FANTASY ISLAND

Henry Darger was in many ways the quintessential outsider artist: uneducated and unknown during his lifetime, then celebrated and scrutinized for years afterwards. Oscar winner Jessica Yu’s new film, In the Realms of the Unreal, should widen his already sizable audience. Peter Bowen reports.

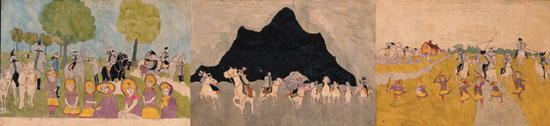

Watercolors from Henry Darger’s epic illustrated novel, In the Realms of the Unreal. HENRY DARGER ARTWORK © KIYOKO LERNER. |

One film this winter details a wild fantasy world where good and evil are locked in an endless war, where small, childlike people fight fierce military giants, where strange beasts and dragons coexist in lush, exotic landscapes. No, not Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King, but Jessica Yu’s In the Realms of the Unreal, a documentary about the outsider artist Henry Darger. (The film premieres as part of the Documentary Competition of the 2004 Sundance Film Festival.)

|

The Los Angeles–based Yu, who won an Academy Award in 1996 for her short documentary Breathing Lessons: The Life and Work of Mark O’Brien, first encountered Darger’s pictures nearly 20 years ago but found them generally unsettling. “The subject matter — little girls with penises running around shooting people — immediately seemed very perverse,” she recalls. It was not until 15 years later, in 1999, that the idea for a film came to her. “I was in Chicago giving a lecture related to my previous film, The Living Museum,” Yu recalls, “and somebody in the audience asked if I had heard about Henry Darger. This guy took me to meet Kiyoko Lerner [Darger’s landlord and subsequent guardian], and she showed me his room. I wasn’t thinking that I wanted to make a film, but being in that room inspired me. It was such a beautiful space.”

Yu spent the next year researching the project — sorting through records, trying to piece together Darger’s life, reading his manuscripts and studying his art. It quickly became apparent that the project posed challenges in two opposite extremes. About Darger the man, there was only a scant record: three photographs, a small group of people who knew him only in passing, and a faint history culled from county and institutional records. His volume of work, however, was overwhelming and impossible to fully comprehend. Her strategy became to meld these two problems in an aesthetic approach.

|

“When he first started he couldn’t really draw,” Yu explains, “so he would cut things out of advertising, magazines, newspapers, even his favorite books, and then paste them in or trace over them. So I started to look for things that related to the time — postcards, ephemera and such — to incorporate in the film.” More importantly, Yu felt that Darger’s animated style gave her license to re-create the way his images might have appeared in his imagination. “Animation was something that I decided on early on,” she recounts. “It was a huge liberty to take, but at the same time, I looked to the work’s own experimentation. I told the animators to use only what was in the painting and to only depict the action suggested by the work. Also, I wanted to have the animation become more complicated as the film went on.”

Like Yu, most scholars of Darger have attempted to connect the man with his work. Previous studies have highlighted his tragic and impoverished background (his mother’s early death, the abuse he suffered at the Lincoln, Ill., Asylum for Feeble-Minded Children). Others have tied him to spiritual poets such as William Blake, or proto-perverse ones such as Lewis Carroll. Some see his early appropriation and use of popular and commercial imagery as foreshadowing the work of Andy Warhol. Still others have conducted historical detective work, speculating on his being a pedophile or worse, a serial killer. But Yu’s film mostly provides a glimpse into Darger’s imagination and the satisfaction he himself realized from it. “In the Realms of the Unreal was not written for the experience of sitting down and reading it again,” Yu says. “It was written for the pleasure of writing it. He would come home from a lousy day of scrubbing floors and enter this world of adventure. For him, each night presented the chance: ‘Okay, what happened today? Let’s have a bigger battle than yesterday.’ ” Darger, she concludes, spent his life trying to defy John Donne’s claim that “No man is an island, entire of itself.”

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →