Back to selection

Back to selection

2010 Cannes Film Festival | By Livia Bloom

“You know the kind of movie where people laugh and cry?” asked a filmmaker character in Kornél Mundruczó’s Tender Son: The Frankenstein Project (seeking American distribution). “I want you to cry.” “I am crying,” responded the would-be actor before him, his face frozen solid. The internalization of emotion, and the tiny, subtle ways it can creep into the features and postures of even the most stoic characters was explored in some of the best work at this year’s Cannes Film Festival.

At first glance, the protagonist of A Screaming Man (pictured above) (Un homme qui crie, seeking distribution), by the talented Chadian director Mahamat-Saleh Haroun, looks less like a man screaming than a man lounging. Champion (played by Saleh Haroun) hangs out with his teenage son in the pool of the posh hotel where they work, feeds watermelon to his wife till juice drips from her chin, and knows all his neighbors by their nicknames. At night, he does sit-ups on a plastic mat outside his home until he can do no more; then a pause; then he begins again. When this former swimming ace loses the job that defines him, emotional hurt barely registers on his placid surface. Only gradually do his actions, set against the backdrop of his country’s political strife, begin to belie the startling ferocity of his true response and the disastrous ripples of its consequences.

Although not one female director was selected for the Official Cannes Competition this year, it was a great year for female performers. Several actresses did yeoman’s work, backwards and in heels. In Lee Chan-dong’s Poetry, which won this year’s prize for Best Screenplay and has happily been acquired by Kino International, Korean actress Yoon Jung-hee carried the weight of a 139-minute opus on her thin frame. As Mija, an aging working-class maid raising her grandson in a small town, her character is at once modest and tragic, eccentric and proud. She holds her responsibilities very quietly, even when they become nearly unbearable. In Mija, these qualities are communicated in the smallest of ways; they are there in the way she wears her clothes, in the slight inclination of her head, and the slight stoop of her shoulders.

Certified Copy, the much-anticipated new film from director Abbas Kiarostami (IFC Films now holds the US rights), divided audiences as to whether its strength lay in the existential abstraction of a romance, or the scholarly examination of artistic authenticity. (This line of inquiry provides the film’s ironic title.) “The garden of leaflessness: who dares to say that it isn’t beautiful?” asks one character, questioning the subjectivity of beauty, while another wonders whether even an “original” painting is anything more than a copy of a once-living model’s original smile. Although the jury preferred the film’s more interpersonal aspects and gave Juliette Binoche the prize for the Festival’s Best Actress, my vote was in favor of the film’s script and its more academic concerns. Certified Copy is Kiarostami’s first outside his native Iran, and his first using a European cast, circumstances which sparked public debate about its authenticity as a “true” or “certifiable” Iranian film long even before its Cannes premiere.

The Lips (Los labios, seeking American distribution), an Argentine film written and directed by Iván Fund and Santiago Loza, took a measured, respectful approach to the work of three social workers, less played than inhabited by Victoria Raposo, Eva Bianco, and Adela Sanchez, three actresses who were recognized for their work with a shared Certain Regard Special Prize. In the film, they travel through the impoverished countryside surveying the needs of locals and cataloguing their medical and familial status, uncomplaining despite less-than-luxurious circumstances. The naturalistic central performances offer a humanistic, resourceful way of approaching the world, while the immediacy of María Laura Collaso’s camerawork give the film a quiet, documentary-like quality. With little fanfare, the trio depicted in The Lips contributes to their community one little person at a time.

The selection at Cannes never shies away from films that draw connections between the personal and the explicitly political. This year, a satisfying late addition to the Competition came in the form of Ken Loach’s Route Irish (seeking American distribution), an accessible, deceptively-straight forward thriller about a military defense contractor named Fergus, played with silent conviction by the British actor Mark Womack. With years of military training and experience in the Middle East behind him, Fergus launches a personal investigation into a shooting on Route Irish, the road to the Green Zone, which sent his best friend home from Iraq in a body bag. The film makes excellent use of the myriad texts, emails, and artifact-scarred videos that now form the connective tissue between loved overseas. Past events from Iraq gradually trespass on Fergus’s peacetime present in a manner reminiscent of the Holocaust memories that infiltrate Rod Steiger’s consciousness in Sidney Lumet’s The Pawnbroker (1964). Yet the horror articulated in Route Irish distinctly belongs to contemporary world events. One set piece depicts the brutal extraction of a confession, a decision made at what is projected to be an incredibly high price. Yet in the final tally, that price comes in far higher than its Decider ever dreamed possible.

Radu Muntean’s Tuesday, After Christmas (Marti, Dupa Cracuin, seeking distribution) is a portrait of a threatened marriage that is as devastating as the events it depicts are mundane. Its characters are recognizable, and its story feels both unpredictable and inevitable. The selection and execution of the discrete scenes through which the film unfolds make it every bit as effective as recent, seemingly understated Romanian films like Cristi Puiu’s The Death of Mr. Lazarescu (2005), Corneliu Porumboiu’s Police, Adjective (2009) and Christian Mungiu’s 4 Months, 3 Weeks, and 2 Days (2007). Of this film, Ingmar Bergman, patron saint of disintegrating relationships, would undoubtedly approve.

Every year, the restorations that premiere in the Cannes Classics section of the festival are some of the strongest, most compelling films on offer. The understated emotion that marked many other characters at this year’s festival carried over into works like Mest (Revenge, Kazakhstan, 1989) by Ermek Shinarbaev, the story of a young Korean boy who was conceived in order to avenge his sister’s death. The Eloquent Peasant (Shakavi el Flash el Fasi) is a short film that uses tableaux-like compositions to tell the ancient story of a peasant who is robbed and then unfairly accused of theft. It was made in 1969 by Shadi Abdel Salam, the wildly gifted Egyptian director of The Night of Counting the Years (Al Momia, also 1969). For the availability and restoration of these films, thanks are owed Martin Scorsese, Kent Jones, and their work at the World Cinema Foundation. In collaboration with the Cineteca di Bologna/L’Immagine Ritrovata Laboratory, they brought these films to Cannes, along with Two Girls on the Street (Két lány az utcán, Hungary, 1939) by André De Toth, and A River Called Titas (Titas Ekti Nadir Naam, India-Bangladesh, 1973) by Ritwik Ghatak. While many of the other films from Cannes await the uncertain prospect of international distribution, the World Cinema Foundation is also the distributor of the films they restore. Film programmers may contact them to book screenings of their films, and home viewers eagerly await the release of their titles in DVD form through their new collaboration with the Criterion Collection.

An enthusiastic crowd gathered on the beach for a screening of another sort of classic: Le Monde du Silence (The Silent World, 1956) by Jacques-Yves Cousteau and Louis Malle. A strange filmic artifact to be sure and an ancestor to today’s popular “nature documentaries,” the film depicts Cousteau in action, the very model of the then-modern undersea adventurer. The film held viewers of all ages entranced with whale sightings and shark attacks, rides on giant-sea turtles, and the discovery of a sunken vessel in all its murky, barnacled glory.

Also on the lighter side were two particularly over-the-top cinematic confections: Gregg Araki’s candy-colored, self-possessed and super-sexed Kaboom, which played in a midnight screening, felt like an episode of the Power Rangers crossed with The Hills; or, during its darker moments, the famous Bat for Lashes video for the song “What’s a Girl to Do?” Kaboom, winner of the inaugural Queer Palm Award, will be brought stateside by IFC Films. The thriller Black Heaven (its French title is L’Autre monde, literally The Other World) from the French director Gilles Marchand was another enjoyable midnight movie (seeking American distribution). Chiaroscuro animated scenes drew viewers along with the film’s protagonists into a Second Life-like videogame that exerted a melancholic, hypnotic pull.

A far subtler other-world beckoned in the Palme d’Or-winning film from this year’s Cannes Film Festival, Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives (seeking American distribution). Its director is Apitchatpong Weersethakul, a Thai filmmaker who was trained in the US and allows himself to be called Joe (by those not-so-fleet-of-tongue). He is beloved by the film community for challenging, magical films like Mysterious Object at Noon (2000), Tropical Malady (2004) and especially Syndromes and a Century (2006). The latter film drew on family lore—the legend of the director’s parents’ meeting—and depicted this tale with the surprisingly casual intersection of specters from the past with living characters from the film’s present. Silimarly ruled by dream logic rather than conventional cinematic grammar, Uncle Boonmee’s win at Cannes was widely viewed as a happy victory for modesty and artistic integrity in international cinema.

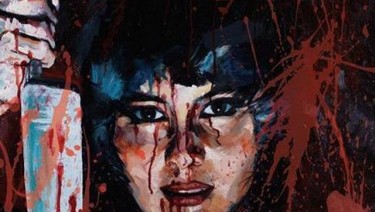

Common wisdom dictates that the best films are always shown in one of Cannes’ carefully curated sections, with Director’s Fortnight (Quanzaine de Réalisateurs) and Critic’s Week (Semaine de la Critique) showing new films not included in Official Competition, Out of Competition, or Certain Regard. Yet it can also be a good idea to venture into the uncharted waters of the Marché du Film (Film Market), where a wild profusion of movies are for sale. There, with a little luck, you might happen upon a gem like Ho Cheung Pang’s Dream Home (seeking American distribution) one of the strongest horror films of the last several years. This blood-soaked caper from Hong Kong doubles as a satirical look at the housing and banking crises that have crippled markets around the world. When it comes to getting her ideal apartment, the girlish Sheung (Josie Ho) seems like any other aspiring yuppie. But like many of the other characters that graced screens in Cannes this year, there’s a dark side to this seemingly serene protagonist. When you least expect it, still waters run deep.