ART AFTER DEATH

Don Argott’s latest documentary, The Art of the Steal, depicts the fight to control Philadelphia’s Barnes Collection, a private collector’s museum of Impressionist and early Modern art, as the heist of the century.

By Scott Macaulay

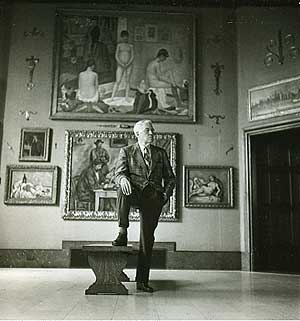

ALBERT C. BARNES WITH HIS COLLECTION OF ART.

From its title to its “just the facts, ma’am” pacing to its spirited underscoring, Don Argott’s The Art of the Steal places itself in a long cinematic tradition of art-heist stories. Like a present-day The Thomas Crown Affair, Argott’s film tells the tale of a group of cool customers who abduct a stash of Impressionist masterpieces out from under the eyes of their owner, a cranky industrialist collector. Of course, though, The Art of the Steal, which has received rave reviews at the Toronto and New York Film Festivals, is a documentary, not a dramatic thriller. The paintings’ owner is not some billionaire with a high-tech alarm system but instead a deceased Philadelphia businessman who watches from beyond the grave as the instructions in his will — to maintain the collection in his elegant private museum to which serious art lovers are admitted for free in small group, day-long viewings — are challenged by philanthropic bigwigs who would like to see the paintings moved to new tourist-district galleries. And the theft occurs not in the dead of night but in a courtroom, as foundation officers and city officials, claiming that the financial distress and mismanagement of Barnes’s foundation demand a new home for the paintings, battle a group of local activists, the Friends of the Barnes, who argue that more can be done to make the collector’s original vision viable. By reaching for this art-heist metaphor, Philadelphia-based Argott, whose previous films are Rock School and Two Days in April, has made an entertaining and suspenseful film that is actually more about the political intricacies of the non-profit museum world than it is about an actual crime.

I will confess to flashing on Casablanca’s Captain Renault, who memorably said he was “shocked” that there was gambling going on at Rick’s casino, while watching this film. The idea that city officials employ hard-knuckle tactics when leveraging art for tourism and economic development, that non-profit boards can be influenced by business and social connections, and that ideological contradictions exist between collecting and connoisseurship seemed to me, someone who began his career in the non-profit art world, less shocking allegations than the film may have intended them to be. But The Art of the Steal worked for me anyway, though, because, as Argot notes below, its true subject is much larger than a local museum controversy: He is ultimately describing the fate of art appreciation in our Googled, watch-it-now culture. In a time in which the directive to independent filmmakers is to make their films available whenever and wherever the audience wants to view them, Argott is sticking up for the enriching pleasures of scarcity, dedication and viewing environments that are as finessed as the artworks themselves.

The Art of the Steal premieres this spring as one of the first titles from Sundance Selects, which will release it theatrically in 15 cities as well as, um, on Video On Demand.

DON ARGOTT. DIRECTOR OF THE ART OF THE STEAL.

So how did you go from documentaries about rock music and the NFL Draft to one that details the intricacies of the museum world? This film came to us from Lenny Feinberg, the executive producer. He’s a gentleman who lives in the Philadelphia suburbs. Being from this area you don’t have to go very far to get peoples’ take on the Barnes. The story stuck with him, and he was itching to tell it. He found us through [Genevieve Jolliffe’s] The Documentary Filmmakers’ Handbook, which [producer] Sheena [Joyce] and I were interviewed for. He just called us up. I knew a little about the [Barnes Foundation] and the more we delved into it, the more I thought it was an incredible story. We would be the first to tell this story from the ground up. There is a ton of misinformation out there.

Is Feinberg from the art world? He is in real estate, and he really wanted to make this leap into filmmaking.

So what happened after he contacted you? Everybody says they have a great idea for a film, but you want to make sure there is enough [in a subject matter] to do a documentary. So the first thing we did was a teaser to test the waters and see if there was enough of a story. We did a bunch of research and found some key people to interview to see how candid people would be. We put together eight or 10 minutes and afterward [we] all felt there was a lot more to the story.

How did the relationship evolve between you and Feinberg? Did he have his own editorial agenda he wanted you to follow? Our company, 9.14 Pictures — myself, Sheena and Demian Fenton — did Rock School and Two Days in April, so Lenny trusted us artistically. We were the experts in terms of making the film. But he had very strong opinions on the topic, and part of the process was [myself, Sheena and Lenny being] brutal with each other. We were constantly pushing each other. You want to push each other, and having Lenny in there as another viewpoint pushed us to make it better.

But did he have a particular agenda he wanted the film to represent? He might have, but he never imposed it on us. We didn’t come at this with any preconceptions or agenda. I think Lenny just felt it was a great story.

So he wasn’t part of Friends of the Barnes? No. Zero affiliation.

What are your own tastes in visual art? I’m a huge Dali fan — that’s the kind of art I respond to. This particular period, early Modern and post-Impressionist, I respect it, but it’s not my favorite kind of art. But one of the things that sealed the deal for me was going to the Barnes. You walk into the place, and it’s breathtaking. It’s really overwhelming — something special and beautiful. I’ve walked into that main gallery many times, and I still get chills. Going there the first time, I thought, “How the hell haven’t I heard about this? Why isn’t there a ton of people here all the time? Why isn’t this more widely known?”

What were your biggest challenges in making the film? I think the biggest challenge was access, specifically to the Barnes. We overcame most of the challenges, but the one thing I wish that we had was [permission to] shoot inside the Barnes. Unfortunately they didn’t want to cooperate with us. They didn’t want to be interviewed and didn’t want to give us access. And as we got going, unfortunately, the people we are the most critical of [in the film] didn’t want to talk to us either. We approached them at least a dozen times. Ray Perelman, Rebecca W. Rimel, Bernie Watson — we knew after the first [approach] they weren’t going to talk to us. But you have to do your due diligence and try.

Why do you think they refused to talk? You’d have to ask them. I’m sure everybody’s got his or her reasons. When you peel back the layers and see how corrupt certain aspects of the story are, it’s not surprising. But we set out to honestly tell the story in the best possible way. There isn’t a narrator, which I like — we are not the voice of God. We were trying to mine for the most-compelling sound bites of the [different] point of views.

Did you always intend for the film’s style to be that of a gripping procedural? The film evolved into that when we began to structure it, and [that style] turned out to be the most appropriate way to tell the story. Our goal was to make it bigger than a local story. We wanted to explore larger themes of culture, the value of art and ownership. You know, [Sheena and I] have been to Ireland several times, and when you go there you feel like you step back in time. There’s beautiful reverence for history there that we don’t have in the U.S. We are a young country, and we don’t respect our history as much as we should — especially in Philadelphia, where it should all be about preserving the history. We have Independence Hall and the “Rocky Steps,” and [you would think the Barnes Collection] would be something we’d want to champion and preserve as well. But it’s the opposite of that, and that’s a travesty. As much as the powerful people involved, The Pew [Charitable Trust] and the Annenberg [Foundation] do great things for Philadelphia, it doesn’t mean they don’t make mistakes and shouldn’t be held accountable for them.

The voices in your film are passionate about preserving Barnes’s vision, and their opposition is mainly portrayed as coming from those with commercial, power-related or egoistic motives. But there is an argument that moving the collection is in the best interests of the art itself. Let me quote from the art critic Roberta Smith, who wrote a piece about the court decision in the New York Times titled, “Does It Matter Where This Painting Hangs?” She wrote, “The decision is a triumph of accessibility over isolation, of art over the egos of collectors and, frankly, of the urban over the suburban. In other words, the gains may ultimately outweigh the losses. Of course, it is great to see paintings in an intimate setting that glows with the patina of time and bears the imprint of a collector’s personal vision. But it is also correct to ask whether a collector’s wishes, especially when they are restrictive, must be observed in perpetuity. The Barnes collection is not the Sistine Chapel ceiling. Barnes didn’t make the art; he bought it, one movable object at a time. Very few things remain the same forever, and they change largely because of human need.” What would be your response to this argument? Our goal in making the film wasn’t to pass judgment. We tried to tell a character-driven story with Albert Barnes as the main character, and diminished [in this whole debate] is Albert Barnes, the human. He has become just a concrete slab with a name on it. It is easy to say, “Well, he is dead and gone [so why adhere to his wishes]?” It is a compelling argument that gets into interesting areas. “What if he said this, what if he said that?” Well, the reality is, he didn’t say those things. He just said, “Preserve it the way I want it to be.” Should you be able to argue with that? You can say, “The guy was a jerk, therefore we should do whatever we want,” and, frankly, that’s been the attitude, whether it was on purpose or just happened. He’s become this eccentric kook, a curmudgeon, who hated everybody. That doesn’t mean, though, that you should be able to decide the fate of his art against his wishes. If there’s one thing I hope the film [conveys] is that Barnes’s wishes are not being honored. The idea of adhering closely to a will is being violated. How much was done to help people see the art [at the Barnes Collection]? It’s a major leap from “he died, it’s not working” to “let’s just move the whole thing.” If a place is running a million-and-half-dollar deficit, wouldn’t it be easier to make that up than raising upwards of $300 million to build a new building that doesn’t need to get built? But there is a bigger idea behind this story — a comment on our culture. We get everything we want easily these days. We don’t have to work for anything. You can’t just walk in [to the Barnes]. It’s a pain in the ass [to make an appointment]. These days, people have a hard time with that. His demands weren’t ridiculous — he just wanted you to want to be there and to take it seriously. The Barnes is a shining aspect of a different era. Again, that’s all through his eyes.

You’ve initiated your own documentaries, and then you’ve also boarded projects like this one, which was brought to you. Is filmmaking your sole source of income, and what’s it like to run a production company focused on non-fiction? We own our production company, Demian Fenton is our staff editor, and this is all that I do. This is how we make our living — doing feature-length docs. That’s the model we set up when we did Rock School. We are not making much, but we are making a living. It’s very difficult, and now more than ever with the economic climate. We try to do one feature every year and a half, and then we also do corporate work for Sony Music and Nickelodeon — smaller scale projects with quicker turnarounds. But this small scale [work] has not been holding up since the beginning of [2009]. Unfortunately we anchored ourselves to the music industry — behind-the-scenes, EPKs, concert videos — and that wasn’t doing well to begin with. We have tried to get into reality TV, more like documentary series on the Sundance Channel and IFC. Non-fiction storytelling in the vein of stuff like [shows from] World of Wonder. But television is tough. It’s like lightning in a bottle. They only want to work with people they have worked with before. [Cable networks] are not interested in doing TV that comes at it from an outsider’s perspective. So we are relooking at our business model. Should we be focusing our energies on documentary features or should we get into the narrative world and do feature films? The problems there, though, are the same. You are only as good as your last film. We did a film after Rock School that Netflix commissioned, but it didn’t get out there for various reasons. We spent two years on it and it didn’t have the same impact. And then all of a sudden I’m not that relevant a filmmaker.

This film, then, is a real turnaround for you with the Toronto and New York Film Festival acceptances. It’s huge. We’re really humbled by it, and we’re hoping we can capitalize on it. The people who continue to work [as documentary filmmakers] are the ones whose work stays in the public eye.

VOD CALENDAR

See the VOD Calendar →

See the VOD Calendar →

HOW THEY DID IT

PRODUCTION FORMAT: HDCam.

CAMERA: Panasonic HVX200

TAPE STOCK: P2 HD

EDITING SYSTEM: Final Cut Pro HD.

COLOR CORRECTION: DaVinci 2K HD at Shooters Post and Transfer. Film out at Fotokem LA.

GO BACK & WATCH

THE RAPE OF EUROPA

Richard Berge,

Bonni Cohen, and Nicole Newnham’s

2006 documentary brings to light the

Nazi’s systematic looting of museums,

galleries and private collections across

Europe during their World War II.

REMBRANDT'S J'ACCUSE

In this 2009

film essay, Peter Greenaway treats art

history as a detective novel, traveling

to Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum museum

to decipher the murder mystery at the

heart of Rembrandt’s masterpiece “The

Night Watch.”

RUSSIAN ARK

Russian filmmaker Alex-

ander Sokurov’s 2002 single-take video

steadicam of the Hermitage Museum in

St. Petersburg conjures up a dream-like

trip into the life and soul of the revered.