Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

Danny DeVito on The Ratings Game, Storyboarding and Test Screenings

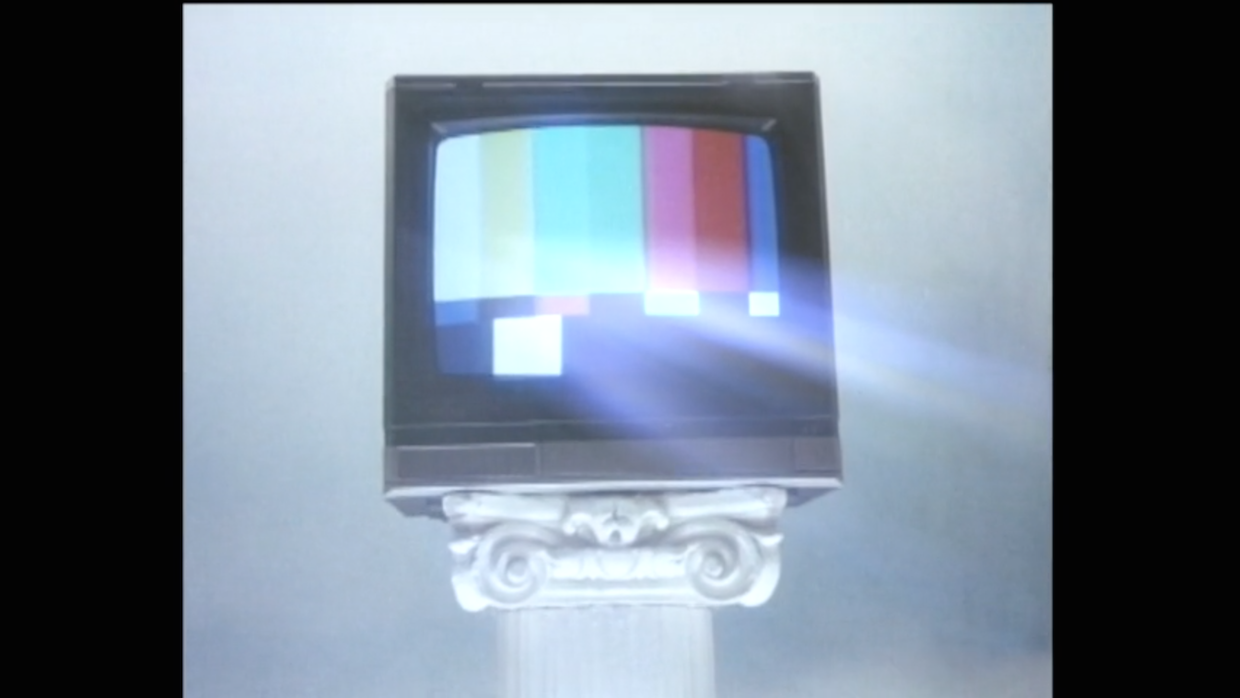

The Ratings Game

The Ratings Game In 1984, Danny DeVito made one of the most assured and entertaining directorial debuts in comedy history when he helmed The Ratings Game, a hilarious satire that premiered on Showtime only to disappear from circulation in the decades that followed. The movie tells the story of a New Jersey trucking mogul (DeVito) who moves to Los Angeles with dreams of making it in the TV business. When he falls in love with a woman (Rhea Perlman) who works for a ratings service, he figures out a way to rig the system in his favor, rising to the top with a collection of truly inane series that he has created. These TV shows within the movie are brilliantly executed by DeVito, as are the numerous other components of the film, including a touching love story, a razor-sharp dissection of the absurdities of the TV business, and an Italian-American family comedy that’s broad and authentic in equal measures. DeVito balances a multitude of comic tones and levels of reality with total mastery, exhibiting the same visual intelligence and conceptual audacity he would bring to his later masterpieces The War of the Roses and Hoffa. Sweet, biting, intelligent, and exquisitely crafted, The Ratings Game stands alongside Tootsie and Lost in America as one of the great American comedies of its era.

The Ratings Game has been difficult to find for many years, but now the good folks at Olive Films have released an indispensable Blu-ray/DVD that includes a collection of DeVito’s early shorts and some deleted scenes. It’s a busy time for the actor-producer-director, who stars on It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia and recently gave one of his finest performances as a weary film school professor in Todd Solondz’s Wiener-Dog. Behind the camera, DeVito recently completed work on a new short film, Curmudgeons, and is the executive producer of Daniel Raim’s Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story, a documentary that tells the story of Hollywood storyboard legend Harold Michelson and his wife, famed research librarian Lillian Michelson. That film will screen in Los Angeles at the American Cinematheque with Raim and Lillian Michelson in attendance on July 31 – more information on the screening can be found here.

I spoke with DeVito about all of these projects and more the week that The Ratings Game disc was released.

Filmmaker: Watching The Ratings Game again this week, I was struck by what an accomplished debut it was. How long had you been thinking about directing before that – was it something you always wanted to do?

Danny DeVito: Definitely. I started out as an actor, but somewhere around 1966 I saw Pontecorvo’s The Battle of Algiers and it got me very curious about directing. I looked at that movie and went, “What the hell? I’ve been watching movies since I was a little kid, but how did they do this?” I made some Super-8 films and 16-millimeter shorts in the late 60s and early 70s before I did One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, and then when I got the job on Taxi my acting career took off. Eventually I directed a couple of Taxi episodes and wound up working with producer David Jablin on some short films he was producing for this HBO series called Likely Stories. One of those, The Selling of Vince D’Angelo…have you ever seen that?

Filmmaker: Yeah, they put it on the Blu-ray along with some of your other shorts.

DeVito: Okay, great. David was a terrific producer, and after we collaborated on A Lovely Way to Spend an Evening and Vince D’Angelo he put The Ratings Game together. I put just about anybody that I was remotely connected to in it – not just Rhea, but a nephew of mine, cousins, and all my actor friends. We did it for Peter Chernin, who was running Showtime at the time and gave us a lot of freedom.

Filmmaker: It’s a meticulously crafted movie in terms of the compositions and camera moves and transitions. Is all that planned out pretty far in advance of shooting?

DeVito: Yes, that’s the way I’ve always done it. I started working that way because I like to act in the movies that I direct, so I planned out my shots ahead of time as a sort of security blanket. And as I watched a lot of movies and studied other directors over the years, I just got the feeling that that was the way to work for me – to know what I was going to see and have it be the result of careful planning and design. I storyboard everything, and I was really fortunate after The Ratings Game to work with Harold Michelson, who was an amazing storyboard artist. He’s passed away, and now there’s a movie about him that I’m involved with called Harold and Lillian: A Hollywood Love Story. It’s directed by a guy named Daniel Raim, and it gets into all the iconic images that Harold created – one that comes to mind right away is the shot in The Graduate of Anne Bancroft’s leg with Dustin Hoffman in the background. That was one of Harold’s incredible contributions to that film. His wife Lillian had an incredible research library that you could use in the days before the Internet if you needed to look up a certain kind of building or what people were wearing in a specific period; I met her many years ago when she was working with Coppola, and then Katzenberg wound up taking the library to Disney. It was in the days where you got hard copies of everything – literally, she’d bring a book over with everything from the period you were looking for. She and Harold were a perfect couple. I met them both at the same time, along with a guy named Maurice Zuberano who worked on Citizen Kane as a sketch artist and was partners with Harold.

I started working with Harold on Throw Momma From the Train, where I wanted everything to be close and wide, so that the camera would distort the faces. We used mostly 21-millimeter lenses, sometimes 17. As a storyboard artist, Harold could show you exactly what you were going to see with each particular lens; before I got to set I knew where to put the camera and what lenses to use to give the characters that distorted feeling. I can’t emphasize enough how invaluable that was – Harold opened an incredible amount of doors in my head when it came to visual perception. He would draw things on napkins or whatever pieces of paper we had laying around, and then he’d go off and come back with choices that were off-the-charts great. He was very instrumental in inspiring the approach I used on War of the Roses, Hoffa, Matilda…everything that I’ve ever done.

Filmmaker: Well, my impression from The Ratings Game is that you were already leaning that way. The technique is very purposeful.

DeVito: It was similar, but in a much cruder way. I had conversations with my cinematographer about what I wanted and gave him some drawings, but my drawings are not like Harold’s – they’re indications of what you want things to look like, but not anything you would want anybody other than your D.P. to see. I actually haven’t seen The Ratings Game in a while now. I did keep the only print in my house – thank goodness, because the master for the DVD was made from it.

Filmmaker: It’s such a great snapshot of its era, partly because of the TV parodies within the movie. They’re hilarious, and they actually look like real shows of the period.

DeVito: They were so much fun to do. A lot of the credit for those has to go to David; he and I were both TV nerds at the time, and the shows came out of our conversations.

Filmmaker: The 1.33:1 frame works perfectly for those, but unlike some directors you’re not beholden to one particular aspect ratio. You’ve done great work in 1.33, 1.85, and 2.35 anamorphic.

DeVito: We discussed that a great deal on The Ratings Game and came to the conclusion that we wanted it to look like TV – that shape just jumped out right away as the correct choice. The War of the Roses was 1.85; I actually thought about doing it anamorphic, but I felt like I would feel less locked down with 1.85 doing all the fights and scenes where they were chasing each other. I had a masterful cinematographer on that movie, Stephen Burum, and when he and I did Hoffa we felt like we could have a little bit more majesty, so we went with anamorphic.

Filmmaker: Something The Ratings Game and The War of the Roses have in common is a really nice tonal balance, where you have different levels of comedy and drama in the same movie. Everybody remembers War of the Roses as this kind of heightened black comedy, but there are scenes in it that are like something out of Bergman’s Scenes From a Marriage! And in The Ratings Game, you have broad satire coexisting with a genuinely sweet, realistic love story between you and Rhea. How do you juggle those tones?

DeVito: I guess it’s mostly instinct. I just approach everything in a real way and don’t put any boundaries on it – when I shift from one type of comedy to another, or from comedy to drama, I don’t think of it as another direction. I just follow the characters and commit to where I think they would go. Although I always start out thinking of a movie in visual terms, ultimately I prioritize the actor; I love beautiful shots and making the D.P. happy, but I never want to compromise the actor or actress in any way. You have to protect the performers and not leave them with the proverbial egg on their face, even if that means sacrificing a take where the light was perfect or something like that. As you noticed, I do plan my shots very precisely, but I also have lots of conversations with the actors about what I’m envisioning so that they can contribute to it. I usually give them an area to work in, which is what Milos Forman did for me on Cuckoo’s Nest – he would say, “Martini, this is your place, this is your spot. You can operate naturally and be free in that space.” I do the same thing for my actors, I give them a space and let them be as realistic in that space as they can be. Then they don’t have any shackles on them and they can feel free to explore. On the show I do now, It’s Always Sunny in Philadelphia, there are three cameras; you set them up and do it a million times. Sometimes we stay with the script, sometimes we improv, then in the editing room there a lot of ways to go.

Filmmaker: Speaking of editing, I would think that after you look at the same material over and over again in the editing room it might be difficult to maintain perspective on what’s funny. Do you do a lot of test screenings on your movies to see how audiences respond?

DeVito: Oh yeah, I think it’s really important. I always get a kick out of people saying they have final cut, because even when you do you really don’t. It’s up to the audience – you listen to where they laugh, you get a sense of their relationship to the material and the characters…if you’re lucky, you have to add frames where people are laughing so much that they can’t hear the last line. If you’re not lucky, you’re taking stuff out because it isn’t funny. War of the Roses was interesting because a lot of people related a little too closely to the movie – they were seeing their own marriage in it, and that kept giving us mixed messages on the tests. I could never get the score where the studio wanted it. We just had to be happy with it ourselves and release the movie, and luckily it worked out really well. Throw Momma From the Train was more straightforward, whereas you wouldn’t believe some of the stuff I was hearing from people who gave War of the Roses bad scores because they were relating it to their own lives. Matilda was fun because I really got to see the kids; I put a camera in the front of the auditorium and watched the faces of the children, which was very revealing.

Filmmaker: You seem like you take so much joy in this process, and I find it interesting that now you’ve gone back to where you started, making short films again.

DeVito: I just did a movie called Curmudgeons that we shot last October. My daughter Lucy, who’s an actress, and my son Jake, who’s a producer, went to this one-act play at the Ensemble Studio Theater with me a few years ago and Lucy said, “This would make a great little movie, and you could play the other part.” The main part was played by a friend of mine, David Margulies. We got the writer, Joshua Conkel, to adapt it, and we shot it in three days – it’s such a great feeling when everybody gets together and helps out and you just do it. It was at the Tribeca Film Festival, and we’re going to the London Film Festival, and in a month or so we’re going to release it theatrically in L.A., probably at a Laemmle theatre. Then we’ll probably put it out on Vimeo. I love doing short films, because it keeps you going – you’re working, you’re shooting, you’re editing – it’s tactile, and it’s so much fun! Working with your friends and family…what a wonderful experience.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and iTunes. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.