OUR MAN IN CAMBODIA

In City of Ghosts, Matt Dillon makes his directorial debut with a complex noir set in post—Khmer Rouge Cambodia. Scott Macaulay talks with Dillon.

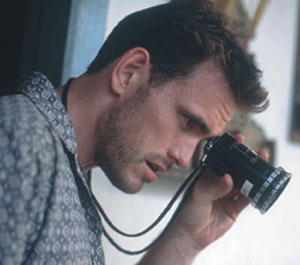

Actor-director Matt Dillion on the set

of City of Ghosts. PHOTO: ROLAND NEVEU

In Matt Dillon’s big-screen directorial debut, City of Ghosts, Dillon plays Jimmy Cremming, a New York insurance company executive who takes off after a crooked business partner, Marvin, played by James Caan, who has fled to Cambodia with the company’s assets. In Phnom Penh Cremming encounters both Marvin, a sort of fallen father figure, as well as a raft of colorful European expats and Cambodians all navigating the country’s post—Khmer Rouge politics.

As compelling as all of these characters in City of Ghosts, including Gérard Depardieu as an overbearing café owner and Natascha McElhone as a beautiful art restorer, is Cambodia itself. Vibrant, glowing with a strange, vaguely menacing beauty, Cambodia and its "country in transition" vibe ground Dillon’s noir storyline while giving it a dramatic unpredictability. Having repeatedly visited Cambodia for over 10 years, Dillon, in the first film shot there since Lord Jim in 1965, guides Jim Denault’s roving camera across the landscapes and into the faces of the people, navigating a country just now recovering from the trauma inflicted by the Khmer Rouge. Eschewing easy morality and the Anglo-centrism usually found in these "American abroad" stories, Dillon has made as his first feature an intriguing neo-noir that can be lived in as much as watched and experienced.

FILMMAKER: What made you set your first feature as a director in a foreign country, Cambodia?

Matt Dillon: Well, there’s an old thing that Hemingway said: "Write about what you know," right? And [then there’s the opposite]: "How dare you write about something you don’t know anything about?" I feel that you can write about what you know, but you can also use [writing] as an opportunity to discover something new that you didn’t know. You just trust your heart and your gut and go with it, and that’s what I was doing. What do I know about Cambodia? Well, it’s a place that has fascinated me for a long time and it just seemed right for a film setting.

FILMMAKER: When did you first travel there?

DILLION: When I first went, in 1993 I think, the U.N. was there. I wasn’t planning on going – I was just traveling on an extended vacation to Thailand and Vietnam with some friends. I’d been burned-out doing three movies back-to-back and needed a break. A friend who had been living in Bangkok for 30 years recommended that I go to Cambodia because nobody was really sure what was going to happen there. [At the time], people were quite pessimistic, thinking that the Khmer Rouge were going to make a last stand. And then in 1993 the country held its first elections in how many years, which, by U.N. standards, was a real success. But there was still this foreboding sense – a sense of danger as well as tragedy. And then I read an article stating that a number of the world’s most wanted criminals were thought to be hiding in Cambodia to take advantage of its lack of extradition treaties. I thought that was interesting because [I met people there who] were clearly running from something. So, this idea of taking an American out of the U.S. and into this world became interesting to me.

FILMMAKER: It took years to develop the script and then get the movie made. How did the changing politics of the region affect your process?

DILLION: Like a lot of the Third World, especially Asia, Cambodia is such a rapidly changing place, and I always had to be readjusting the script. When I started writing the script, the Khmer Rouge existed as a political force to be reckoned with in Cambodia. By the time we began shooting, the Khmer Rouge basically had been disbanded, which is not to say that their thugs are not still roaming the countryside. Most of the kidnappings and abductions in my film are based on real things.

FILMMAKER: How did the collaboration with your co-writer, Barry Gifford, come about?

|

| Matt Dillion and Gérard Depardieu in City of Ghosts. PHOTO: ROLAND NEVEU |

FILMMAKER: Were there any models for this type of story that you looked at?

DILLION: Films?

FILMMAKER: Yeah, or even books.

DILLION: Obviously Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness for the story of going into darkness and coming out of the other side. Carol Reed’s films, particularly Outcast of the Islands, which is one of my favorite movies. We also looked at Brother Orchid starring Edward G. Robinson – this gangster comedy set in the ’30s. Sam Fuller’s House of Bamboo – I love his storytelling. The sad thing with [Fuller’s movies] is that he was either such a purist or they had so little money that he wouldn’t get the coverage that he needed. House of Bamboo is brilliant, and then the ending, the last heist they pull – there’s no coverage! Also, with Jim [Denault], Barry and I watched [Carol Reed’s] Odd Man Out several times.

FILMMAKER: Watching the film, it seemed pretty clear that you had scenes lit for 360 degree coverage so you could always be grabbing things. You seemed to have tons of coverage for a shoot that happened quickly.

DILLION: We really needed two more weeks to finish shooting, so, I liked the mobility of handheld to change shots [quickly]. I don’t like handheld [camerawork] as a style, when people formalize it like, "Let me show you how handheld we are," but I like the freedom it gives you. Having to be in both places at the same time, handheld really gave me a lot more latitude.

FILMMAKER: What were your biggest challenges with editing the film? What sort of priorities came forth? Was it more about storytelling? Or was it more about keeping other elements in the film?

DILLION: I had a very good editor in Howard Smith, and I was told by wiser people with more experience than me: "Look, there will be a scene that, while you are making the movie, you’ll think is untouchable. And then [in post] you’ll cut it and not look back." That’s what happened to me on more than one occasion. Just looking at the movie over and over again gives you all the answers that you need. Each time I would watch it, the movie would sort of dictate its pace, its length, what needs to happen. You know, I wasn’t interested in making the most perfect movie. I was as much interested in the atmosphere, the texture, as I was in the story. Without the story, of course, you really don’t have a movie, so you have to have a good story. But I don’t believe that anything that isn’t driving the story should be thrown out. I mean, I like dream sequences; there’s a lot of people who will tell you there’s no place for dream sequences in storytelling, but I don’t think you can exclude the subconscious. Interestingly a lot of the directors that I’ve worked with and have been influenced by have used dream sequences – people like Gus [Van Sant], Francis [Ford Coppola], Tim Hunter.

FILMMAKER: What did you take from your experience as an actor to the film, how you made this film and the decision to make it?

DILLION: One thing is to trust actors. In my experience, the films that I’ve had the most success with were with directors who were open to leaving it open to discussion. So I tried to do that too. Good actors, I have found, have a good sense of what is true. I might write bullshit dialogue, some dialogue that’s not good, but sometimes you just have to just put something [down on the page]. It might not be the way a character would say it, and [you have to give the actor] a little time to find it.

FILMMAKER: The film blends professional actors very nicely with what seems like real people. How did you approach the casting process?

DILLION: I had great luck with casting. I would see people walking around the street and I’d say, "Let’s put them in the movie." You can do things like that in places like Cambodia or Mexico. It seems like it’s very difficult to do that in the States anymore. I also stylized characters based on [real people] I had seen [in Cambodia]. I had a guy working with me on the film, an advisor-consultant, and on New Year’s Eve he took me to Battambang, the red-light district that was sort of the last frontier deep in Khmer Rouge territory. There were these two brothels on the sides of this dirt route, and there was real tension in the air – guys in black shirts lurking around the doors. So, we went inside one, sat down, and they paraded out a bunch of strange-looking girls, and this guy came out who was like the devil himself – long fingernails, greasy, wavy hair, flip-flop sandals and a jacket. He was the scariest fucking guy I’d ever seen. We didn’t stick around. I said, "That was fun, and we’ve got some visuals to take back with us." And when we got out, the driver told us there had been a shooting right before we arrived and they were all waiting for the retaliation. In any case, I’d remember all these details, and when it came time to cast [one of the characters], I designed him [based] on the guy in Battambang.

FILMMAKER: What are you working on next?

DILLION: Well I’m working on this screenplay with Mike Jones about this guy Eddie Maloney, who was this kind of modern-day Rasputin. He was shot something like eight times [in his life]. After he was shot the second time, the Daily News headline was "He Eats Lead!" So we’re doing a script based on this guy’s crazy life.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →