Back to selection

Back to selection

Rotterdam 2008: Who’s Afraid of Kathy Acker?

Who's Afraid of Kathy Acker?

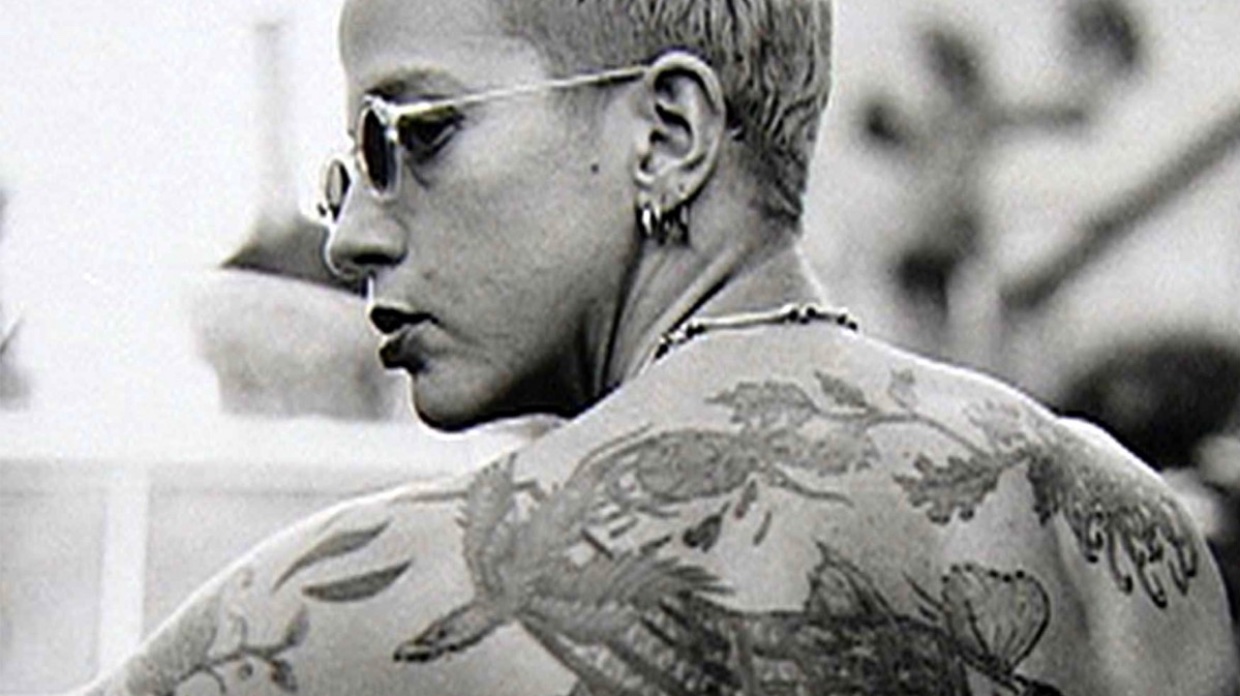

Who's Afraid of Kathy Acker? Who’s Afraid of Kathy Acker?, premiering here in Rotterdam, is Barbara Caspar’s thoughtful and creative film biography/essay on the late writer, whose formally inventive novels, published from the ’70s through the mid-90s, challenged assumptions about gender roles, sexuality, and the literary canon. A beguiling and intensely contradictory figure, Acker is best known for books which creatively appropriated texts from Great White Male writers, retelling them in an emotionally raw, sexually blunt, and politically questioning female voice. And with her appearance in several conceptual art videos in the ’70s, her close-cropped dyed blond hair, her tattoos and her piercings, Acker was also performance artist, proto riot grrl, and living link to the transgressive authors of the ’50s and ’60s U.S. and French experimental fiction scenes. Acker died of breast cancer in 1997 and now, just over ten years later, Caspar has made a film that captures the essence of both Acker the writer and Acker the person while arguing convincingly for the continuing relevance of her work today.

Caspar includes a lot of the conventions of the artist bio-doc — interviews with friends and associates, archival footage, etc. — in a film that covers in broad strokes the different eras of Acker’s life. There’s a lot here that I didn’t know, from those conceptual art videos to her quite vanilla (and short-lived) marriage when she was 20. Perhaps one of the strengths of the doc is that I didn’t think about what is left out, like some of her key relationships (her marriage to the composer Peter Gordon is not included here) and artistic endeavors (like her large-scale theatrical collaboration with Gordon, Richard Foreman, and David Salle, The Birth of a Poet) until the next day. In fact, Caspar doesn’t discuss Acker’s books with any great degree of specificity. She’s all about capturing the broad strokes of Acker’s ideas as well as conveying to the viewer the galvanizing, seductive and complicated nature of her persona. Caspar includes discussion of Acker’s attraction to sexual masochism, the plagiarism charges against her, and her willful but misguided attempt to beat cancer by rejecting Western medical treatments, refusing to allow Acker to go gently into the good night of literary respectability.

In addition to the conventions of the artist bio mentioned above, Caspar creatively employs a number of other devices which are both bold, and, I think, rewarding. She includes crudely roto-scoped animated dramatizations of scenes from Acker’s work, which play out in stark blacks, whites and reds underneath a voiceover reading Acker’s prose. Even more interestingly, she often cuts to a series of interviews with young women, who look to be from about 16 to their early 20s, discussing what Acker’s work means to them. There’s something compelling about these women and the casual way they are shot and recorded. I ran into Caspar here and asked her about these scenes, and she told me the footage comes from casting tapes she recorded when looking for actors to play the girls in the animated sequences. It wasn’t until post-production that she realized that the comments and passion of these young voices made the perfect argument for the continuing vitality of Acker’s work. (Caspar also told me that she cut a more conventional version without this material for broadcast, but that the Rotterdam version is her “director’s cut”).

I knew Acker just a little bit in the late ’80s, when I was the Programming Director at The Kitchen and Ira Silverberg, eloquent here in his discussion of her life and career, was the Literary Curator. She kindly agreed to play a philosophy professor in the first film I was ever involved with, Raul Ruiz’s The Golden Boat, although I remember her laughing that the dialogue Ruiz had written for her represented a philosophical position that she pretty much disagreed with. Caspar’s film beautifully captures the smart, funny and quite warm Acker I remembered.

There’s a great moment in the film when Acker, lecturing in San Francisco in the early ’90s, is asked what she thinks about cyber-sex. She admits to knowing nothing about it — “I like relationships and I like flesh,” she says. The question made me realize that she died near the beginning of the Internet Era and that so many of her issues, from polysexuality to new forms of literary creations, are now being explored actively online. It would have been fascinating had she lived to have seen where her work would have gone.