Back to selection

Back to selection

Little Things Mean a Lot: Alex R. Johnson’s Two Step

James Landry Hebert and Skyy Moore in Two Step

James Landry Hebert and Skyy Moore in Two Step A visibly irritated, middle-aged leader of a small-town criminal syndicate lectures a younger, much more junior member of his band of thugs. The latter has just informed him that he might be able to rustle up a portion of the 10 grand he owes him over the next few days. “I don’t live in a $10,000 world of maybes, Webb,” says the boss, Duane (Jason Douglas). I live in Texas.” (The troubled and troubling sociopath Webb is played by James Landry Hebert, a man who will be going places.) Don’t look for logic in the sage’s upbraiding.

The statement is an assertion of (mostly mythological) honor, of the importance of keeping one’s word in a unique subculture that lacks flexibility and often invents rules to accommodate some powerful citizen’s mandate. One of the more popular tunes we who grew up there sang about the state, “Deep in the Heart of Texas,” is a joyous if unsophisticated testament to its variety and abundance. Every other line is a refrain of the title in case you missed the point that Texans are a proud bunch.

Along comes a Yankee named Alex R. Johnson, who ensconces himself in the thriving film community in Austin and makes a few music videos and produces a few shorts. Almost everyone else involved in the production of his sleeper genre remix Two Step is a native Texan. The collaboration of an outsider writer/director — you will never qualify as an insider had you not been born there — and a team of Texans has produced a film with a new spin not only on Austin (the characters are far from the eccentric but innocuous slackers in Linklater’s work, and the backdrops here are mobile homes in socio-economic zones far below the average Slacker level) but on the thriller genre itself.

Two Step rips even more deeply into the heart of Texas than does that old standard melody. It raises to the surface the scars and disease that have eroded whatever senses of modesty, propriety, and reciprocal respect still remain. (Just to mention that Johnson brilliantly plants anticipatory seeds in just the right spot in his screenplay, small items that will ultimately bear significance.)

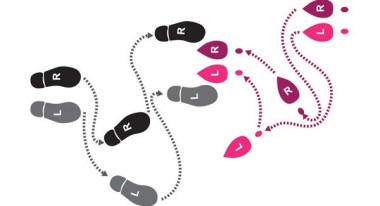

The principal characters are revealed mainly by their contact with others. Like in the Duane-Webb scene noted above, they come in pairs. Two Step is an ideal title. The old country dance movement (quick, quick, slow, slow) requires a leader and a follower. Its gliding motion can be reworked to be more or less suggestive or embracing. And, as luck would have it, “two step” also means evading responsibility, whether in politics or just big problems. The regroupings enable a moody re-genre-ation, sometimes very surprising but always consistent with the overall narrative.

Warmly vulgar (“Eat me!”), affectionate (everyone is called “Sugar”), and quick-tongued, Dot (an appealing lightning bug called Beth Broderick), a thrice-married ex-ballerina and barfly who teaches two-step and other country dances at schools and institutions in the Austin area, is the emotional center of what otherwise would be a relentlessly misanthropic, violent film (even if Johnson keeps the violent acts off-screen, concentrating more on the extended pain of the victims).

Dot’s savvy ripostes save her in this machismo-drenched environment. Charisma-challenged and married, her cop friend, Horace (Barry Tubbs), is a poor excuse as an occasional romantic partner. When she whines, “I’m not a spring chicken anymore,” he tactlessly remarks, “But you’re built like a bottle of Coke!” Potentially fulfilling her maternal instinct, however, is recent Baylor dropout James (Skyy Moore), a naif whose grandmother passed just after he arrived from El Paso for a visit. (Grandma and Dot were friendly neighbors.)

The “James” and “Webb” strands are isolated for nearly half of the film, but when they do intersect, the whole tenor of Two Step changes. Webb’s girlfriend, Amy (Ashley Rae Spillers), has shacked up with Duane while her guy was serving out his prison time. The rejection and betrayal send Webb far over the edge, although he appears most concerned when he discovers that she has withdrawn all of their money. Poor James was in the wrong place at the wrong time: His grandmother had been a victim of the so-called grandparent scheme, in which young people prey on the forgetfulness of the elderly to insinuate themselves not so much in their lives but in their bank accounts.

According to Johnson in the press notes:

I wondered about the actual grandkid, the one the conman pretended to be. What do they think when they hear about it? When they realize their disconnect or lack of a relationship has aided and abetted the con?

And from an article in Brooklyn Vegan:

There is a special emptiness that surrounds you in the moment your family is gone and it opens you up to all manner of hardship as you drift through it. “Two Step” begins in this moment and I wanted to write something that played at the fog that follows….

Once the two story lines crisscross, the homicidal, manic Webb attempts to escape to Mexico, while much more quietly James tries to reach the knife in the pocket of one of Webb’s victims to untie himself and take control — to revise the ground plan and move from follower to leader of his two-step dance with Webb.

Johnson uses numerous signifiers to evoke Texas and sustain the thriller/noir cross-fertilization (gas pumps, eerie wind chimes, armadillos, rows of crows on telephone wires — perhaps silent witnesses and homage to Hitchcock at the same time — and of course, the Texas flag, repeatedly). Formal strategies that help convey the mood include close-ups held long on odd objects, voiceover, frequent cross-cutting and dramatic ellipses—ones which bypass significant scenes.

The two-step pattern extends to creators behind the camera. Johnson was heavily involved with Andrew Kenny in the composing process. The brilliant score by the frontman for American Analog Set and Wooden Birds keeps things at a low, frightening hum; he often just strums a guitar. He also plays solo piano for the marvelously melancholy “Long Time To Lose It” that accompanies the final credits. Austin provides several country singers such as Laura Cantrell and Whiskey Shivers. My favorite titles are “Tall Walkin’ Texas Trash” and “Kitty Wells Dresses.”

Johnson also worked closely with editor Benjamin Moses Smith (who does a great job of shifting back and forth among the tales) and with d.p. Andy Lilien, who has a superb method for capturing colored lights inside cheap bars that manages to lift the ambience without dismissing the places as merely tacky.

I have seen some festival reviews that call the ending “abrupt.” Can I just say, it is the conclusion par excellence, an ambiguous but suggestive topper to all that has preceded it. It is literally “heavenly,” just the right counterpoint to the slimy people and sets we have encountered for an hour and a half. Alex Johnson, you lived in Washington and New York as a child, settled in Brooklyn for 18 years, and then carpetbagged to Texas. I think you will be moving on, or possibly advancing in the city where you have planted roots, but to see that someone can create so masterfully a debut feature makes me wish that I were a mogul. Not true — but it does increase the joy of writing reviews.