Back to selection

Back to selection

AFI Fest 2012: Antiviral and Caesar Must Die

Brandon Cronenberg's Antiviral

Brandon Cronenberg's Antiviral In diagnosing a cultural affliction without so much as mentioning a possible cure or even treatment, Brandon Cronenberg’s Antiviral coldly suggests that it’ll only continue to spread. The outlandish-but-believable premise – involving a high-end clinic that harvests and sells celebrities’ infections to their obsessed fans – brings to mind both Children of Men and, of all things, Idiocracy for how depressingly realistic its vision of the near future ends up being. We want to think that something like this could never happen, but there’s more than a little evidence to the contrary. The fact that nearly every element of the film exists solely to either comment on or expand its central point at times makes it feel a bit one-note, which is to say that what’s onscreen is engaging more often than not but also leaves little to the imagination both visually and thematically. It’s also damaged somewhat by the fact that it wasn’t shot on film: there’s a nice balance here between the gritty and the antiseptic, and the digital look has a tendency to upset the balance in favor of the latter. For as easy as it would be to dismiss Cronenberg’s debut as a low-rent imitation of his father’s early body-horror innovations, however, it would also be only partially true: Antiviral may be a somewhat minor work, but it’s also a promising one.

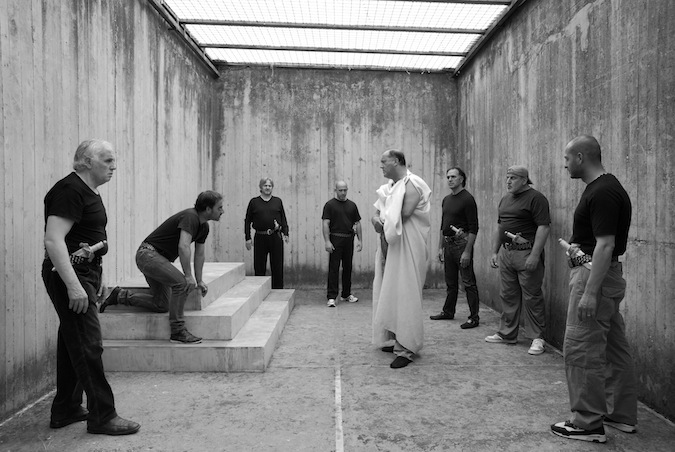

Paolo and Vittorio Taviani’s Caesar Must Die, meanwhile, is the very definition of a grower: the kind of film whose seeming straightforwardness is a guise for how slyly inventive it is. Shot on black-and-white in Rome’s maximum security Rebibbia prison, it tells the story of a small band of prisoners (many of them actual lifers) putting on a production of Julius Caesar. What little we learn of the men – their names, ages, and crimes – comes via superimposed text as they give their individual auditions to the prison officer directing the play.

Most interesting here is the way the play’s characters’ inner lives reflects a clash with the caged men portraying them. In appearing to use it merely as a framing device, the Tavianis have in certain regards made their film an austerely roundabout adaptation of Shakespeare’s play: nearly every scene consists of the men hosting informal rehearsals around the prison on their own time, so much so that we’re not always sure whether they’re reciting lines or carrying on normal conversations. Which isn’t quite to say that the actors gradually come to portray their characters throughout—that would both overstate the gimmick and undersell the dynamism. But there is enough genuine push-pull (not to mention humor) to keep us guessing.

Whether it’s the masterpiece its Golden Bear at Berlin earlier this year implies still feels difficult to gauge, but suffice to say that Caesar Must Die is something special, something else. Hindsight feels especially kind to this one, and as it rests in the mind its more subtle machinations fall into place in a most satisfying way. And for all it has to say about our relationship to art, nothing it offers ends up being more resonant than the simple idea – made clear in the first several minutes – that the characters’ reprieve is just that: a transportive but fleeting interlude. The men all remain prisoners at film’s end, just as several of the incarcerated actors do today. Escapism is wonderful, but freedom is better.

Follow Michael on Twitter: @slowbeard