Back to selection

Back to selection

Of Tarantino and TV: The Legacy of Goodfellas

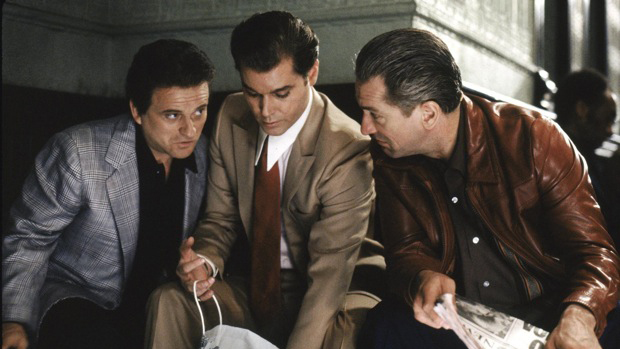

Joe Pesci, Ray Liotta and Robert De Niro in Goodfellas

Joe Pesci, Ray Liotta and Robert De Niro in Goodfellas In the mid-1980s, Martin Scorsese was regaining his footing as a director after a brutal few years. His passion project, The Last Temptation of Christ, had fallen apart at Paramount just days before production was scheduled to begin, and The King of Comedy had been a commercial, and largely critical, failure – in spite of the fact that it was, and is, one of the most incisive films ever made about celebrity culture. After years of working on studio movies with substantial budgets and luxurious schedules, Scorsese went back to ground zero for After Hours in 1985, stripping his methods down to the bone in order to prove to himself and everyone else that he still had what it took – like the hero of Raging Bull, you couldn’t keep him down.

Following After Hours, Scorsese returned to traditional studio filmmaking for The Color of Money, a sequel to The Hustler designed to reestablish Scorsese as a commercially viable director (which it did). It was while shooting that picture in Chicago that Scorsese came across Nicholas Pileggi’s Wiseguy, a journalistic account of the rise and fall of New York mobster Henry Hill. A mid-range gangster who never got “made,” Hill went into witness protection after spending decades in the mob and then testifying against his friends to save his own skin; along the way he gave Pileggi hours of interviews that formed the basis for a riveting street-level account of day-to-day life in the world of organized crime.

Scorsese, who had documented the lives of low-level criminals in Who’s That Knocking at My Door and Mean Streets, felt an immediate affinity with Pileggi’s characters and knew he wanted to document them on film. As serendipity would have it, his old friend Irwin Winkler (the producer of New York, New York and Raging Bull) held an option on the property, so Scorsese and Pileggi teamed up to write the screenplay, with Winkler on board to produce. It was supposed to be Scorsese’s follow-up to The Color of Money, but when an opportunity arose to finally make The Last Temptation of Christ, Scorsese took it and put Wiseguy (the title would eventually be changed to Goodfellas) on hold. Then, he returned to the project, and got down to the business of making one of the greatest American films of all time.

It was a seminal work for Scorsese as well as for American movies in general, both summing up everything the director had done before and pointing the way toward the ambitious epics to follow. It serves as both the final film in one trilogy (Who’s That Knocking at My Door, Mean Streets, Goodfellas) and as the first film in another (Goodfellas, Casino, The Wolf of Wall Street). It’s the transitional movie in which Scorsese crystallizes several of his obsessions, leaves others behind, and finds his new, great subject that would define all of his best films to come: the corrosive effects of rampant materialism on the soul.

The soul, of course, has always been of paramount importance to Scorsese, a director who wears his Roman Catholicism on his sleeve and once entertained the notion of becoming a priest. In Who’s That Knocking and its unofficial sequel Mean Streets, the protagonist played by Harvey Keitel is tormented by the tensions between what he learns in the church and what he lives on the street. He’s a relentless sinner plagued with guilt who desperately seeks redemption, even though he’s often unaware of the contradictions between his actions and his beliefs. He’s trying, though – something that cannot be said of the characters in Goodfellas. By the time Scorsese gets to them, the guilt and redemption are gone — it’s all sin. For nearly 2½ hours, Henry Hill (Ray Liotta) and his friends (Robert De Niro, Joe Pesci) rob, beat, and kill without a moment of contemplation or remorse; one of the movie’s many great ironies is that it has constant voice-over narration by a guy who is not remotely reflective or self-aware. Henry doesn’t even feel bad about ratting out his friends – he just feels bad that after a life of crime he’s demoted to living the kind of middle class suburban life to which millions of Americans aspire.

Goodfellas is the first of many Scorsese masterpieces to explore both the undeniable appeal and the moral suffocation of accumulating material goods. A key scene in both the film and Scorsese’s oeuvre as a whole comes when his camera glides across the inventory of Henry and his wife Karen’s (Lorraine Bracco) closets while Henry stuffs cash into his pants for no reason that’s ever explained. Karen asks him for some shopping money and he gives her a wad of bills just before she drops to her knees and unzips his pants. While Scorsese isn’t saying that Karen is a prostitute, he is creating connections between money and a certain kind of eroticism that will reach full flower in Casino and The Wolf of Wall Street. “Love costs money,” Ace Rothstein (Robert De Niro) tells us in Casino just before he proposes to prostitute Ginger (Sharon Stone) in a film that uses Las Vegas to trace the moral decline of capitalism in the late 20th century. The Wolf of Wall Street is a three-hour bacchanal packed to the edges with strippers and prostitutes, women who in Scorsese’s universe become the ultimate logical extensions of capitalist excess; they’re seller and sold all in one.

Goodfellas, Casino, and Wolf are all about characters driven by consumption; no director has ever photographed expensive clothes, food, and domiciles more lovingly than Scorsese, or documented their moral vacancy more chillingly. The seductive appeal of what money can buy is brilliantly captured in Goodfellas’ justly celebrated Steadicam shot that follows Henry and Karen from the street through the VIP entrance of the Copa nightclub and to their lavish front and center table. This isn’t just a director showing off, it’s a distillation of why one character would be willing to sell his soul for this lifestyle, and why another would be willing to look the other way while it happens. Scorsese repeats the device in Casino for a Steadicam shot that follows a gangster with a briefcase as we learn how the mob skims money from the casino; the shot’s subject is literally the movement of money, something The Wolf of Wall Street develops into an entire subplot. Even a superficially genteel film like The Age of Innocence fits in with this overall sensibility, as Scorsese dwells on the pricey homes and place settings to hammer home the point that Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) would rather live with heartache his whole life than go after the woman he loves and leave his upper class lifestyle.

Age of Innocence is, like Goodfellas, one of Scorsese’s great anthropological studies of a subculture. He had touched on this before in movies like Mean Streets and The Color of Money, but the breadth and precision of detail in Goodfellas marked a major leap forward in the director’s development. The movie is jammed to the hilt with descriptions of everything from prison life and pasta sauce to methods of hijacking and the ways a mob boss makes his phone calls; this sense of journalistic detail was the greatest gift Pileggi’s book gave Scorsese, and once the director figured out how well he took to it as a cinematic device he never let go of it again. His films after Goodfellas are exquisite accumulations of social, cultural and historical rituals, so densely layered that many of them (Gangs of New York, The Aviator, The Departed, Wolf) run a solid three hours or so. Yet they never feel excessive in their length, because Scorsese’s sense of visual and narrative concision makes the most of his running times; this too was pioneered in Goodfellas, where Scorsese figured out how to use a combination of radical editing techniques and voice-over narration to stuff as much information as humanly possible into his frames.

If Goodfellas was a turning point for its director, that goes double for his many disciples, who made it one of the most imitated films of its era. Its impact was immediate; unlike other now iconic pictures such as Blade Runner, De Palma’s Scarface or John Carpenter’s The Thing, Goodfellas’ greatness was acknowledged almost immediately by almost everyone. There were a few naysayers, like one-time Scorsese champion Pauline Kael (who acknowledged the film’s stylistic prowess but found it dramatically flaccid), but a surprising number of critics, starting with the massively popular Roger Ebert and Gene Siskel, were willing to go on the record calling it one of the greatest movies ever made. Audiences loved it too, making it Scorsese’s biggest hit to date next to The Color of Money; I was able to see it eleven times during its initial release without breaking a sweat because it stayed around so long.

Before Goodfellas, Scorsese was beloved without necessarily being hugely influential. He certainly had his imitators (like Phil Joanou, whose excellent Irish-American Mean Streets riff State of Grace opened just five days before Goodfellas), but one could imagine the pre-1990 American cinema as a whole not being significantly different if Scorsese had never appeared on the landscape. One could not say the same after 1990. Only two years separated the releases of Goodfellas and Quentin Tarantino’s Reservoir Dogs, a film whose attitudes and dialogue are unimaginable without Scorsese and Pileggi’s antecedent. Two years after that, Tarantino would make Pulp Fiction, a self-conscious homage to and commentary on Goodfellas (and a lot of other movies) that was to Scorsese’s film what Godard’s early pictures were to American crime flicks and musicals.

Pulp Fiction’s massive popular success brought Scorsese’s innovations into the mainstream for a few years, as filmmakers like Barry Sonnenfeld (Get Shorty) and Steven Soderbergh (Out of Sight) took advantage of the newfound freedom to present morally ambiguous characters in big studio movies, and in Soderbergh’s case, to play with conventional notions of cinematic storytelling. Like Goodfellas, Out of Sight throws out the “rules” of screenwriting structure to jump around in time and uses self-conscious freeze-frames, jump cuts, and other expressionistic editing devices to provide both ironic distance and a more sensory emotional experience. Soderbergh, a longtime Godard disciple, didn’t necessarily need Scorsese to teach him these devices, but he needed him to make them acceptable forms of expression in the eyes of audiences and studio executives.

That’s what Goodfellas did. Scorsese and his generation were enamored of Godard, Truffaut, and their contemporaries right from the beginning, but it took Goodfellas for the revolutions of the French New Wave to truly infiltrate large-scale studio filmmaking. Throughout the 1990s, the sense of cinematic liberation engendered by Scorsese’s masterpiece would yield experiments of a type unthinkable in a pre-Goodfellas Hollywood – Molotov cocktails like Oliver Stone’s Natural Born Killers and David Fincher’s Fight Club, and the Hughes Brothers’ heavily Scorsese-influenced Dead Presidents (a scathing critique of American power structures released by Disney – did such a time really exist?). It would also produce a series of pop epics like American Hustle, Blow, Summer of Sam, and Boogie Nights that used Goodfellas as a virtual template. Boogie Nights in particular owes an enormous debt to Scorsese’s film, as director Paul Thomas Anderson begins with a bravura tracking shot that combines two of Goodfellas’ signature long takes: the introduction of all the members of Paulie’s gang in one shot, and the Steadicam journey through the Copa. Anderson then proceeds to tell a story no less elegiac and nostalgic in its depiction of a changing era than Scorsese’s tale, and no less beholden to popular music and unorthodox narrative structure.

While Goodfellas’ influence on contemporary cinema is immense, its effect on television cannot possibly be overstated. The new “golden age” of TV represented by Breaking Bad, Mad Men, and others simply would not exist without Goodfellas. That’s because none of those shows would exist without The Sopranos, a series that broke new ground in television by absorbing Scorsese’s film into every molecule of its DNA. From its casting choices to its production design to its use of music to its anthropological observations to its sense of humor and beyond, David Chase’s landmark program borrowed extensively from the Goodfellas playbook. As played by James Gandolfini, the brutal, racist, and misogynistic Tony Soprano would have fit right in in Scorsese’s world, where those characteristics coexist with a skewed sense of loyalty and family values. Chase’s innovation was to develop these contradictions over the course of six seasons to create a rich tapestry of hypocrisy that infected everyone who came into Tony’s orbit – FBI agents, therapists, even Ben Kingsley playing himself! – and generate a caustic satire on post-9/11 America almost as harrowing as Scorsese’s own The Departed.

The Sopranos established the prototype for a new kind of male antihero on television, with its overtly masculine protagonist slowly eroding under the contradictions of his own flawed and no longer sustainable moral code. Vic Mackey on The Shield, Walter White on Breaking Bad, Mad Men’s Don Draper, Tommy Gavin of Rescue Me…the list goes on and on. Without Goodfellas and Henry Hill, you have none of these men and none of these shows – and you probably don’t have Six Feet Under, or Homeland, or any number of other programs that the success of The Sopranos made possible. The moral ambiguity that all of these shows have in common is perhaps Goodfellas’ most penetrating legacy, and the logical outgrowth of its most prescient insight. Scorsese and Pileggi knew something in 1990 that the rest of us weren’t quite ready to accept or articulate yet (and based on some of the critical backlash against Wolf, some people still aren’t): that the American Dream as it once existed mutated into something monstrous without us even realizing it. By the time of Casino, the game was literally rigged, and in The Wolf of Wall Street there isn’t even a pretense that one can succeed in the system as it currently operates without selling one’s soul.

The only thing more unsettling than the convincing force with which Scorsese drives home this idea is how fun he makes selling your soul look; he’s been criticized for glorifying his gangsters as well as Jordan Belfort, and let’s be honest – their lives look a lot more desirable than that of the noble but exhausted Frank Pierce (Nicholas Cage) in Bringing Out the Dead. But Scorsese’s refusal to pass judgment or direct his audience to do so is his greatest provocation and his greatest achievement. After a decade in which the American cinema was largely characterized by its complacency in the form of movies like Rambo and Top Gun that showed us how great we all were, Goodfellas served as a necessary challenge to conformity (both political and stylistic) and inspired Hollywood movies to grow up again – at least for a while. It didn’t last, but then, as Henry Hill himself knew, the glorious times never do.

Goodfellas closes the Tribeca Film Festival this Saturday. More information on the screening here.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and iTunes. He also hosts a monthly podcast series on the American Cinematographer website and serves as a programming consultant at the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles.