Back to selection

Back to selection

“I See No Difference Between the Two”: On Cinema’s Role in Society

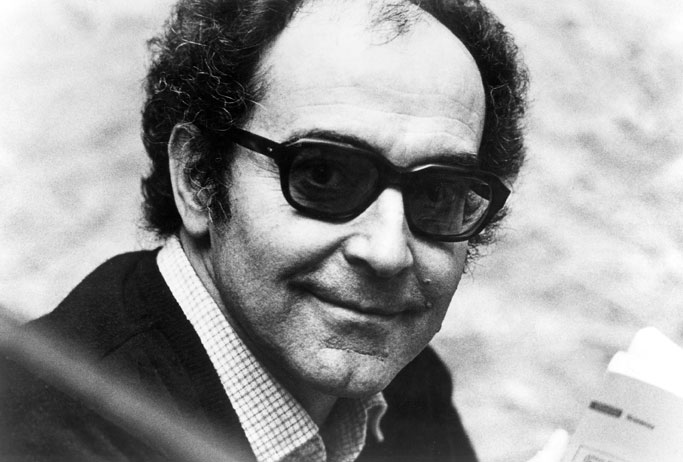

Jean-Luc Godard was a guest at the University of Southern California in 1968, discussing his work on a panel with King Vidor, Roger Corman, Peter Bogdanovich and Sam Fuller. This was at the close of a cinematic decade that Godard had owned; now, breaking with his previous work, he was becoming more political and less accessible. One of the discussion’s most telling moments came toward the end, when an audience member asked, “Monsieur Godard, are you more interested in making films or making social commentary?” Godard coolly replied, “I see no difference between the two.”

At that moment, the role filmmakers had traditionally played in society — that of mere entertainer — was dissolving. Godard was becoming involved with the student movement in France. Chris Marker, Alain Resnais, Godard and others began making “Cinétracts” — shorts shot on 16mm documenting political goings-on in a decidedly guerrilla fashion. A few years later, the “New Hollywood” of the ’70s would yoke cinema to the troubled post-hippie American youth, with reverberations that echoed throughout the culture: In April, 1971, Esquire’s cover story was Two-Lane Blacktop, and the film’s complete script was published inside. This period was the apex of filmmakers’ involvement in the cultural conversation. Understandably so — in the ’60s, cinema went from being entertainment to art as filmmakers gained an intellectual legitimacy and cultural currency they had previously been denied. Additionally filmmakers weren’t the only artists exceeding the boundaries of their work — novelist (and later filmmaker) Norman Mailer ran for mayor of New York City in ’68, and musicians’ roles in the politics of the time are well-known enough not to need description.

While artists are still regularly involved in what we term the “cultural conversation” — the exchange of ideas across a broad platform regarding the state of the country and its culture — filmmakers seem to have been left behind. Jon Stewart and Stephen Colbert, two perceptive comedic satirists, recently held a rally in Washington that drew 200,000 people. Nationally prominent novelists such as Joyce Carol Oates and Jonathan Safran Foer voice criticisms on op-ed pages and in public forums, revealing that for these writers, a world of importance exists beyond the literary. Plenty of musicians regularly perform in order to bring attention to cultural issues, political and otherwise.

Where are filmmakers in this mix? Almost nowhere to be found. Cinema was once the country’s most popular art form, yet can you imagine even a screenplay excerpt, let alone an entire script, being published as part of a cover story in Esquire today? As it has made its way from center stage, overtaken by Internet-based entertainment and less traditional forms of media, so too have filmmakers relinquished a position in the country’s consciousness. This diminishing of filmmakers as visible public personas is in part an effect of film losing its popularity as an art form, but it is also, cyclically, expediting that decline.

In America 2010, visibility and presence breeds interest. That much is for certain. When was the last time you saw a filmmaker in the news in relation to something other than their work or the field of cinema? Certainly some actors try to be politically active, but to people reading about those exploits actors are celebrities, not artists. There are plenty of filmmakers who delve into social issues within their work — Charles Ferguson’s Inside Job and Davis Guggenheim’s Waiting for “Superman” are two recent examples — but few seem to have the out sized Godardian/Mailer personality needed to become a public figure causing a stir for what they feel is important. The one notable exception is Michael Moore, whose cry of “Shame on you, Mr. Bush!” at the 2003 Academy Awards ignited the sort of political firestorm the industry would do well to originate more often; in the years since, Moore has been a regular guest on various talk shows, often discussing politics rather than his own work.

The rabble-rousing personalities of giants like Mailer and Godard weren’t simply useful in creating interest in the issues they raised, or those artists’ own works; they also fostered a sense that practitioners of film and literature were interested in something larger than subjects delimited by the mediums they worked in. The formation of a project like Cinétracts sent a clear message that cinema, as an art form, had a powerful link to the goings-on in larger society; what cinema had to say didn’t occur in a vacuum. By contrast, look at the stir (or lack thereof) caused by Ferguson’s and Guggenheim’s films. The cultural reaction to these penetrating looks at major societal problems has been minimal, which is shocking, especially considering that Inside Job is the first film to take a penetrating look at the financial

crisis of 2008. Indeed, for a film to get on the op-ed pages of the New York Times, it has to be nothing short of the highest-grossing film of all time: David Brooks devoted a column to Avatar, and that film seems to be the most recent work that incited any kind of zeitgeist.

So how do filmmakers go about regaining the kind of cultural authority they once possessed? How do we arrive at a world where the latest work from Ferguson or Guggenheim (or, for that matter, Paul Thomas Anderson or David Fincher) receives the kind of serious consideration recently bestowed upon, say, Jonathan Franzen’s Freedom, which dominated the media upon its release for its wide-reaching portrait of America during the Bush years?

To no small degree, the answer lies in filmmakers pursuing any and all extracurricular activity that suits their interests. While a grand proclamation would be satisfying, this kind of cultural engagement is too specific to different individuals for any general program to really apply. Mailer’s run for mayor was a brilliant move, but it would hardly have behooved the world of literature if John Updike or Philip Roth had a go at comptroller. Certainly, as video becomes ubiquitous on the Internet, one imagines that filmmakers armed with video cameras could make short, simple films at a fast clip, on a wide smattering of subjects as they see fit; those videos could be posted to personal websites or the sites of larger organizations, fitting into a larger effort of some sort. It could be thrilling to see politically-engaged filmmakers like Ryan Fleck and Anna Boden or Kelly Reichardt working on videos for, say, The Nation’s website.

That’s a general suggestion, a little predictable and one that recalls the aforementioned Cinétracts of 1968, but it would be a start. What really would drive this kind of cultural involvement would have to be defined by the specific passions of the individual filmmakers. For some filmmakers, the answer would be publishing in newspapers, journals, magazines or websites on any subject other than film. Sometimes all it takes is working in different formats: While he’s certainly not recognized enough to cause much of a stir, Chris Marker, in addition to compiling one of the finest bodies of work cinema has to offer, has made videos for museum installations, created and released his own CD-Rom (Immemory) and worked as an “undercover” photographer. His covert photos of persons of varying ethnicity on the Paris metro are as harrowing, given that country’s escalating xenophobia, as they are beautiful. Marker, who snapped the photos recently (at 89 years old!) published them, of all places, on The New Republic’s website.

It’s Chris Marker’s unyielding frontier spirit — that desire to push the limits of the medium, to explore various outlets for one’s work, to engage on a level that blurs the distinction between purely artistic inquiry and social commentary — that can lead cinema and its practitioners back into the spotlight, a place it once inhabited and still can. Of all people, Marker should know what it takes; he was there the first time it happened.