, vocations that bear an influence on Amores Perros both directly and conceptually. The film is driven by a forceful soundtrack, with Mexican rap and hip-hop seamlessly blending with acoustic ballads and Celia Cruz classics, interlaced through Gustavo Santaolalla’s droning, melancholic score. And Inarritu’s stylistic approach mirrors this musical eclecticism, as the film’s full-throttle introductory account of Mexico City’s impoverished ultimately transforms into a more sober, contemplative treatment when the film looks at the city’s privileged classes. These tonal shifts have undoubtedly contributed to the criticism that Iñárritu’s creative potency declines sharply after the superlative opening story, but this argument tends to ignore the tender, subtle triumphs of the latter two episodes.

Iñárritu’s narrative technique is not without its problems – for example, his decision to incorporate significant elements of the more sedate second and third stories into the first tale occasionally diminishes that section’s high-octane momentum – but it’s difficult to recall a recent film of such substantial length that utilizes its running time as expertly. Amores Perros had already won two awards – the Grand Prize at the International Critics’ Week in Cannes and the Best Director prize at the Edinburgh International Film Festival – by the time of its North American premiere at the 2000 Toronto festival, where Filmmaker spoke with director Alejandro González Iñárritu.

| |

| Photo by Rodrigo Prieto | |

ALEJANDRO GONZÁLEZ IÑÁRRITU: We became very close friends a few years ago – it was like finding a lost brother I didn’t know was in the world. I had read a script that he wrote that was never shot, and I fell in love with the dialogue and the humanity of the characters. Then we wrote a short film that was also never shot, but that became the seed of what happened later. Mexico City has so much going on that it was difficult to capture it all with just one story. So we decided to play with three stories. We had too many things to say, so this structure helped us. The writing process took three years.

FILMMAKER: Were the three stories always designed to interconnect with linking characters, or was there ever a point when they stood as three separate, unrelated tales?

IÑÁRRITU: Well, the idea was to make a movie about love, death and redemption, focusing on the painful process of learning to love somebody. So deciding when and how the characters’ paths would cross was a tough decision, because that’s what makes the difference between three short films and a whole movie divided into three stories. From the beginning, we decided that the accident would be the main thing, that it would explode in the center of this universe, and the pieces would balance out, even when we would go backward and forward in the structure. The car accident exposes the fragility of life – you make plans, then you go out and a car crash changes everything.

FILMMAKER: At what point did you introduce the canine metaphor? Was that always a part of the story, or did you come up with that later as a linking device?

IÑÁRRITU: No, that was always a part of it from the beginning. The first title of the movie – which I didn’t like – was Black Dog, White Dog, but then [Emir] Kusturica’s film [Black Cat, White Cat] appeared. But from the beginning the movie was a metaphor: black dogs, white dogs, rich people, poor people. That element was always there.

FILMMAKER: Was it hard to get this first movie off the ground in Mexico?

IÑÁRRITU: I was very lucky – the producers, from a new company named Altavista, were very brave, and they loved the script. They actually jumped at it and joined together with my company, Zeta Film, and they have a lot of guts to have done that. But you know, the most difficult thing is not the money. It’s just getting a good story. Once you have the story, there’s money waiting somewhere.

| |

| Goya Toleda in Amores Perros | |

FILMMAKER: To what degree do you see Amores Perros as being a uniquely Mexican story – a portrait of Mexico City and the dogfighting world – as opposed to a more universal story?

IÑÁRRITU: I think it’s a very universal story because it’s a very local story. That’s what makes Amores Perros a story that can touch anybody. I’ve shown the film at Cannes and here in Toronto, and it’s strange how different cultures and sensibilities can connect emotionally to the material. But I never really show Mexico City in the film; you can never recognize it in the movie. To me it’s only the battleground for the emotions in the story. I never wanted a scenario that would say, "Look at what’s happening in this city!" But people who’ve been there tell me they could smell Mexico City in the film, they could breathe the same air. The film is an exploration of how and why Mexican society has lost our fraternity and [also] an exploration of parents: the father doesn’t exist in the first story, the father leaves in the second story, and the father returns in the third story. We’re a society that had been ruled by a 71-year-old party, and the change was a painful process. This picture appeared in Mexico two months ago and was a big box-office success. Why? I think that if this movie appeared only one year ago, people would not have been ready to see ourselves and have the courage to change. But now people have hope and a new attitude. It’s a social and political change in Mexico, and it’s painful, but it’s the only way to confront yourself.

FILMMAKER: There have been rumors that the dogfights in the film are real and resulted in injury to the animals, but the closing credits contain a disclaimer stating that the animals’ welfare was monitored. How did you go about achieving those sequences?

IÑÁRRITU: First of all, I have a dog and I love dogs. It was very complex and difficult to reproduce a real dogfight, to achieve a level of realism without hurting the dogs. I hired an American guy who supplies animals for all the feature films in Mexico, and all of the actors were trained to handle the dogs; it was a lot of work. During shooting I tried to construct emotional stress within the dogfight scenes but put very little explicit footage of the actual dogfights.

FILMMAKER: That’s true – we only see the dogs connect very briefly, and then you cut to the faces of the actors.

IÑÁRRITU: Exactly, because it’s not about that; it’s only one element of the first story. I didn’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings, but I felt I had to show the blood because I wanted to unnerve people, since that’s how I felt when I went there to actual dogfights, in order to reproduce them. I thought, "They’re going to kill me." But the way I did it was, we took invisible fishing line, painted it the color of the dog’s hair and attached it to them. These dogs are also trained for personal security, so they’re trained like this, and to them, they’re playing. Sometimes they would start making love in the middle of the scene; it was very funny. With the handheld camera and the sound design, it seems real, but if you pause the DVD, you can see the technique. When they were supposed to be dead, we would inject them with a veterinary anesthesia for 20 minutes — their owner was always there, shouting, "No more than 20 minutes!" I treated the actors worse than the animals!

FILMMAKER: The visual design of the film is also very distinctive, very high-contrast, shot through with vibrant colors. Tell me how you collaborated with cinematographer Rodrigo Prieto to realize this look.

IÑÁRRITU: I thought the material demanded a very specific aesthetic. The architecture and colors of Mexico City can be so kitsch, but it has a beauty all its own. It has a lot of character, and I wanted to achieve that very vibrant feeling. I love the work of Nan Goldin, so the first meeting I had with Rodrigo, we looked at a book of her work, and I told him, "This is the look I think I need." So we began to make experiments in the lab, and our conclusion was to use this Vision 800 color stock, with a silver-retention process in the negative. It was the second time in the world that anyone used this. In the United States they say they don’t want you to do that because it’s very risky. But it gave us those electric earthtones, and it was terrific. I think it really helped the movie — it has something you cannot explain, but it makes it different. Maybe we lost our negative, but we’ll have it on DVD.

FILMMAKER: Amores Perros is the type of film that displays a real passion for, and knowledge of, cinema. Who were some of your influences when you made the film? I know some critics have postulated Tarantino, which I don’t really see.

IÑÁRRITU: [Laughs.] The Tarantino thing is funny — I think people have credited Tarantino with the invention of the three-story structure, but what about Faulkner and García Márquez? And there have been so many films that have used it too, but suddenly Tarantino gets the credit for that. I don’t have anything to do with Tarantino, except for maybe the approach to violence more than the structure. I live in a violent city, and when you live in a violent city, you’re not going to make a fairy tale or a comedy about that. Violence has very painful consequences, and that’s my statement. But I have a lot of directors that I admire. The classics, like Bergman, Fellini, Buñuel, Tarkovsky, Leone, Scorsese, Cassavetes — I love Cassavetes. I’m a pretty eclectic guy in that sense. But lately, the people that really shake me are Lars von Trier, Wong Kar-wai and Ang Lee — they are approaching films in new ways.

FILMMAKER: Perhaps it’s only appropriate for a film called Amores Perros (Love’s a Bitch), but your movie has a somewhat bitter take on love and human relationships, and most of the film’s main characters wind up pretty unfulfilled at the film’s close. Does this reflect your own personal view of relationships, and can you foresee happiness coming to any of the film’s characters after the events in the film?

IÑÁRRITU: I think life is an ongoing process of loss — you’re losing things all of the time. These characters lose many things by the end of the film: innocence, lust, love, hope. Yet at the same time, learning to love somebody, and learning to love yourself, is a very painful process. Love is a very dominant emotion, and it can be very destructive at the same time — it depends on the way you’re using it. Man has a divine nature and an animal nature, and when the animal nature controls you, your decisions are going to have a lot of consequences. For me, this movie is about how these characters that I love — weak characters, not strong characters, people that can really be broken — go through that painful process of learning in which [one gets] a little better. To my point of view, that’s life. At the end, even with all the circumstances, there is hope because you can change your life, you’re the owner of your destiny. And we can redeem ourselves with love — that’s the only way we can be more than flesh and bone.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →