Back to selection

Back to selection

First Winter Opens at Videology

Michael Tully of Hammer to Nail passed along this review of Benjamin Dickinson’s First Winter, written by fellow filmmaker Zach Clark. First Winter is an accomplished, compelling and unexpectedly timely first feature, but I debated a second about posting this. That’s because Clark is also the programmer of Videology, where the film is premiering tomorrow. That said, he opens with a quote from Andrei Tarkovsky so, with this disclaimer, I was cool to run it. — SM

First Winter, Benjamin Dickinson’s microbudget entry into the slow-burn apocalypse pantheon, owes no small debt to that scant subgenre’s zenith – Andrei Tarkovsky’s The Sacrifice. It seems entirely appropriate then, that a quote from the mustachioed master best sums it up. Here it is:

“’Man is born unto the trouble as the sparks fly upwards.’ In other words suffering is germane to our existence; indeed, how without it, should we be able to ‘fly upwards?’”

A group of twenty-to-thirtysomething yoga devotees find themselves stranded in a house in upstate New York with their power down, an ominous and enormous cloud of smoke looming in the distance and their food supply rapidly dwindling. Through sex, drugs and meditation, they try to forget their dour situation. But when disease, death and hunger creep their way in, they must face the facts and each other in the process. They must suffer, and whether or not (and to what degree) they’re able to “fly upwards” becomes the narrative’s driving force.

With parts of New York still powerless and a recent Nor’easter blanketing us with snow, the film’s scenario isn’t unimaginable by any stretch. Even with recent events aside, there’s an intimate, microindie authenticity that smartly plays against the high concept genre elements. Almost all the actors use their own names. For every special effect, there are at least twice as many events that are not faked, from chopping down trees to hunting animals for sustenance. A small film crew holed up in a house isn’t that different from a walled-off spiritual commune.

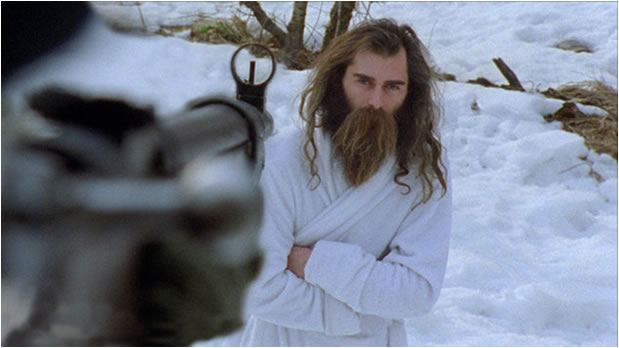

Delicately lensed on 16mm, the palette moves between the cold, washed out expanses of a winter day and the warm, cozy hues of rooms lit by firelight. Bold spikes of bright red make memorable appearances in the forms of a wool cap, a pair of boots and thin melting candles. Dickinson alternates between a vérité handheld camera that allows us to discover spaces as the characters move through them, and simple, deliberate formalism. When one technique interrupts another, it’s significant. In a film so light on dialog, the aesthetics become the most vocal member of the conversation.

In addition to its premise and palette, First Winter shares The Sacrifice’s interest in time. The apocalypse will bring many trials and hardships, but it will also bring a lot of time to kill, which is a trial and hardship in and of itself. As things get tougher, the silences get longer. The visceral effect of the long take is especially potent during a sequence of the group silently consuming what little scraps of rice are left for them. In asking patience from his audience, Dickinson also invites them to actively engage with his characters and become a member of the group. This pays off in the end, as the film’s longest take is also its most transcendent.

Aesthetically assured and emotionally true, First Winter is ambitious by means of its limited resources, rather than in spite of them. Those willing to “suffer” along with it will be surprised how much they’ll find themselves flying upwards.