Back to selection

Back to selection

TRIBECA CRITIC’S NOTEBOOK #2: NEIGHBORHOOD WATCH

And like that it was gone.

And like that it was gone.

Funny thing about film festivals — no one seems to really miss them when they’re over, although within the provisional community that pops up during such events, no one seems to be able to talk about much else (except what they’d rather be doing). So it was with the 11th Tribeca Film Festival, which came to a close on Sunday. Even at the party for The Fourth Dimension, perhaps the most undeniably hip film in the selection (Vice! Grolsch!), the mood was sort of dutiful. As for the actual film, I, like many, left after the Harmony Korine short; I just wanted a gander at Val Kilmer’s practiced, winking crazy, and the experience left me truly sated.

This year, Tribeca’s lineup was revelatory at times, underwhelming at most others, and politically-tinged issues summoned up by the films were perhaps bigger stories than the films themselves. Whether it was the disappearance of two of the stars of Lucy Mulloy’s Una Noche or the uproar concerning Brookfield Properties’ continued sponsorship of the festival, storylines emerged that had little to do with filmmaking. (The disappearance in Miami of fest-bound Cuban national Javier Nunez Florian, who shared the best actor prize with his attending castmate Daniel Arrechega, makes him likely the first missing person to win a prize at a significant American film festival). And what was Tony Manza, the Brooklyn yoga instructor/amateur actor who, without gun training, killed a deer out of season and on camera in Ben Dickinson’s critically lauded, morally dubious, upstate-New-York-in-the-post-apocalypse picture, First Winter, thinking? Or Mr. Dickinson and his producers for that matter? The New York State Board of Environmental Conservation has some questions, many thanks. Mr. Dickinson was quoted as saying, “We are idiots.” And so the old microbudget filmmaking adage goes, “It’s better to ask forgiveness than permission.”

Does the festival not understand how toxic its continued association with the free-speech stiflers at Brookfield really is? Perhaps it’s too easy to assume that film festivals are liberal institutions (John Milius is planning to start one any second I’m sure), or that the rank-and-file festival goers, happily attending an event co-sponsored by such an institution, will feel complicit in the shunting of our political discourse and the massive, police-sponsored censorship and brutality that went down on their quasi-public property. Of course, for a festival started ostensibly in the shadow of 9/11 not to deal in any way (not even a panel!?) with the largest news/socio-political event to happen in lower Manhattan since the financial crisis of 2008 is in and of itself telling; indeed, one was able to go to the Tribeca Film Festival this year without ever knowing that Occupy Wall Street existed. (It’s been five years since Trinity Church, right down the street from Zuccotti Park, was a screening venue). Shouldn’t we demand of film festivals that they don’t shy away from the local troubles, that they take a stand in the face of controversy, that they do their best to actually mean something, despite the healthy checkbooks of their corporate underwriters? Why do corporations get the space to fancy themselves into whatever civically-minded mold they want to pretend to fit into on Mr. De Niro’s screens, in front of our impressionable eyes, but the people on the streets get ignored or caricatured yet again?

Of course, the rich are easily caricatured too. If you caught the movies set in the fashionable precincts of New York at the festival this year, you got no hint of discord, of the society in strife that we inhabit. That seems to be the case even if your movie is about a young intellectual, such as Greta Gerwig in Daryl Wein’s mostly assinine, Fox Searchlight-bankrolled Lola Versus. Of course, guessing from her character’s fly NYC digs and country-home getaway, from the fact that this apparently ambitious academic woman on the verge of giving a dissertation can only talk in overwritten yet still clumsily modern dialogue about some cookie-cutter arty hunk who dumped her at the end of the credit sequence like so many mumblebores of yesteryear, one guesses her career in academia isn’t so pressing. I certainly doubt she has any student loans. Bill Pullman took care of all that. I also doubt Ms. Gerwig was as insipid as her character here in her own Barnard days; surely someone as intelligent and driven as her deserves to play a smart person every once in a while? At least co-writer/co-star/director’s muse Zoe Lister Jones gives herself some ace lines and the movie comes right out and admits, in its hamfisted way, to the black tokenism that would have gotten Girls out of the whole representational hot bath concerning its lack of color.

Of course, the rich are easily caricatured too. If you caught the movies set in the fashionable precincts of New York at the festival this year, you got no hint of discord, of the society in strife that we inhabit. That seems to be the case even if your movie is about a young intellectual, such as Greta Gerwig in Daryl Wein’s mostly assinine, Fox Searchlight-bankrolled Lola Versus. Of course, guessing from her character’s fly NYC digs and country-home getaway, from the fact that this apparently ambitious academic woman on the verge of giving a dissertation can only talk in overwritten yet still clumsily modern dialogue about some cookie-cutter arty hunk who dumped her at the end of the credit sequence like so many mumblebores of yesteryear, one guesses her career in academia isn’t so pressing. I certainly doubt she has any student loans. Bill Pullman took care of all that. I also doubt Ms. Gerwig was as insipid as her character here in her own Barnard days; surely someone as intelligent and driven as her deserves to play a smart person every once in a while? At least co-writer/co-star/director’s muse Zoe Lister Jones gives herself some ace lines and the movie comes right out and admits, in its hamfisted way, to the black tokenism that would have gotten Girls out of the whole representational hot bath concerning its lack of color.

Even if the problems here at home went unnoticed or uncared for, there was plenty of international trouble to absorb on screen this year. It is now customary for Tribeca’s award winners to be announced on Thursday, so the last weekend offers press and festival goers a better chance to catch the winners and some of what they missed. Despite the lopsided number of American entries in both the world dramatic and documentary competitions, the top prizes went mainly toward films set in far-flung places, such as Kim Nguyen’s African child-soldier drama War Witch, which won the jury prize in the narrative feature competition and the prize for best actress for its star Rachel Mwanza. Unseen by this critic, it was of a piece with many of the other jury winners, which took us to Cuba (best actor, cinematography and new director winner Una Noche), Argentina (best screenplay winner All In) and the coasts of Kenya (best new documentary director went to Jeroen Van Velzen for his sumptuous Kenyan shaman documentary Wavumba, one of the fest’s true finds).

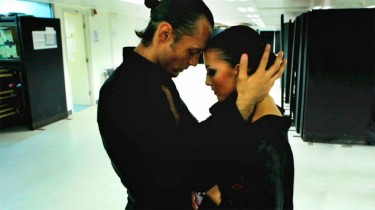

So it’s all good. I finally caught up with a pair of terrific films I missed at other fests, one you’ll hear much more about (Julie Delpy’s utterly charming, Obama-era tinged 2 Days in New York, which Magnolia will drop this summer and is as potent a reminder as ever that Jungle Fever is 20 years old) and one you might not (Sharon Bar-Ziv’s riveting Israeli military chamber drama Room 514). And along the margins of the program, one could find a doc like Andreas Koefoed and Christian Bonke’s Ballroom Dancer (pictured here), about ex-World Latin Dance champion Slavik Kryklyvyy’s attempted comeback after a breakup with his girlfriend/partner and a slow slide into irrelevance throughout the aughts. Framed, shot and cut like a narrative, it is made with a level of access that allows the filmmakers to glimpse the emotional complexity of Slavik’s exploits in a way that feels at once manufactured and yet more immediate than docs employing more traditional aesthetic strategies. It was good enough to transport me for a second, away from memory of that crass series of logos that opened the program, and for that I am thankful.

So it’s all good. I finally caught up with a pair of terrific films I missed at other fests, one you’ll hear much more about (Julie Delpy’s utterly charming, Obama-era tinged 2 Days in New York, which Magnolia will drop this summer and is as potent a reminder as ever that Jungle Fever is 20 years old) and one you might not (Sharon Bar-Ziv’s riveting Israeli military chamber drama Room 514). And along the margins of the program, one could find a doc like Andreas Koefoed and Christian Bonke’s Ballroom Dancer (pictured here), about ex-World Latin Dance champion Slavik Kryklyvyy’s attempted comeback after a breakup with his girlfriend/partner and a slow slide into irrelevance throughout the aughts. Framed, shot and cut like a narrative, it is made with a level of access that allows the filmmakers to glimpse the emotional complexity of Slavik’s exploits in a way that feels at once manufactured and yet more immediate than docs employing more traditional aesthetic strategies. It was good enough to transport me for a second, away from memory of that crass series of logos that opened the program, and for that I am thankful.