Back to selection

Back to selection

Anything Can Happen: True/False’s Sidebar Neither/Nor 2015 Investigated Polish Documentary Traditions

How to Live

How to Live Now in its third year, the Neither/Nor sidebar of the annual True/False Film Festival has quickly become both a fundamental facet and essential rejoinder to the curatorial ideal of the program proper. Free of categorical imperatives, the festival’s binary brand has become over time a kind of shorthand for an often uncategorizable strain of filmmaking in which the ethos of nonfiction is consistently complicated by the visual language of fiction. The idea behind Neither/Nor is the reconstruction of a continuum between past and present iterations of this method, teasing out parallels between classic and contemporary storytelling modes while contextualizing the social and political particulars of bygone movements through their given cultural and cinematic milieus.

Following programs dedicated to the ‘60s New York underground and the Iranian New Wave of the ‘90s, this year’s slate cast the widest net yet, focusing on the “chimeric cinema” of Poland from the ‘70s-‘90s. Curated by critic Ela Bittencourt, the series featured 15 films from six different directors, covering as large a stylistic spectrum as it did a historic span. Films were just as often paired by thematic essence as they were by directorial credit; even when viewed from the earliest selection (1972) to the most recent (1998), little visible evidence is offered as to the individual films’ date of production, so cohesive is their collective conception. Much of this continuity can likely be attributed to the communist climate these filmmakers were forced to weather over this period, but there’s a compassion and spirit of humane resolve coursing through even the most formally disparate of these films.

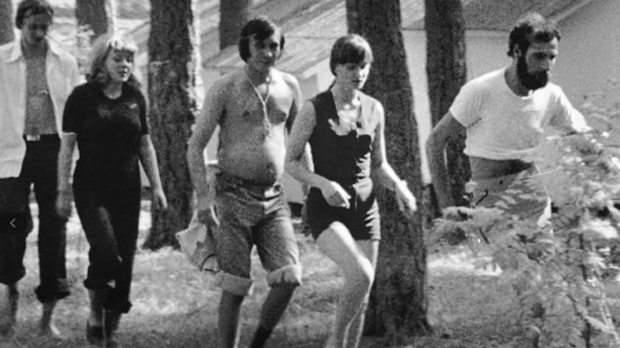

With five films, Marcel Łoziński was the most represented filmmaker in the program, and in many ways he’s representative of the artistic and aesthetic scope of his compatriots. Łoziński’s 1981 feature How to Live is exemplary of his early approach to nonfiction storytelling, including introduction of external elements for dramatic incitement. Set at a remote, government-sanctioned commune, the film depicts the day-to-day activities of a group of families lost to the influence of socialism — except that two inconspicuous couples have been brought along and integrated, with assigned sympathies and motivations, by the director himself. What transpires seems at first fairly typical of such a set up, as campers interact, exercise, and enjoy group activities. But when a competition is enacted by the camp administration to anoint a model socialist family, personalities are pitted against each other as tensions arise between participants. The circumstances left Łoziński, his crew, and most especially his “actors” in a vulnerable state, with the spontaneity of the resulting drama forcing the director at one point to restage a physical altercation which had transpired between one of his friends and a frustrated camper.

Łoziński utilizes similar methods in many of his films, in an effort to — as he calls it — “thicken reality.” In both the 1993 short 89mm from Europe and 1995’s medium-length Anything Can Happen, he inserts his son Tomasz into the equation. The former finds the then-four-year-old child disembarking from a train and striking up a conversation with the rail workers who’ve we previously watched tend to the maintenance of the tracks. In the latter, the young Łoziński is sent to a park in Warsaw to converse with a diverse selection of elderly strangers. Precocious with offhand insight, Tomasz engages these men and women in discussions of aging, history, and relationships, striking an emotional chord in the heart of these seniors through an at once humorous and heart stirring mix of candor (“Are you alone and unhappy?”) and conciliation. This fusion of factors — this attempt at “moving towards a situation that already exists, or has a potential to exist” — lends Łoziński’s work a subtle structural volatility. Despite the tranquility of each film’s provincial setting, anything truly can happen.

The disruption of idyllic environs is a key thematic virtue in the films of Bogdan Dziworski — by any measure a major discovery and a talent emblematic of Neither/Nor’s expanding stateside significance after a pair of recent international retrospectives first brought the director’s name back into the critical conversation. A professionally trained photographer who worked as a cinematographer and multimedia artist before directing only about a dozen documentary shorts, Dziworski’s filmic work is wholly indicative of his background in the visual arts. His films are something like physically reanimated portraiture, hypnotizing records of bodies, motion and performance. Two standout selections epitomize his formal approach: Both 1978’s Biathlon and 1983’s A Few Stories About a Man capture the human body in a number of fight-or-flight scenarios, as various anonymous figures attempt to engage both their anatomical capacity and the inertia of their natural surroundings. Biathlon consists primarily of decelerated footage of downhill skiers as they fly skyward from the slopes and float mid-air before crashing to the snow beneath — one shot after another of skiers taking off, hanging perilously above a sea of spectators, breathless visuals which Dziworski and his editor Agnieszka Bojanowska cut into a montage of precisely patterned movement broken only by the inevitable parade of unfriendly landings.

A Few Stories About a Man, meanwhile, takes the human vessel as its central subject. The man of the film’s title (an unidentified Jerzy Orłowski) has no arms, but does, as we quickly find, have an impressive physical drive belying his handicap. The film, like Biathlon, is made up of a series of short, vignette-like scenes in which the body is pushed to its corporeal limits. Orłowski is seen jumping, diving, and skiing in a variety of potentially hazardous settings – from deserts to rivers to mountains – while privileged moments between him and his son hint at the full life he’s chosen to live without the benefit of ordinary conveniences. Dziworski’s images are correspondingly resourceful, sitting mostly fixed at odd angles, allowing Orłowski to drift through or intrude upon the frame. However, it’s the director’s expert use of sound that proves most intriguing. Isolating, synchronizing, and in many cases divorcing noise and effects from individual onscreen actions, Dziworski creates a three-dimensional sound world of splashes and crashes, effort and exertion, heightened yet frighteningly immediate to the senses. This careful negotiation of the audio/visual divide is a defining characteristic of Dziworski’s work, whether documenting athletics, as in these two films, or something less obviously thrilling but equally practiced, like the behind-the-scenes operations of 1979’s Arena of Life and 1984’s Szapito, complementary films concerning troupes of circus performers at different stages of their professional lives.

Speaking about his work, Dziworski is both cagey and forthright. “Film is one big wonderful lie,” he’d say during a post-screening Q&A, after announcing his intention of making a film about a six-month-old local in the style of Andy Warhol. Not the most apparent influence upon Dziworski or, really, any of these filmmakers, Warhol was still a talking point for many of Neither/Nor’s featured guests. Dorota Wardęszkiewicz, editor of the 1991 short documentary Hear My Cry, referenced Warhol’s Sleep and the director’s ideological aversion to extraneous editing as an integral facet of her own approach. Hear My Cry, a powerful and historically vital film by director Maceij Drygas, is built around such editorial discretion. Following the fall of the Polish People’s Republic in 1989, Drygas went about researching a shocking, almost entirely undocumented event in his country’s political past. In 1968, a man named Ryszard Siwiec set himself on fire at the annual Warsaw Harvest Festival in protest of increasing socialist stratification. With only seven surviving seconds of footage of his self-immolation at their disposal, Drygas and Wardęszkiewicz construct a living history of Siwiec’s plight and passion, interviewing his surviving family, recreating moments of research and discovery, and, most importantly, prudently unveiling the actual sight of the harrowing incident. Reminiscent of the work of Claude Lanzmann, Hear My Cry functions similarly as a reconciliation of historical trauma in which the act of bearing witness works to reanimate a moment of social atrocity otherwise lost to time.

While the integration of fictional properties into nonfiction frameworks was the general principle behind a majority of the series’ films, one artist took the opposite approach: Grzegorz Królikiewicz, a film theorist and professor, whose first film from 1972, Through and Through, accounts for both the earliest Neither/Nor title and perhaps its most progressive. Nominally a fiction filmmaker, Królikiewicz would nonetheless frequently take real people as his subjects, mounting expressionist docudramas by enlisting non-actors and restaging biographical events, often in the very location of their origin. To tell the tale of partially crippled Polish chess champion Bronek Pekosiński in his 1993 film The Case of Pekosiński, for example, the director brought in the eponymous character (now in his fifties) to play himself at every age of his fictionalized life. While his methods for Through and Through, based on the trial of a young Polish couple who were driven to murder as a means for survival, weren’t quite as elaborate as his later film, Królikiewicz managed to meld fact and fiction in an equally unique manner. Charting the initial throes of the relationship with a vérité sense of realism, the film slowly breaks free from the constraints of verisimilitude, assuming a hallucinatory sense of progression as the doomed romantics eventually find themselves before a judge in the exact courtroom where their counterparts’ sentences were first handed down. A literal translation of Through and Through’s title is Inside Out, and the complexities embodied by that seemingly contradictory expression is appropriately symbolic of not only these 15 wide-ranging films, but of a program and a festival built on such broadly refreshing considerations of genre.