Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

Behind The Graduate‘s “Leg Shot”: Daniel Raim on Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story

Two unsung heroes of the American film industry get their due in Daniel Raim’s extraordinary documentary Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story. Most filmgoers – even the most informed ones – have probably never heard of Harold and Lillian Michelson, but the history of movies was forever changed by their contributions to classics like The Ten Commandments, The Graduate, The Apartment, West Side Story, and DePalma’s Scarface. Harold was a storyboard artist and Lillian ran a massive Hollywood research library; separately or together, they were essential resources for directors including Alfred Hitchcock, Francis Coppola, Danny DeVito, and Stanley Kubrick. They also, as Raim’s film shows, were deeply in love, and Raim expertly balances reportage of their artistic accomplishments with a powerfully moving and richly complex portrait of a marriage. In keeping with the modesty of his subjects, Raim’s approach is straightforward and unassuming, but the simplicity is deceptive – it takes a lot of filmmaking skill to create something as pure and profound as Raim has here, and to operate on so many levels so effectively. Glenn Kenny summed the film up perfectly in Vanity Fair when he called it “a wonderful paradox: an educational tearjerker.” Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story taught me more that I didn’t know about the movies I love than any other documentary I’ve ever seen; that it also taught me more about the challenges and rewards of sustaining a marriage than any film before it, fiction or non-fiction, is some kind of small miracle. I spoke with Raim a couple of weeks before the movie’s New York premiere; it will open on April 28 at the Quad in conjunction with a retrospective of Harold and Lillian’s work.

Filmmaker: How did you first become aware of Harold and Lillian Michelson?

Daniel Raim: I first met Harold and Lillian in 1998 when I was a student at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles. My prior training was in documentary filmmaking, but I could not turn down the opportunity to study under one of Hitchcock’s most esteemed collaborators, production designer Robert F. Boyle (North by Northwest, Marnie, The Birds). One day, Bob invited Harold Michelson to teach a class on storyboarding. Their collaboration began on The Birds, and Harold taught us his camera angle projection technique, which means drawing a storyboard that can show us exactly what the camera sees, given a specific lens of the camera. This is all pre-digital, and Harold’s innate sense of cinema was incredible. The way he could bring a scene to life both verbally, and on paper. But Harold’s class almost put me to sleep because all these pre-digital techniques he was teaching us at AFI had more to do with geometry than with filmmaking.

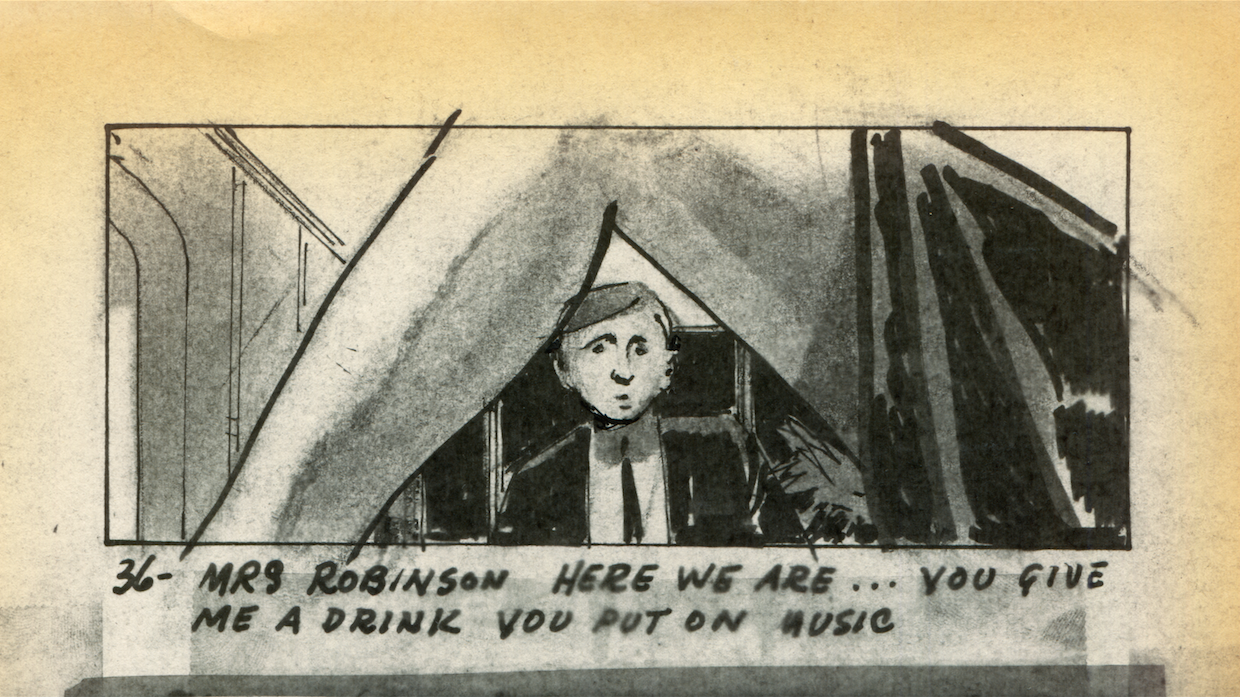

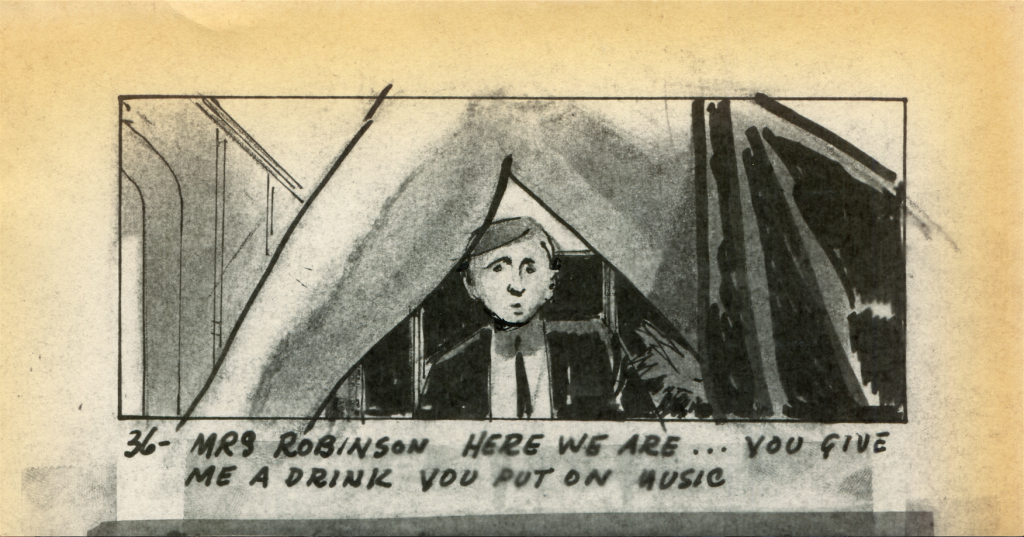

Two years later, when I was making my first documentary The Man on Lincoln’s Nose (2000), I had the opportunity to film Harold walking us through his creative process. He took an elevation plan of Mrs. Robinson’s house from The Graduate and laid his camera angle on it. He could then open The Graduate screenplay and start dreaming up these shots that brought the action and words to life. I was eager to make this new film partly because I wanted to highlight Harold’s contributions and his working methods, which were fascinating to me. And beyond Harold’s storyboarding techniques, I wanted to shine a light on his extraordinary “cinema mind” and his ability to conceive shots and sequences that are now considered some of the most iconic in American film history. Neither Harold or Lillian wanted or cared for the spotlight. I hope this film will change our understanding of what they did, technically, and also their unique, unheralded contribution to the movies.

Filmmaker: So how long after meeting Harold did you take the first steps toward making a documentary about him and Lillian?

Raim: I started making this documentary in earnest around June 2013. But long before I ever considered making a film about Harold and Lillian’s inspiring love story (a romantic partnership that lasted nearly 60 years), I aspired to make a short film on Lillian and her research library and another short film on Harold. In 1999, I had filmed two career-spanning interviews with Harold and they were just sitting there in my hard drive, calling me to do something with them.

I started filming in June 2013 with the intention of making two short subject documentaries: one about Harold and one about Lillian. After filming a few interviews with their close friends and colleagues, it became clear that Harold’s story can’t be told without Lillian, and her story can’t be told without him. I was also filming a profoundly moving love story, chronicling how these two people overcame very difficult times to maintain their marriage, highlighting what was ultimately a profoundly moving and challenging romantic and creative partnership. The challenge was visualizing a story that took place in the past. Reenactments were not the right fit for this film — it’s a movie about two visual artists, so naturally we needed to find a way to tell their story through drawings.

Beyond the technical approach, there was the challenge of discovering themes and a strong narrative within their love story that would resonate with me and with the audience. How do I get beyond all the warm and fuzzy feelings? How do I get Lillian to truly open up and share aspects of her and Harold’s lives together that were potentially unflattering? Albert Maysles talked about the importance of having empathy for your characters while filming, and that was a vital lesson for me. That non-fiction filmmaking is also about listening.

It was a leap of faith for me to decide to make a feature film that investigated both their romantic and creative lives together, and how both of those aspects fed into each other. They worked on each other’s movies. Lillian fed ideas and research and images to Harold that he would then use in his storyboarding. Lillian is a secret storyteller. The best artists working behind the scenes were secret storytellers and Harold and Lillian were considered by the best directors, producers, and production designers as “Hollywood’s secret weapon.” But it’s not like they worked in the same office, or even the same studio all the time. Some of their best work was done at the dinner table.

I lived this firsthand because my wife Jennifer Raim, who is a very talented editor, was also the co-editor of Harold and Lillian. Some of her best ideas would come while life was happening at the same time. I really appreciate that and wouldn’t have it any other way.

Filmmaker: How did you approach Harold and Lillian with the idea, and what was their initial response?

Raim: Sadly, Harold passed away in 2007. When I asked Lillian’s permission to make a documentary about Harold in 2013, she was delighted. Then that idea evolved in making two short films, one about Harold and one about Lillian. So Harold and Lillian was never conceived out of the gate as a feature-length documentary love story about their lives and careers. It really evolved over time as I slowly discovered the story and found a way to tell it that excited me and piqued my curiosity.

It really is a process of discovery, and having a certain openness to going down roads you didn’t anticipate from the get go. I saw Agnes Varda introduce her profoundly moving and intimate personal doc The Beaches of Agnes, and she offered the audience some truly wonderful advice about documentary filmmaking. She spoke about the importance of taking chances and that “there has to be some risk involved when making a film.” And with Beaches, Agnes told us that the risk for her was making a feature film from all these loose ends, all this disparate life material that spans her entire life and marriage with Jacques Demy, and turning that into a movie. I could truly appreciate that and have carried it with me into the projects I work on. Some of my favorite works of cinema, fiction and nonfiction have a collage-like structure, and for me the risk was telling a story that explores the tension between Harold and Lillian’s personal and professional life, finding meaning from that through the editing process.

Filmmaker: How did you get them to open up on camera?

Raim: Both Lillian and Harold are camera shy. I don’t think I’ve ever met two people that are more camera shy. I think that speaks to the fact that they have no ego about their accomplishments. And Lillian was unwilling under any circumstances to talk about anything private during our initial interview in 2013.

Our first interview involved a traditional camera crew and set up, with three-point lighting and make up, and she wanted to know all the questions in advance. I took the bait. I was just so pleased to even get her to agree to an interview. But it turned out to be a disaster for me on a creative level. Sure, I got some great anecdotes, but that’s not going to cut it for a “spiritual” documentary about her life with Harold. I needed to rethink the entire plan. So I called Lillian and told her that I wanted to come by her home (at the Motion Picture Television Fund home) and just talk about life. It would just be the two of us, and I casually mentioned that I would be bringing a small video camera with me. She agreed. When I arrived to her room it was very casual, we were just chatting as always, and I set up my camera – a small Lumix GH3 – on a tripod about eye level, opened the curtain for some natural light, and we began to chat. As always. Then I casually asked her to clip on a small lav and told her I had some questions I wanted to ask her. She pointed to the camera and with a grin asked me, “You’re not going to be recording this, are you?” I assured her with a wink, “No of course not. I just want to talk with you about life, and if anything interesting comes out from our conversation, I might consider including it in the documentary.” “Ok,” Lillian replied with a smile. This seemed to do the trick, so I fired up my camera and we chatted for about 90 minutes. And Lillian forgot about the camera and it was a conversation, not an interview.

After this, I interviewed Lillian on camera about ten times over the course of an 18-month period. That’s how I made the film. With each on camera interview our conversations became deeper and more involved as she was sharing with me certain life experiences that any human being could identify with. This doc was slowly transcending a traditional behind-the-scenes doc about an unsung Hollywood power couple. Lillian bared her soul in a tender, witty, philosophical and deeply moving way. At times, I could feel Harold’s presence in the room.

Filmmaker: Talk a little about the selection process, because obviously the Michelsons worked on so many great films that to cover everything would take many, many hours. How did you choose which movies and which phases of their careers would get special attentive and be representative of their whole bodies of work?

Raim: I think that’s a great question becomes it reminds me of the painful experience of having to cut scenes that I loved — scenes that inspired me to make the film in the first place. I’m a big Star Trek: The Motion Picture fan. The film was directed by Robert Wise in 1979, and Harold was the production designer on that picture. We were fortunate that David C. Fein, who executive produced the director’s edition, interviewed Harold in-depth about designing the first Star Trek movie. And we cut a great sequence about Harold’s contributions on that film. He did things that have carried on to this day inspiring the look of successive Star Trek films and TV series, and he was Oscar-nominated for that film. But this was the third act of Harold’s life, and also the third act of our documentary. And no matter how fascinating the story is, a film has its own internal clock, and I needed to respect that and cut the sequence. Not altogether, I left some of it in. Now Trekkies can enjoy that sequence as a DVD bonus! That’s an example of what I had to cut, but it was clear to me from the beginning that I needed to showcase some of Harold’s key contributions to cinema as a storyboard artist on The Ten Commandments, The Birds, and The Graduate.

There were other beloved scenes that didn’t make the cut, such as Harold’s insight into his favorite movies, Citizen Kane and Amarcord, and his visual contributions to Irma La Douce and The Apartment, West Side Story, Johnny Got His Gun, The Fly, History of the World: Part I, and some other great films.

For Lillian, it was essential to weave into the narrative some of the highlights of her career, such as Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf”, Rosemary’s Baby, Full Metal Jacket, Fiddler on the Roof, The Birds and Scarface. Lillian worked on hundreds of classic American movies and offered great stories that will see the light of day in the Blu-ray bonus section, including her work on Chinatown, The Exorcist, The Hunt for Red October, War Games, and more.

Filmmaker: Was the structure of the film something you had in mind from the beginning, or did it evolve as you conducted interviews not only with the Michelsons but all of the other people who had worked with and been influenced by them? Was it difficult finding a balance between the love story and the film history material?

Raim: The structure evolved over the course of two years, as my conversations with Lillian grew more and more complex and personal. Her inner story is the driving force of the film, and I wanted Lillian’s story first to inform the structure, then their personal story, and finally their careers. The other aspect of creating the structure was the challenge of telling a story that spans 60 plus years in 94 minutes. Some screenwriters recommend avoiding the “cradle to the grave structure,” because it’s too broad and encompasses too much. Normally, I would agree with that, but the story I wanted to tell was about lives lived and the critical and often very difficult life choices we make that play a big role in our life journey. These choices often feel as though we are going against the grain of what the world around us expects and wants us to do, and following our own instincts and desires. And for Harold and Lillian, that story of going against the grain is set in the past. My goal was to somehow dramatize their real-life events and set them in the present, so that the audience could go on that very intimate journey with Harold and Lillian.

Filmmaker: When and why did the idea for the storyboard-esque illustrations come in, and who did them?

Raim: The storyboard-esque illustrations you see throughout the movie are the work of a very talented animator and character designer, Patrick Mate. We created these illustrations as a vehicle to bring the audience into the present tense of Harold and Lillian’s life journey together, and also use these drawings, as well as the original score by Dave Lebolt, one of the best composers I ever had the pleasure to work with.

Patrick Mate was the lead animator and character designer at DreamWorks Animation Studios when I met him. He was very fond of Harold and Lillian, and when he offered to lend his talent and genius to the film, I was over the moon. Patrick brought the film to another level with his witty, loving, and quirky drawings that underscore Lillian and Harold’s witty and loving worldview. And I think that is part of their magic, how they overcame so many of life’s obstacles with wit, love, and grace.

Patrick and I arrived at the concept of using original storyboards to tell the story of Harold and Lillian because it was organic to Harold’s life work. It also becomes a device that fuses two aspects of their lives together, the romantic and the creative, having a family and having a life.

Filmmaker: How did your perception of Harold and Lillian and their place in film history evolve over the course of production and editing?

Raim: I was unnerved by the idea of coming out with a film that says to the film world, “Hey guess what! You know that awesome shot from The Graduate we all know and love? Well, that wasn’t Mike Nichols’s idea, nor was it the cameraman’s idea. Nor was it the stars’ idea appearing in the film. That idea, and most of the mise-en-scene for The Graduate comes from this guy named Harold Michelson who wasn’t even credited in the film.” My job is to tell the story of how Harold came up with these shots with as much humility as possible.

By way of example, Harold tells the story: “Mike Nichols did rehearsing on the stage. They all sit around a table and read the script. I was there, and we had a mock-up of the bedroom, with tape, and there was a bed there. As they were talking and going through the motions with Anne Bancroft, I would be walking around to see what would be good shots for this so I can draw it up. Anne Bancroft wondered who I was and she challenged me: “What are you doing here?!” I said, “I’m doing the storyboard on this scene.” So I asked Patrick to illustrate this story and that was included in the cut I brought to the Cannes Film Festival for our world premiere.

A few months later, I needed to clear the rights to some of the stills in the movie and went to the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Margaret Herrick Library in Los Angeles to find the stills I needed. On the very last day of editing, before picture lock and delivery to our distributor, I inserted a photo I found of Mike Nichols rehearsing the exact same scene Harold described from The Graduate. And I was about to lock picture and export the film, and my wife and co-editor, Jen, points to the monitor and says to me, “Did you notice who that is?” I zoomed in about 400% and sure enough, sitting at a table in the back of the sound stage, smoking his pipe, was Harold Michelson storyboarding the scene while Mike Nichols is rehearsing with the actors. We found our smoking gun!

Filmmaker: Do you have any particular favorite images or sequences that Harold was instrumental in designing, and if so what are they and why do they stand out to you?

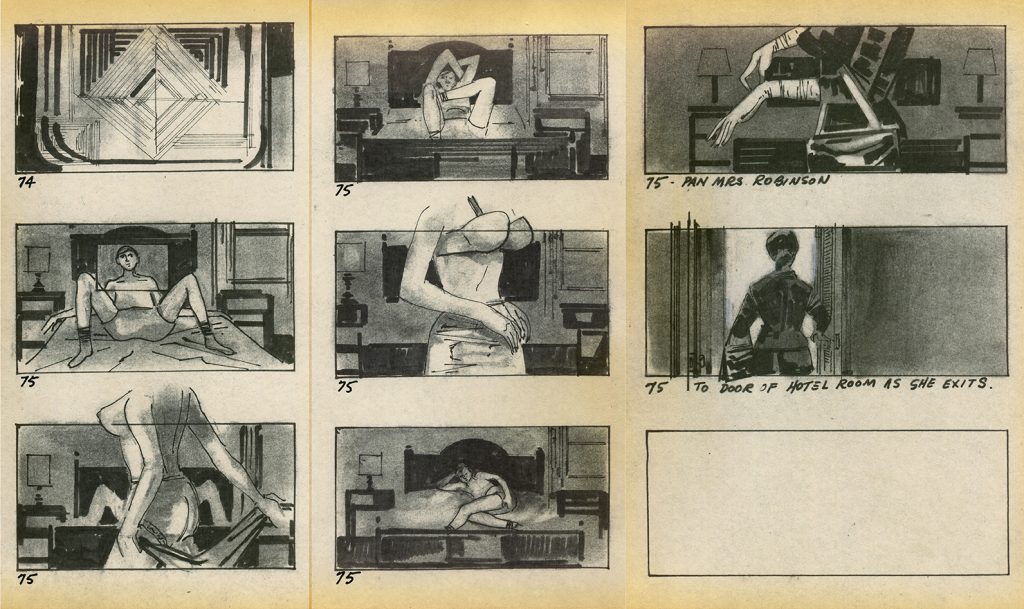

Raim: The hotel room sequence in The Graduate is one of my all time favorite sequences that Harold devised. I love hearing Harold describe how he saw it, and the storyboards depict it exactly as he describes it: “When they were in the hotel room and they were finished with their lovemaking, I took a shot from the TV set to Dustin. And I had her walking back and forth. He is watching TV. You just see him. You see her, you don’t see her head. It’s from her neck down to knees. And she walks past in front of the screen, getting dressed. She goes from left to right and she puts on her underwear. And as she goes by, she has more clothes on. Then from right to left she puts on something else. And finally the door slams. I just did it. I thought it was hell of a shot, and I’m proud of it.”

Filmmaker: I first heard about your film from Danny DeVito, who told me about it last year and spoke very highly of your work. What kind of involvement did he have beyond just being an interview subject? What did you learn from his input?

Raim: When I had an advanced rough cut of the documentary, which was about two hours long, Danny DeVito watched and called me up with some feedback: “Look, Dan, I just watched your documentary, how long is it?” I told him it’s about two hours long. Danny replies, “Well, it feels like it’s much longer then that. It feels like it’s two and half hours long. You gotta think about making it shorter.” Then Danny generously offered to run the film with him and his long-time film editor, Lynzee Klingman (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, The War of the Roses) to discuss what’s working and what’s not working. That four-hour session in Danny’s living room was a master class in film editing and cinematic storytelling, and I will never forget it. Within four weeks I submitted a cut to the Cannes Film Festival.

Filmmaker: What’s your release strategy for the movie?

Raim: We worked with Zeitgeist Films for theatrical and non-theatrical distribution. The film is going to open at the new Quad Cinema on April 28th with a combined “pocket series” retrospective of Harold and Lillian’s films. The film will open in several other cities, including May 12th in Los Angeles and May 26th in Chicago. It’s a happy coincidence that Harold and Lillian is being released two days after the 50th anniversary of The Graduate. You know, the leg shot in that movie is Harold’s concept. (Lillian claims that Harold was always a “leg man.”) I don’t want to make it more than it is. Filmmaking is an intensely collaborative medium. It’s not about who came up with which shot, and how, and when. It’s really about people working together, and I believe that Harold and Lillian felt that way too. That being said, I do think Harold should be known and recognized as one of the great film artists of the 20th century. I think we do need to set the record straight. I am really pleased to bring this story out into the world. And hopefully, we will set the record straight while also connecting audiences with Harold and Lillian’s generous and nurturing spirits.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD, iTunes, and Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.