Back to selection

Back to selection

Silent Running, Year of the Dragon and Rolling Thunder Revue: Jim Hemphill’s Home Video Recommendations

Year of the Dragon

Year of the Dragon When Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda’s Easy Rider grossed somewhere around 120 times its cost in 1969, the Hollywood studios took notice and began scrambling to find their own Easy Riders, and their own Hoppers and Fondas. Universal executive Ned Tanen’s approach was to start a division that would give young filmmakers creative control provided they stuck to a one-million-dollar budget; the idea was that at that price Universal couldn’t really lose much, but if just one of the movies broke big it would pay for the rest and then some. The experiment yielded several very interesting films, including Fonda’s The Hired Hand, Milos Forman’s Taking Off, and Monte Hellman’s Two-Lane Blacktop. (Though none of these fulfilled Universal’s desire for an Easy Rider-sized hit, Tanen did eventually strike gold with George Lucas’ American Graffiti at the tail end of the cycle.) One of the most original movies in the series was the 1972 science fiction picture Silent Running, which marked the directorial debut of special effects wizard Douglas Trumbull following his stunning work on 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Andromeda Strain. The movie looks forward to intimate character-driven sci-fi films like Moon and High Life with its story of a botanist (Bruce Dern) traveling through space in a sort of floating greenhouse that he’s determined to protect at all costs, but the vast number of imitations have done little to dilute Silent Running’s intelligence and power. The fact that Trumbull made it for a million bucks, even in 1972 dollars, is astonishing and a testament to his effects expertise as well as some resourceful location work (most of the movie was shot on a decommissioned aircraft carrier that the production rented for peanuts). The new Blu-ray from Arrow Video is a feast for Trumbull enthusiasts like myself who want to dive into his process, with multiple commentary tracks and hours of making-of documentaries, both vintage and contemporary. There’s also a great visual essay by Jon Spira that examines the evolution of Silent Running’s script, which was written by future Deer Hunter scribes Deric Washburn & Michael Cimino (credited here as “Mike”) and eventual television megaproducer Steven Bochco (credited as “Steve”).

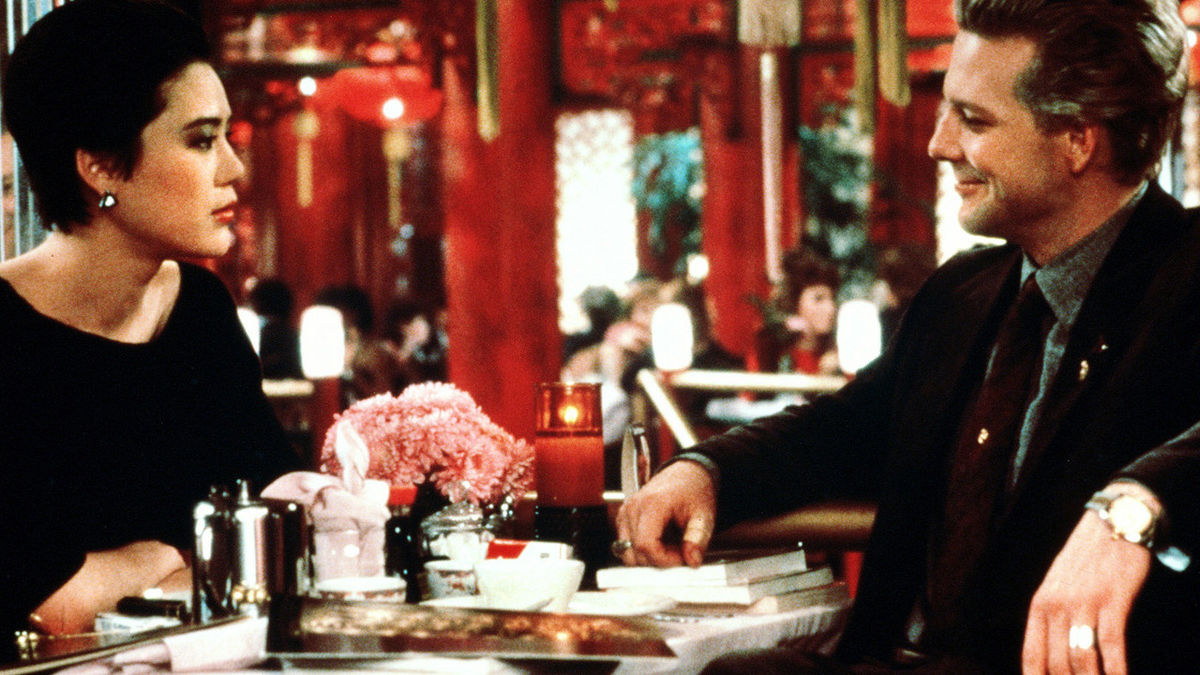

Unsurprisingly, the film was much darker in the Washburn/Cimino incarnation, with the warmer Bochco brought in to lighten things up. For a more undiluted shot of Cimino intensity, I highly recommend Imprint’s limited edition Blu-ray of Year of the Dragon (1985), Cimino’s profane and riveting return to the director’s chair after a five-year hiatus following Heaven’s Gate. Cimino had recently been fired off of Footloose (!) when he got a shot at redemption in the form of Robert Daley’s novel about a New York cop taking on the Chinese mob; working with co-screenwriter Oliver Stone, Cimino turned Daley’s procedural into a hyped-up fever dream of racial and sexual tension, casting Mickey Rourke as a bigoted, womanizing Vietnam vet fueled by resentment. Given the primal force with which Cimino directs the film (one of the era’s several great American movies about obsessive law enforcement personnel alongside To Live and Die in L.A. and Manhunter), it’s hard not to read autobiographical impulses into Rourke’s character; aggrieved and lashing out at everyone around him, he comes across as Cimino’s id during a period when the director surely felt that Hollywood had abandoned him. Rourke’s alienating characterization and Cimino’s fierce commitment to his protagonist’s point of view led many critics to charge the film with the same racism and sexism exhibited by its leading man, but I think Year of the Dragon is doing something closer to Taxi Driver, dissecting and depicting its ugly attitudes rather than endorsing them. Cimino is a less controlled filmmaker than Martin Scorsese, however, which is both a drawback and Year of the Dragon’s greatest strength. It’s a gloriously messy explosion of meticulous visual design and grand melodrama, beautifully crafted but always in danger of veering into ridiculousness – and at times stepping over that line, especially in the peculiar scenes between Rourke and his ostensible love interest. It was a rushed production by Cimino’s standards, and the speed with which he was forced to write, shoot, and edit the film is evident in its many underdeveloped subplots and egregious continuity errors. Yet the pressure Cimino was under also gives Year of the Dragon a kinetic dynamism that would be the envy of any action director – it’s a movie by a guy with something to prove, and boy does he ever. Imprint’s Blu-ray contains both a vintage commentary by Cimino and a new one by critic Peter Tonguette, as well as two brand new interviews: one with Daley and another with composer David Mansfield, a frequent Cimino collaborator whose bold score is one of Year of the Dragon’s many pleasures.

Mansfield also plays a role in my final recommendation this week, Scorsese’s 2019 documentary Rolling Thunder Revue – as does Joan Baez, who performed the songs in Silent Running. Mansfield and Baez – and Joni Mitchell, Roger McGuinn, and a slew of other musical notables – were part of the revue of the title, a tour led by Bob Dylan in 1975 and 1976 in which he tried to reconnect with his audience via small venues. Rolling Thunder Revue plays more or less like a straight documentary about the tour, but clues to Scorsese’s playfulness with the format appear throughout the film; how soon the viewer catches on will depend on one’s familiarity with pop culture history, though for movie fans Michael Murphy’s appearance as his fictional creation Jack Tanner is a dead giveaway that the director is not to be trusted, if one hasn’t caught on already. Scorsese doesn’t differentiate between the fictionalized elements of the film and the truth, and neither does Dylan – in his interviews he plays along, commenting on made-up stories told by Sharon Stone, who claims to have been on the tour as a young model, as though they actually happened. To be fair, Scorsese lets us in on the game in film’s opening, in which he presents silent footage of a magic trick from the early days of cinema; he’s telling us right off the bat not to trust him, which, as novelist Dana Spiotta notes in her liner notes for the Criterion Blu-ray release, actually makes him more trustworthy than documentarians who pretend to be presenting some kind of objective truth. What ensues is a meditation on fakery and performance in myriad forms, as well as on the slippery nature of memory and how we use it to serve present-day purposes (emotional and otherwise), though to use a somber word like “meditation” in reference to this ebullient, hilarious film feels a little odd. I’ve seen few films that better capture the joy of performance (Scorsese’s own The Last Waltz comes close), and Criterion’s new Blu-ray is the best possible means by which to share in that infectious joy. Some might hesitate to shell out the dough for a disc of a movie readily available on Netflix, but leaving aside Criterion’s superb extra features (like great interviews with Scorsese and editor David Tedeschi), the Blu-ray is essential given the spectacular DTS-HD Master Audio soundtrack – the only proper way to immerse one’s self in the sonic glories of this masterpiece.

Jim Hemphill is a filmmaker and film historian based in Los Angeles. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.