Back to selection

Back to selection

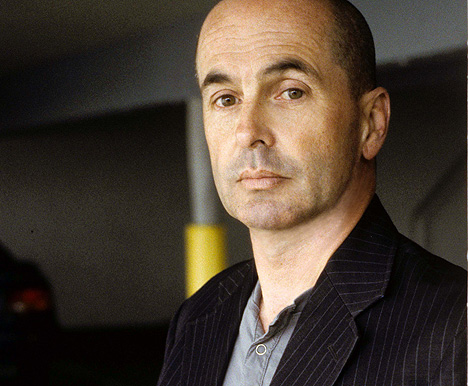

Don Winslow on Savages

“Fuck you.” With those opening words of Savages, author Don Winslow delivered a kick to the teeth of the literary world. The jarring and unorthodox novel — about a trio of beach bum lovers-turned-drug kingpins and with a writing style that ranges from poetry to screenplay — became a New York Times Bestseller and a shot in the arm to Winslow’s already successful career. The author had penned more than ten novels prior to Savages, including the Neal Carey series, while moonlighting as a private investigator during grad school and the meticulous DEA/drug cartel fueled intrigue of The Power of the Dog, but Winslow describes this novel as a “big risk.”

With Savages‘ abrasive opening, left-of-center writing style, and atypical central trio, Winslow wasn’t even sure the book would get published. Luckily for him and us, it did. Winslow notes, “It’s worked out great! And the editing process was relatively easy and I thought they’d be on me like ugly on an ape! And I thought that first chapter was gonzo. But here we are.” Sitting with Winslow, lounged across a conference room chair with a trickster’s smirk across his face, it’s easy to see the well-earned pride that the man has in his work and its growth but the glean in his eye and the constant kineticism belies something more. This is a man never content. Never content to rest on his laurels; to stop and admire the stories already told, the paths already taken.

One of Winslow’s latest paths has brought him to the attention of another crime genre maverick: director Oliver Stone (Natural Born Killers). With Stone at the helm (of which Winslow says, “It’s everything you think working with Oliver Stone would be. It’s intense.”) and his longtime friend Shane Salerno tackling the screenplay alongside him, Winslow embarked upon adapting Savages for the big screen. The fruits of their labor hits theaters this Friday. Filmmaker talked to Winslow about the book, the movie, his newly published prequel The Kings of Cool, and his relationship with the cinematic medium.

Filmmaker: Getting a little background on Savages, why did you decide to write this book?

Winslow: I’m not trying to be coy or clever, OK? The answer is, I don’t know. I sat down in a very ugly mood; typed out two words: “Fuck you.” And that was the first chapter, and has sort of become the infamous first chapter that I have to live with. Then I sat there and I thought, “Well OK, wise guy, you’ve done that; you got that out of your system. But what about it?” I literally had no story, no idea, no nothing. And I just started typing, and all of a sudden I find myself writing in the voice of this 20-something Orange County woman — which, you know, I’m not [laughs] — talking about her lover who is sitting behind a computer and is cleaning a gun. So I thought, “OK great, but what about that?”

Several weeks prior to that I had been sent an email of a video clip of seven decapitated bodies. Because I had done a book about the drug cartel a number of years before [The Power of the Dog] somebody thought it appropriate that I should see this. And that got me thinking about the sort of fractured way we all communicate these days, you know. Your generation, frankly.

You’re all schizophrenics, I don’t know how you do it — a vid clip now seems like a longform kind of thing and I wrote this freakin’ book two years ago, right? Now it’s tweets, and this, and that, and everything’s coming in so fast. And so, that kind of reminded me of decapitated heads, you know? I mean, Skype. We’re literally severed heads floating in space. And so all that sort of started to come together.

Filmmaker: A lot of writers might have the story all planned out ahead of time, but it sounds like that was very much not the case. Is that normally how your writing process goes?

Winslow: More or less. Sometimes I do an outline, but what I tend to find, even when I do, is somewhere around page 70, give-or-take, the character will do or say something that wasn’t in the outline; but it’s better. And then I go chase that, grab it for a while.

So I think, you know, if you back out of the driveway it’s probably a good idea to have some idea of where you want to go. But I don’t want to be married to that concept.

Filmmaker: It sounds like it is very much a character-driven style where you have these shapes come up and then have them dictate where the story’s going to go.

Winslow: Yeah, you’ve just put it better than I ever have — I’m a little sad about that. [laughs] Listen, you can come up with a plot first. I never have but I guess you could. But then what I’m afraid happens is you’re just creating characters to fit into those slots and I don’t think it’s as real or as rich as it could be if you go the other way around.

Sometimes I think, “OK, I want to write about this world.” The drug world, the mafia world, the whatever world. But the very next thing I’m going to do is character and location; I sort of think they’re inseparable really. And then, I think if I get the characters and location right, then the characters are going to do the correct thing. They’ll make the choices that are best for the story.

Filmmaker: These characters — particularly the main three of Ben, Chon, and O — have a really unique dynamic between each other. What was the inspiration for these characters and how they relate within their world?

Winslow: Well, look, I’ve inhabited that world. I lived in Laguna Beach, Dana Point, I still live on the Southern California Coast, beach town. And so I know these cats. There are no particular individuals that inspired them, but I could take you to Laguna tomorrow and we’ll show up and they’ll be, you’ll see, Bens and Chons and Os playing volleyball right there on that beach. You just will, I can flat-ass guarantee it.

In terms of their triad? I think that I wanted to flip the usual relationship, you know? If you see that typically in film or in novels it’s the guy and two women. And he’s cool because of it. Nobody calls him a slut, nobody calls him a whore, you know? So, I wanted to have a woman character do that. I wanted a woman character who was unashamedly in charge of her own sexuality.

Filmmaker: It’s an interesting interplay because she’s a very compelling character and at the same time the two guys are completely in the element of it and not emasculated by it at all; which you think might be the conventional wisdom of “How are these two guys OK with being in this situation?”

Winslow: Yeah, I mean, listen, not to blow my own horn, but I think it’s interesting. But fluid. If the book had ended other than what it had, I don’t know what the situation might’ve been six months down the road. I think they’d always be close, but I think the relationships may have shifted to where she might not be romantically involved with either of them. Who knows? But what I do know is those three characters love each other and form a kind of a family that they otherwise don’t have.

Filmmaker: Obviously not wanting to spoil the book for anyone who hasn’t read it — or the movie for viewers — but was it a shock to you when the book ended that way? How did it feel when it came to that sort of conclusion?

Winslow: I’ll be very honest with you: it was a tough decision to make. The rest of the book was relatively easy to write—easy as books ever are which is not. I really, really debated on it, long and hard. And then I just thought it had to end that way. I think what they’d experienced, what they’d become, they couldn’t go back to what they’d been in any believable way. And I think that that was, unfortunately, the natural consequences of what had gone on.

Filmmaker: Another thing that’s very unique about this book — as well as the prequel, The Kings of Cool — is the writing style, the use of syntax, and even having some scenes written in screenplay format. What was the inspiration behind using that sort of style?

Winslow: I’m a genre writer, crime genre writer. I was starting to feel defined out of existence. Do you know what I mean? The walls just keep closing in, man, on what you can do in these alleged subgenres. If you’re a “thriller writer” than your character has to be in mortal jeopardy on page 1. If you’re a “soft-boiled this”, or a “hard-boiled that”, or if you’re a “procedural” then [pantomimes walls slowly squeezing in].

And I felt, at some point in time, you’ve got to throw some elbows, you know? You’ve gotta give yourself a little space. And obviously with a beginning of a book like that, I was in an ugly mood anyway and I thought, “You know what? I’m just gonna write this fucking book the way I hear it. The way I see it. And if people love it, great. I hope they do. And if people hate it, then they’re gonna have to hate it. But I’m just gonna do this.”

And, you know, the scenes in screenplay were written that way because I thought, for that scene, an audience would get it better as a piece of film; as close as I can get to it in a novel. In other scenes, they get it better as narrative fiction; in other scenes they get it better as poetry. I think that’s true. Maybe it’s just the way that I saw it or just the way that I heard it in the moment of thinking, “Fuck it, I’m just gonna write it that way.”

Filmmaker: You had been sort of reluctant in the past to get more directly involved in film adaptations. What made you decide to take a more hands-on role this time around?

Winslow: I saw the first film of one of my books.

Filmmaker: You just decided, “I have to stop that”?

Winslow: It was a four-hour drive home from the screening and that gave me a lot of time to think. The truth is, I didn’t expect it to hurt as much as it did. There are two sort of broad streams in novelists in regard to film. There’s the “throw the check over the fence and I’ll run,” which had been my previous attitude, and then the other one is “I want to get involved.”

So, I took the previous approach and I saw what happened. And I also saw that of the major problems that film had, four out of the five had been problems that I had alerted them to. They said, “No, no, you’re a novelist. We’re filmmakers, we know better.” That was exactly the response; and I believed them. Because it’s a logical argument, isn’t it? You go, “Yeah, you know what? They are filmmakers and they probably do know better.” Not necessarily.

And so, then I teamed up with Shane Salerno. Very, very prominent and a fantastic screenwriter; and we would talk about these things because we’re buddies. And then finally he said, “Why don’t we get together? You know, and let me sort of guide you through this stuff.” So now I’m taking, and will be taking, a much more hands-on approach. Which is not to say I ever have the delusion that I’m going to have 100% control. It’s a cliché, but at the end of the day, it’s the director’s movie. But I do want a real seat at the table. And part of that involves co-screenwriting some of my stuff, other parts will maybe be involved with co-producing some of my stuff; depends on the project. But yeah, I think that’s where salvation lies.

Filmmaker: The transition for any book going to film is pretty much always difficult and there are things that have to be changed. Were there any major changes from the book that you felt wouldn’t work in film and had to be edited for the movie?

Winslow: Yeah. Look, it’s funny, film people tend to talk to novelists like we’re the slowest kid in class. They literally slow down to talk to you and they look at you and say things like, “You know…books and film are two. Different. Media.” Really? I didn’t know that. Huh? Damnit. [laughs]

And what I want to say in response sometimes is, “Guys, two thousand years before you guys were editing, we were editing.” You know? I get it, so when it looks like, “Oh, it’s gonna be a movie and I’m going to have a part writing it,” and all that fun, albeit scary, stuff I already knew that there were things that had to be changed. And I could tell you what they were, you know? And I brought some of those changes to the table.

Filmmaker: In my opinion, it’s sort of a trap because the book almost always seems to be much better than a derivative film. I think a lot of it has to do with the fact that it’s hard to capture the same amount of detail and plot in a shortform feature, so it takes a really special team. Do you think you achieved that?

Winslow: I think we did a good job. Do I agree with everything? No, but you’re never going to because you’re looking at a guy who’s written fifteen novels and that’s the way I see the world.

But again, I think that audiences and readers need to be aware that these are two different media, you know? And readers of any book, particularly sort of the “cult” books, always come away with that, “Well, it wasn’t the book.” Well, of course it wasn’t the book, and the book wasn’t the movie, you know? I think that’s sort of to me the underdiscussed difference between the two medium: reading is such a personal experience and film, at the end of the day, is a group experience. You know? And should be.

And so, readers of, I don’t know, Game of Thrones, or Harry Potter, Hunger Games, whatever it happens to be, I think, develop these ferocious loyalties to their internal image that they have of that very deeply personal experience they have with the book; and then they are almost always, invariably disappointed when that vertical, kinetic image doesn’t match what’s been going on inside their head.

Filmmaker: The Kings of Cool just came out. What made you decide to revisit these characters?

Winslow: I picked up their trajectory very near the end of it — and that was a deliberate choice — but I always knew the rest of the story. One reason that I hope that they come across as fully-formed characters in Savages is that I knew every other moment of their lives before I picked them up; and their parents’ lives and the culture that they came from. And so people seemed to like these guys and be interested in how they got to be who they were. I knew the answers and I guess I wasn’t finished with the story yet.

The bigger answer is that I wanted to write a book more about America in those years. I wanted to write about not only how Ben, Chon, and O came to be who they were, but how did we come to be who we are over those decades.

Filmmaker: And there’s something of the sense of the characters mirroring their parents, but at the same time fighting against it—which is sort of an archetypical trope. How much of a part do you think that played in the story?

Winslow: Oh, I think it played an enormous part. I think that there’s no arguing with DNA and in a certain extent, I think it’s the story of everyone’s life; the struggling with one’s past, one’s family for good or for ill. To achieve a certain independence and at the same time a certain unity with that, I think that’s everybody’s trajectory.

I think it’s the country’s trajectory as well, you know? I think that you live with a national mythology and a national reality which at some point as a country you have to cope with.

Filmmaker: Do you have any other plans for film work right now after Savages?

Winslow: Yeah, Shane and I just finished another adaptation of another one of my books, called Satori, that Leo DiCaprio’s doing. And then Chuck Hogan and I are writing an original film story together. I love The Town and I love Chuck’s work and we’re both New England boys.

You know, at the end of the day, I’m a novelist. That’s where my home is, that’s where I live. So, there’s three books right now that I’m writing and excited about. And these other film projects as well. Life’s good.

Filmmaker: To wrap up, what are some films and books that have inspired you?

Winslow: Well, damn, how much time do you have?…Let’s start with film. I think, in my genre, my favorite crime film is The Friends of Eddie Coyle. If you haven’t seen that one, you need to. Go out this afternoon as homework. The Criterion Collection has a great one. Everybody lists The Godfather and I will as well.

Books? God, there are so many of them. All of Shakespeare, who I think might have been the first great crime writer — The Godfather is a retelling of Henry IV. Also with writing the book of Savages I took a really close look at the new wave guys from the ‘50s and ‘60s. I mean, quite obviously, Jules et Jim given the relationship with these three people I thought I better take another look at that.