Back to selection

Back to selection

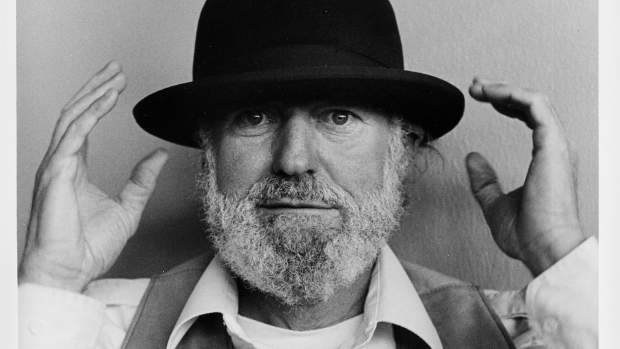

Five Questions with Ferlinghetti: A Rebirth of Wonder Director Christopher Felver

Lawrence Ferlinghetti makes a brief appearance in Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz — an appearance Christopher Felver wanted to include in his new documentary about the poet and First Amendment hero. But when Felver realized he couldn’t get the footage for what he felt was a reasonable price, he didn’t see it as a make or break moment. After all, as someone who’s been training his camera on Ferlinghetti for 30 years, Felver had plenty of raw material.

Assembled from footage shot as far back as the 1980s, Felver’s Ferlinghetti: A Rebirth of Wonder opens February 8 at the Quad Cinema in Manhattan. A son of immigrants, a World War II veteran, a friend and champion of Beat Generation icons, a publisher and owner of San Francisco’s famed City Lights bookstore, Ferlinghetti has led a life that is at once quintessentially American and wholly remarkable. Felver, a well-known still photographer, has been chronicling Ferlinghetti’s life for years, a collaboration that resulted in a 1996 documentary and a 1998 book of portraits. Speaking on the phone from his home city of San Francisco, Felver answered a few questions about his film.

Filmmaker: You made a film called The Coney Island of Lawrence Ferlinghetti in the ‘90s. How did you come to know him, and why did you start making documentaries about him?

Felver: In ’83 we went to Nicaragua and did a book called Seven Days in Nicaragua Libre. We went down for a poetry festival. I got lucky because (poet) Gary Snyder had to pull out of it, so Lawrence and I sort of started traveling then. We’ve been traveling ever since.

The first film was a day-in-the-life. There’s no one else in it. It was OK. I liked it. It played on TV around here. But obviously there was more to it. I remember seeing a biography of Hemingway, and it got very heavy into his Chicago roots. So I thought: That should be told, that part of Ferlinghetti’s story.

Filmmaker: You’ve been putting together the new documentary for about 10 years?

Felver: That’s about right, sure. Some of the stuff in there I shot in the ‘80s. I’ve been following him around for a long time. We have a good time. It’s like being with a guy you like to have a drink with. And Lawrence does like to have a drink. We went over to Ireland once, and then we went to Germany after that. And then we went to Italy, and then to Paris to see George Whitman (the late owner of the famed bookstore Shakespeare and Company). That was Lawrence’s best friend, period.

Filmmaker: In 1956 Ferlinghetti published Allen Ginsberg’s Howl, which was being called “obscene” at the time. The importance of freedom of speech is one of the big themes in the film. Is that one of the takeaway messages you’d like people to get from your film?

Felver: Yeah, I’m political. Freedom of speech is still the big one. Lawrence risked everything on freedom is speech, like everyone says in the film. Howl, that was pretty risky territory back then. That was a seminal case. What a contribution, right?

Filmmaker: When we first got on the phone you were telling me about The Last Waltz. What’s the story there?

Felver: That’s the one thing that’s not in there. We couldn’t afford it from Warner Bros. They wanted $12,000 for two years. I said, “For two years? What happens after that?” (A Warner Bros. representative) said, “After that we’d have to renegotiate.” Letters to Scorsese never got past his secretary. That was really disappointing. We got stonewalled.

Filmmaker: There’s a scene in your film — it looks like it was shot fairly recently — where we see Ferlinghetti riding his bike to City Lights. He’s 93 years old. How is he doing these days?

Felver: I had lunch with him yesterday. I mean, he’s something else. He really is. He’s still 100 percent sharp. You couldn’t put anything by him. He’s very proficient on a computer. He’s not in perfect shape, but I think he’ll be around for a while longer. Let’s hope he makes it to 120. We need people like him.