Back to selection

Back to selection

Alternate Routes: New DIY Distribution

As the keynote speaker at the Los Angeles Film Festival this June, Chris McGurk, of digital theatrical distribution platform Cinedigm, described seven signs of a resurging indie film industry — an “indie renaissance,” he called it. Most of his bullet points had to do with the ways in which digital technology and social media allow for new ways to program for and reach audiences in theaters and online. “Just as happened in the ’80s,” he said, “there is an exploding demand for filmed entertainment. There is huge competition now going on between all of these digital retailers. It’s an ‘arms race’ to ensure that each one has a high quantity of high-quality content to drive viewership, whether ad-supported, subscription-driven or transactional. This dramatically increases the demand for content, including indie film. And this time, because this demand is driven by digital, we are seeing the rise of distribution strategies that are as creative as the content.”

Of course, McGurk is coming at this new digital distribution thing by way of the executive suite. A former Pepsi exec, McGurk previously held top positions at Universal, MGM and Overture, and his new company, Cinedigm, is an almost $100-million a year business that has acquired key players in the independent space, like New Video, which it bought this past spring. As a cross-platform company, Cinedigm has the punch to propel its content across all those different platforms — as well as to diversify away from film entirely by distributing content like the World Cup to theaters.

But what of the filmmakers in the audience? Are independents without large market caps finding ways to experience this “indie renaissance”? The points outlined by McGurk have been echoed by scores of distribution gurus, many of them in these pages. Has a new way of thinking finally begun to take hold?

Actually, yes. Amidst all of this innovation, the learning curve has begun to level off. Not only are enterprising do-it-yourselfers increasingly taking distribution into their own hands, but they’re communicating with each other and even inspiring a small cottage industry of authors, advisors, companies and nonprofits, all angling to help filmmakers deliver their work to a paying public. The technological means used to do this will keep evolving, of course, but some guiding principles will continue to hold steady, chief among them that filmmakers need to prioritize their goals for every production and tailor the release accordingly. The following three films represent very diverse cases, each calling for a unique, self-motivated distribution campaign that rethought the definition of “theatrical,” leveraged social media and altered the flow of traditional distribution windows.

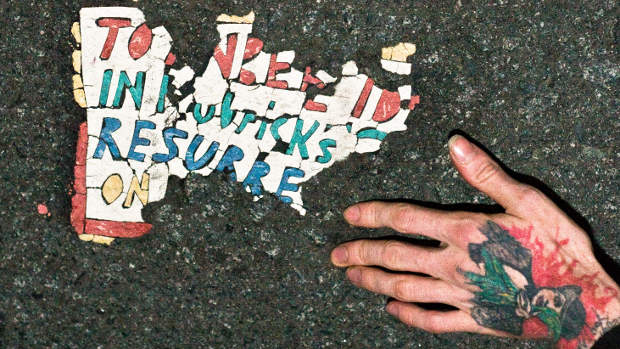

RESURRECT DEAD: THE MYSTERY OF THE TOYNBEE TILES

Director Jon Foy’s Resurrect Dead: The Mystery of the Toynbee Tiles documents the urban lore surrounding a group of cryptic messages written on tile and tarred onto the asphalt of Philadelphia and other cities since the early 1980s. It’s a personal, psychological film that Foy stumbled into nearly by accident when he prank-called tile expert Justin Duerr. His interest was piqued, however, and over the next several years he shot Duerr’s personal quest to discover the origin of the tiles, piecing together clues as diverse as a Jupiter colonization cult and David Mamet’s short play 4 A.M. Supporting himself as a house cleaner throughout the production, Foy used whatever equipment he could and never gave a thought as to how he would package the finished product. “I was just trying to make the film. Distribution wasn’t even on my mind.”

That changed when Resurrect Dead was accepted into Sundance in November 2010. Not knowing what to do next, Foy asked for advice on the documentary networking website The D-Word and caught the attention of D-Word founder Doug Block. Block, also the director of such docs as 51 Birch Street, wound up coming on board as an executive producer. Together Foy and Block came up with three goals for the campaign they’d begin at Sundance: first, to make a profit; second, to maximize the number of markets they played the film in; and, third, to get Foy discovered as a filmmaker.

Establishing goals like these up front can help all the other pieces fall more or less into place. Block, who sees a lot of projects, advises, “Be realistic and think long term. Overnight successes are going, going, gone. Think in terms of what success means for you on a smaller scale. Think of your whole career, not just a single film. In the digital world, it’s all about people discovering you.”

Foy’s first order of business was getting the film ready for the festival. Since he was working on near-antique equipment he wasn’t even sure he would be able to get the file off his computer. He managed, though, and the first of what would be many sets of deliverables — a Sony HD Cam master for the Park City screening — was sent off. Meanwhile, because maximizing a festival screening is expensive — and despite a Kickstarter campaign earning more than $13,000 — Foy had to go into debt just to cover costs.

In order to earn back those monies and maximize future revenues, Foy and Block knew they had to retain a sales agent, so they showed the film to Josh Braun of Submarine Entertainment. Remembers Braun, “We were looking for films to take to Sundance, it came in the office, and it was incredibly intriguing and unusual. It was a little bit of a question mark commercially, but we thought it almost played like a thriller. So we took a chance on it just because of how different it was. After we saw it [but before the festival], the film was tweaked a bit in the direction of creating more mysteries. And when it went to the festival, certain companies thought it was an unusual, strange little film.”

Resurrect Dead played well at Sundance, garnering good reviews and buyer interest. Says Braun, “We went into the awards [ceremony] with a few possibilities — nothing huge, but two or three midsize to smaller [theatrical] distributors. And then there was Focus, who had this thing that wasn’t public yet.”

Foy wound up winning the U.S. Documentary Directing Award, and that “thing” was Focus World, the specialty distributor’s new “digital distribution initiative.” Says Braun, “We could do a deal [with Focus World] that excluded television, which was positive, because we had [premium cable channel] EPIX interested, and they were going to pay a decent amount.” However, missing in all of this interest was a theatrical component, traditionally the dream of independent filmmakers. What’s more, the deals on the table demanded release windows before any theatrical could occur. How did Braun present the no-theatrical deals? “Jon is a young filmmaker,” says Braun, “and he didn’t go into Sundance with a lot of expectations. But the pitch to him was, ‘Focus loves your film, Focus World is a new venture of theirs, you’ll have access to the Focus button on Amazon and iTunes, and you’ll have the prestige of being promoted alongside Brokeback Mountain. [Resurrect Dead] won’t be distinguished separately. You’ll have the benefit of all those other channels.”

After the awards, Braun closed the EPIX and Focus deals. Focus Executive Vice President of Business Affairs, Strategic Planning and Acquisitions Avy Eschenasy says, “Resurrect Dead was something we were thrilled to be involved with. Not only is the film itself unique, compelling and fun, but the story of how Jon got it made and into Sundance is something that, as we were beginning Focus World, made it an even more perfect fit. We included the film on VOD platforms with conspiracy-themed films from our library such as Burn After Reading, Brick and Mulholland Drive, which enabled the film to reach a broader audience.”

The next step was to figure out a way to get the film in theaters. “The filmmakers wanted to do it,” Braun says, “and I thought it would be valuable.” Is that always the case? Are some films best left undistributed to theaters? “There’s always that element,” admits Braun. “If you think of a film as a theatrical film, you have to be self-aware that it may not be breakout. [You want it to] get positioning and not crappy reviews, which happens all the time. Ten out of 20 films that are [self-released] are pointless exercises in self-promotion and vanity. Just look at The New York Times each Friday. But the reaction to this film was positive, and I knew it wasn’t going to be one of ‘those films.’”

A theatrical release, even a “traditional” one handled by an outside distributor, takes a lot more filmmaker involvement than 10 years ago. Block, who sees a lot of filmmakers weigh theatrical’s worth, says, “I think docs are made to be seen in a theater. But you have to create a strategy; it’s important not to go into a theatrical release thinking it’ll make money.” So is theatrical always the right choice? “It’s a terrible time for theatrical,” he admits, “but for young filmmakers, we’re not at a stage yet where you can just put your film up digitally and get discovered. You still need theatrical. You need that to make a name for yourself.” If you go the other direction and “go straight to audiences with digital, you’ve got to be really smart to break through all the clutter online.”

So Block and Foy brought on Jim Browne of Argot Pictures to handle a small theatrical release. Argot typically works on a service basis in partnership with the filmmakers and is known for crafting economical campaigns that target both theatrical and nontheatrical venues. “Generally I put together a [distribution] budget for the filmmakers, and in my budget is a small fee for Argot,” says Browne. “Those budgets can range from a low of $10,000 to a high of $75,000. Typically we are guaranteed three months of fees and we do a 50/50 split on what comes back [from theater rentals]. Our fees vary based on the budget and size of film, but they range from as low as $1,200 a month to $3,500 a month. And we don’t participate in the digital or TV sales.”

The budget Browne gave Foy and Block was $19,000, and it required them to front half, with the other half budgeted to come out of revenues. (With the knowledge that the EPIX deal was closing, Browne actually wound up fronting some of the required expenses.) While this was going on, Foy was also struggling to deliver the picture. The EPIX deal alone took six months — and didn’t pay out until November — and Foy said he found the enormous number of deliverables by Focus overwhelming. But, he says, “They worked with me. My computer was on its last legs and I was able to tell them, ‘Here’s my situation.’” Block adds, “They got it when we said, ‘Look, your contract is for Brokeback Mountain and we’re Resurrect Dead.’”

Browne’s original plan was to book screenings in New York at the IFC Center (its vice president and general manager, John Vanco was a fan), Philadelphia (the filmmaker’s home town) and one other city. Philadelphia’s run was five nights at a nontheatrical venue, the International House, which, aided by Foy’s appearances, sold out. Boosted by great reviews, other bookings followed, including the Oklahoma City Museum of Art, the Utah Film Center in Salt Lake City, Downtown Independent in Los Angeles and a run at Facets in Chicago. In fact, the film is still playing, with 32 bookings listed on the Argot site. Most of these bookings were for a guaranteed fee — $300 was typical — against 40 percent of the box office. When Foy appeared, he’d often get a $250 appearance fee, plus transportation.

Resurrect Dead kicked off its theatrical campaign in September 2011, but it was available through Focus World and on VOD a month before that, in August. Many times that’s the case today, says Browne, and it fits into his strategy. “I’m starting to work with filmmakers earlier, looking at the whole distribution chain and planning it all as one piece, often with digital in advance of theatrical,” he says. However, he continues, “Exhibitors are still nervous about having something online ahead of theatrical. Day-and-date is a large hurdle. Theater owners don’t like it because it’s not traditional.” Block says he believes the publicity spilling over from a digital release can help a film, but Browne isn’t always convinced. “I didn’t agree with that being a helpful thing,” he says. “I do most of my business dealing with theater programmers and bookers. Day-and-date is more of an impediment than a sales pitch.” Still, it has its benefits for the overall campaign, as Block notes, “Jim booked a ton of places for theatrical, and then people discovered it on digital.” The film also was released on DVD through Focus after its initial theatrical play.

By the end of June 2012, Resurrect Dead has grossed $27,662 from theaters. In its annual analysis of industry revenue, Film Comment characterized the film as a loss maker for Argot, but Block counters, “It’s been one of the most successful films of the past year on its own terms. It’s one of the really big success stories that’s gone under the radar.” Indeed, box office is no longer a tell-all metric. “You’d think Indiewire would stop publishing box office,” Block says. “We spent $17,000, and we projected $19,000. We not only got that back, but it’s booked into the foreseeable future.” Browne adds, “The EPIX and Focus deals were lined up initially, and it’s already up on iTunes and VOD. And I continue to book it for theatrical.”

Resurrect Dead’s earnings may be well below Fahrenheit 9/11’s, but the film’s carefully crafted release and digital deals succeeded in fulfilling the team’s initial goals. Foy’s movie has made a profit over production and distribution costs, with more revenue continuing to come in; it has had a broad theatrical run including stand-alone screenings and festivals like Hot Docs, Silverdocs and Full Frame; and it has gotten Foy out of the house cleaning business. In addition to his unusually involved process creating new deliverables—“I know more about the frame rate conversion for delivering to Israel than any other director I know,” he jokes—and touring with Resurrect Dead, he’s now writing a fiction feature and working on another feature doc. A respectable showing for a one-man film about conspiracy theories and street art.

UNFINISHED SPACES

Alysa Nahmias’ and Benjamin Murray’s goals for their film Unfinished Spaces were quite different. The film grew out of a visit Nahmias made to Havana in 2001 in which she toured Cuba’s National Art Schools, a crumbling, unfinished campus of modern brick buildings commissioned by Fidel Castro and Che Guevara in 1961. She and Murray got to know the site’s three architects, Ricardo Porro, and Roberto Gottardi and Vittorio Garatti, learned how they had been exiled from Cuba in 1965 for their work, and saw how the decaying schools stood as a metaphor for the entire Cuban revolution, “from utopian vision to tragic ruin, and ultimately to an uncertain future.” They knew they needed to put this story on film “to expand cultural dialogue about Cuba and to shine a spotlight on the promise and challenge of international historic preservation efforts.” Any desire to recoup costs or build a following for the filmmakers were secondary to this social agenda.

Having this goal helped them win the trust of their subjects in Cuba throughout their 10-year production and has informed all their distribution decisions since then. As the directors explain, “We had hoped Unfinished Spaces would bring people together on both sides of the Cuba issue. For example, the architects who are the subjects of the film have received standing ovations at film festivals in both Cuba and Miami, which wouldn’t have happened 10 or 20 years ago; it’s a sign that a new generation is more open to listening to others’ perspectives.” While these screenings have been rewarding, the film might have an even more tangible impact on its subject. As Murray said in an interview this spring, “The schools’ restoration is something that’s really in flux . . . We’re hoping that this film can draw attention to it, and who knows? Maybe the schools will be getting restored again soon.”

The film’s first milestone came in December 2010 when Nahmias and Murray sold the television rights to Latino Public Broadcasting, a Corporation for Public Broadcasting-funded nonprofit that focuses on issues relevant to Hispanic Americans. Though the film won’t have its PBS broadcast until this October, this first sale marked the path of finding outlets that would target the Latin American community. The premiere was held at the L.A. Film Festival in June 2011, and instead of seeking a traditional sale Nahmias and Murray viewed the festival as the beginning of a now two-year public-screening tour, which, so far, has included events like DocuWeeks in August, the Havana Film Festival in December, the Miami International Film Festival in March, and 17 others by July. During the Miami fest, the filmmakers increased their outreach via a master class at Miami Dade College, a Cuban art exhibition at the Freedom Tower downtown and a free screening to 400 high school students from the Miami-Dade school district.

“The Havana screenings were extremely emotional,” say the directors. “Our favorite response was from a middle-aged woman who said, ‘I can’t believe two filmmakers from North America made a mirror for us to hold up to ourselves.’ There were many tears of pain and joy in the audience as well. It really felt like the film came full circle and had a bigger impact than we could have imagined.”

But the filmmakers knew they wanted to move beyond the festival circuit to reach the rest of their desired audience. Their second milestone, therefore, was being selected for Sundance Institute’s Film Forward program, an initiative that fosters cross-cultural dialogue about social issues. Under this aegis Murray traveled with the film to Beijing and Kunming, China, where viewers felt a powerful connection with the Cuban storyline. The film’s third and most important coup, though, was winning the Jameson FIND Your Audience Award at the Spirit Awards this January. In order to apply for the award, the team had to outline a distribution plan and for this they devised a nontraditional one that proposed targeted community screenings in nontheatrical venues instead of a more conventional plan of one- and two-week runs in typical New York and Los Angeles arthouses. The Jameson Award came with a $40,000 grant, which proved essential as it allowed them to retain marketing and distribution company Film Sprout to handle the rest of their grassroots campaign.

The connection with Film Sprout was not accidental. Being aware of the company and the Jameson award, Nahmias and Murray had met months earlier with its president, Caitlin Boyle, secured her help to craft their proposal and attached her name to their plans. Now with the money finally in hand, they were able to formalize their collaboration and plan an extensive public screening effort that will roll out this fall.

Says Boyle about Film Sprout, “What we do is help filmmakers who are trying to pursue alternative distribution. We focus on films that have the power to capture a particular audience, and often that means a film that has a particular call to action from a social change perspective. Or a film like Unfinished Spaces that is covering a topic for the first time and is going to energize a particular audience and bring them together. With most films, we organize a large number of public-facing community screenings in a five- to eight-month period right after a film is off the festival circuit or its initial theatrical run, and we book in alternative venues. Some are universities and museums and some are unconventional, like vacant lots, corporate boardrooms, cruise ships and army bases.”

She continues, “We work on a retainer and all revenues go to filmmakers, and we only take on projects that have a big enough reach that we can get to a high volume of people in a short period of time. Our goal is that the money out to the filmmaker be greater than the money we have been paid.”

For Unfinished Spaces, Boyle and the filmmakers created a “showcase tour” with large upcoming events in New York, Tampa, Miami, New Orleans and Union City, New Jersey. The venues range from Cooper Union in New York to a Cuban social club in Tampa to Tulane University in New Orleans. These screenings, in Boyle’s words, “will enable us to attract a true cross-section of audiences from the Cuban-American community, the architecture and design community, and the historic preservation and public humanities community. Our aim is to create multidisciplinary, dynamic, diverse forums where individuals and organizations who don’t normally find themselves together in the same room can come together around the film, engage in a refreshing and open public dialogue about its themes, and experience a beautiful, artful film outside the confines of the film festival or theater. The showcases will also build an audience for the broadcast and a market for the film’s release on educational and home DVD.” The costs of mounting the showcase screenings, the associated travel, the Blu-rays, Film Sprout’s fee, a Spanish-language publicist, publicity and the production of discussion materials will be covered by the Jameson grant. In addition to the revenue generated by these screenings, other revenue for the filmmakers will come via dozens of smaller screenings in other cities, in venues such as schools, architecture firms, art shows and conferences.

Without Film Sprout, Unfinished Spaces’ public screenings would now be winding down, instead of, in the filmmakers’ words, “going strong nine, 12 and 18 months after the world premiere.” So what did Nahmias and Murray do to make their project so attractive to Boyle? For starters, they formed a strong connection with their potential audience. Boyle says, “Filmmakers who have paid close attention to—and have organized and recorded feedback from—the audience groups that are attracted to their film are enormously helpful to us, as they can provide market research that is otherwise hard for us to gather firsthand. This is more difficult than it seems, because it takes attention and organization to record every phone call or email you might have received as your film made its debut at film festivals or in initial premiere screenings! But that kind of information gathering is invaluable.”

Boyle also praises Nahmias and Murray for their “real, lasting, personal relationships with stakeholders” in the National Art Schools. “A filmmaker who’s deeply connected to his or her subjects and experts typically has much to add to the initial outreach efforts that Film Sprout does, because he or she can introduce us to people who are best poised to help us understand the film’s audiences: where they live, what they do, how they have received the film thus far. In turn, those experts or subjects can point us toward the most strategic avenues for reaching their own communities. In the case of Unfinished Spaces, Alysa and Ben’s connections with leaders in Cuban-American cultural history, architecture, and historic preservation circles have been instrumental in helping us fast-track our outreach efforts.”

Many of those connections came because Nahmias and Murray recognized they couldn’t create—or release—the type of film they envisioned on their own. In fact, they claim soliciting help is the most important thing a filmmaker can do to promote a film. “First, be humble and wise enough to ask for help. Whether it’s logging onto the D-Word for some late-night camaraderie, or calling up experts like Caitlin Boyle, Peter Broderick or the folks at Film Independent, Sundance Institute, Women Make Movies or IFP, you need to know what you don’t know about distribution, and determine when to ask those who are in the know. Also, the flipside of this is that we as filmmakers must be generous with our own knowledge. The more we share and cross-reference with each other, the better off we all are.

“Second, you cannot do it alone, but neither can they. Delegate the tasks that your distribution partners can do best and with passion. Arguably the best money we spent on this entire film after it was finished was to hire Amy Grey at Dish Communications to be our publicist for the Los Angeles Film Festival and DocuWeeks. Amy loves this film as much as we do, and we knew that as soon as we got her call. Without Amy, we don’t know how Unfinished Spaces would’ve reached its audience.”

DAYLIGHT SAVINGS

When rising writer/director Dave Boyle finished Surrogate Valentine in 2010, he wanted to keep the filmmaking experience going. The picture starred indie musician Goh Nakamura as himself and expanded Boyle’s range beyond the quirky comedy of his first two films into more mainstream indie fare. The film played fests, had a small theatrical run and went out on VOD through Warners. “Goh and I had a good time together, it seemed like the story could continue,” he says. After their SXSW premiere they carved a few weeks out to shoot a sequel, and the resulting film was Daylight Savings, a black-and-white drama that showed at this year’s SXSW and is currently in the middle of its distribution.

Boyle had a few simple goals for the project: to keep working with friends from Surrogate Valentine, to “build something we could all be proud of,” to “grow as a filmmaker and try things that I hadn’t done in my first three films,” and to “experiment with the concept of a mini-franchise.”

The concept of creating a franchise—not just a sequel—was particularly compelling. “I wanted to see if we’d increase our audience going from film to film, if it would plateau, or if the audience for Daylight would be a fraction of Valentine’s.” The jury’s still out on this, but the franchise-building mentality allowed the team to think beyond a single narrative film and lean toward a transmedia, or at least multimedia, storyworld. In addition to the films, the team has created a combined soundtrack for both pictures and a nonfiction Web series featuring Nakamura talking to different musicians, with the potential for a third feature as well. This approach also prompted Boyle and his team — Nakamura, writer/producer Michael Lerman, and executive producer Gary Chou — to deprioritize traditional channels of distribution, like theatrical, in favor of more intimate ways to connect with their growing audience. “Social media has made the world a smaller place,” Boyle says, “and it seems that potential audiences and investors need to feel a direct and personal connection to the filmmaker in order to take the leap and choose to watch or support an independent film over the other entertainment choices they face.”

Without any type of distributor at all, the team needed more cash to take the film to additional screenings. So they hit upon a way to obtain funds while simultaneously fostering a personal relationship with their audience: to use Kickstarter to not just fundraise for screening and touring costs but as one of the film’s chief distribution platforms. They launched a campaign that offered copies of the film as rewards—with no other way to purchase it anywhere else online. A $15 donation received a digital download of both Surrogate Valentine and Daylight Savings; a $25 donation added a DVD of either film and the combined soundtrack; and $45 included DVDs of both films.

The Kickstarter campaign surpassed its $8,000 goal by $1,730, with 56 backers pledging $15 for the downloads, 60 backers pledging $25 for one DVD, and 30 at $45 for both DVDs (only six people gave at the $5 level, earning an online thank you, and 23 gave at various levels over $80 for additional rewards). Boyle explains his decision to use Kickstarter this way: “We found that our online sales for Surrogate Valentine were very strong when we sold the DVDs through PayPal, but that the numbers plummeted when we switched to Amazon Fulfillment. I don’t know what that means; perhaps the audience has a stronger response to handmade, organic distribution strategies. We decided to use Kickstarter as the exclusive online distribution platform for Daylight Savings in order to keep our budding audience engaged in what we are doing next. By allowing people to either get the movie as a Kickstarter reward for our future projects, or to purchase it at one of our in-theater events, we hoped to encourage people to be involved both on a virtual and ‘live’ level.”

Of course a lot of films on Kickstarter offer DVDs as rewards. It’s less common to make Kickstarter the primary platform for online sales. For Boyle, though, the decision speaks to the changing consumer mentality around physical media. “People do buy physical media if they’re buying it from you,” he says. DVDs are also sold at one-night-only live events where the films are screened and Nakamura plays. “If you are selling something in a theater, it’s all about an impulse buy,” Boyle says. “If they like the movie, they’re not just buying a DVD but as a physical memento of what was hopefully a memorable event for them. It’s less a movie franchise and more an experimental experience.

Daylight Savings is touring now, showing most recently at the Lighthouse International Film Festival in New Jersey. While merchandise sales, including a vinyl soundtrack, still generate much of the revenue at these events, the team is even rethinking the way they’re handling these sales too. “While selling merch at film festivals is a good idea in theory,” Boyle says, “there is a lot of awkwardness attached to that kind of transaction, and [we] are not natural salesmen. You start feeling like a guy selling fake watches out of a trench coat. We adjusted our strategy for Daylight Savings and allowed people to ‘pay what you want’ into a donation box. So far it’s worked pretty well.”

It seems that Boyle has met all his goals for Daylight Savings. He’s continued to expand his fan base beyond Asian Americans to music and other indie film fans, and he has two new Japanese-language films in the works—a further expansion of his craft. But the final word about this film’s revenue won’t come for a long time. But, really, that’s no different than it would have been had he taken a more traditional path. Boyle says he doesn’t even know exactly how Surrogate Valentine did on VOD in 2011. “I wish there were an equivalent to Rentrak for VOD,” he says.

One reason independent film is so engaging is that its films are so diverse. It stands to reason, then, that each film’s distribution path should reflect this individuality. As we’ve already seen with films like these, evolving technologies will just open more doors as enterprising DIY-ers find new and exciting ways to get their films out there and accomplish their goals as independent filmmakers.