Back to selection

Back to selection

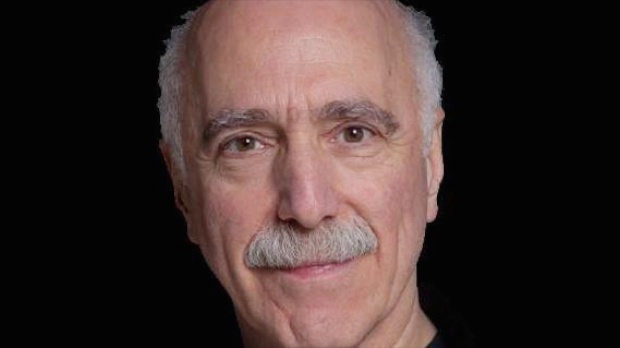

Remembering Richard Brick

Cancer is taking a toll on our postwar generation of filmmaker activists, and now we mourn Richard Brick.

Richard was a coiled spring whose febrile energy made him a one-man power station, radiating waves that enveloped you and insisted that you pay attention. Whether he was running the Mayor’s Office of Film & Television, chairing the Board of Directors of the IFP, helping to run Columbia University’s graduate film school, teaching his famous pre-production class, or trying to bring a director into line (most famously Emir Kusturica), his verve, passion and discipline were a wonder to behold.

The various obituaries stress Richard’s role as New York City’s first film commissioner, a mandate to which he brought clarity of vision and a line producer’s no-nonsense know-how. But I want to stress his identity as indie film producer par excellence. Like his mentor Mike Hausman, Richard was dedicated to supporting the writer/director’s conception, no matter how challenging.In fact, it was the challenge he relished.

One of the fledgling directors he championed was Bronx-born Joe Vasquez. The film they made together, Hangin’ with the Home Boys, is still one of the lights of the indie film movement. Few of our colleagues were as proudly, defiantly, recklessly set on independence as Richard. So, it is no surprise that he dedicated himself to the IFP and served as its Chair for a number of years.

Richard had so much excess energy that, as Nancy Sher reminded me, during meetings of the IFP Board he would loudly tear the papers in front of him into neat strips, a habit his colleagues found horribly annoying or hilariously endearing (or both).

Few people were more blunt than Richard Brick. Writing from France, IFP’s former Executive Director, Catherine Tait, recalled, “Richard used to brusquely fire instructions at me, ‘Do this or do that, Catherine!’ And then after barking at me, he would laugh and say, ‘Do whatever you think is best.’…I loved him for this!”

He was even more single-minded when imparting his philosophy of film production to his Columbia students. Nancy, who took his course, remembers his saying, “There are many ways to board (meaning, schedule) a picture, but there is only one right way,” (meaning, his). Richard loved to share his knowledge and he loved to help you. Just this week, I’ve had three reasons to call him for advice and sadly hung up the phone.

Richard’s brusqueness was always tempered by his warmth, his sly wit and his marvelous laughing eyes. His heat was palpable, and he flaunted it. He could be an outrageous and flattering flirt, yet if you knew him, you knew he was uncompromisingly devoted to the two extraordinary women of his life: his first wife, the filmmaker Geri Ashur, who died at the tragically young age of 37, the mother of Richard’s son Noah, and his second wife, Sara Bershtel, the distinguished intellectual, publisher, and co-author of Saving Remnants (a book that exerted a great influence on my thinking), who survives him.

During the years between Geri’s death and his marriage to Sara, Richard was a fiercely protective and doting single father to Noah. His determination to be a good, wise and loving parent is one of the qualities that always touched me so deeply.

It’s impossible to sum up a man as dynamic and charming as Richard Brick. It’s like tying to stab someone in the dark. One flails.

I prefer to let him continue to evolve in my heart and memory, a man for all seasons, a man for all time, a fiery defender of what he believed to the end.

With love…