Back to selection

Back to selection

Shutter Angles

Conversations with DPs, directors and below-the-line crew by Matt Mulcahey

Managing Anamorphics in 16:9 and the HBO Learning Curve: DP Rachel Morrison on Confirmation

Confirmation

Confirmation During our talk about her work on HBO’s Confirmation, cinematographer Rachel Morrison lamented that “as a DP you wish you had total freedom to tell whatever story you want to tell, however you want to tell it.” Of course, that’s not the reality of production. Parameters are always imposed – whether they are budgetary restrictions or technological specifications.

Morrison talked to Filmmaker about working within her given parameters – including a 16:9 aspect ratio, losing the hero location shortly before production, and dealing with the garish decor of the early 1990s – to craft HBO’s reconstruction of the acrimonious Clarence Thomas Supreme Court confirmation hearings.

Filmmaker: Walk me through the type of research you do for a story like this where there’s so much archival material available. We’re roughly the same age and I clearly remember watching Anita Hill’s testimony on television.

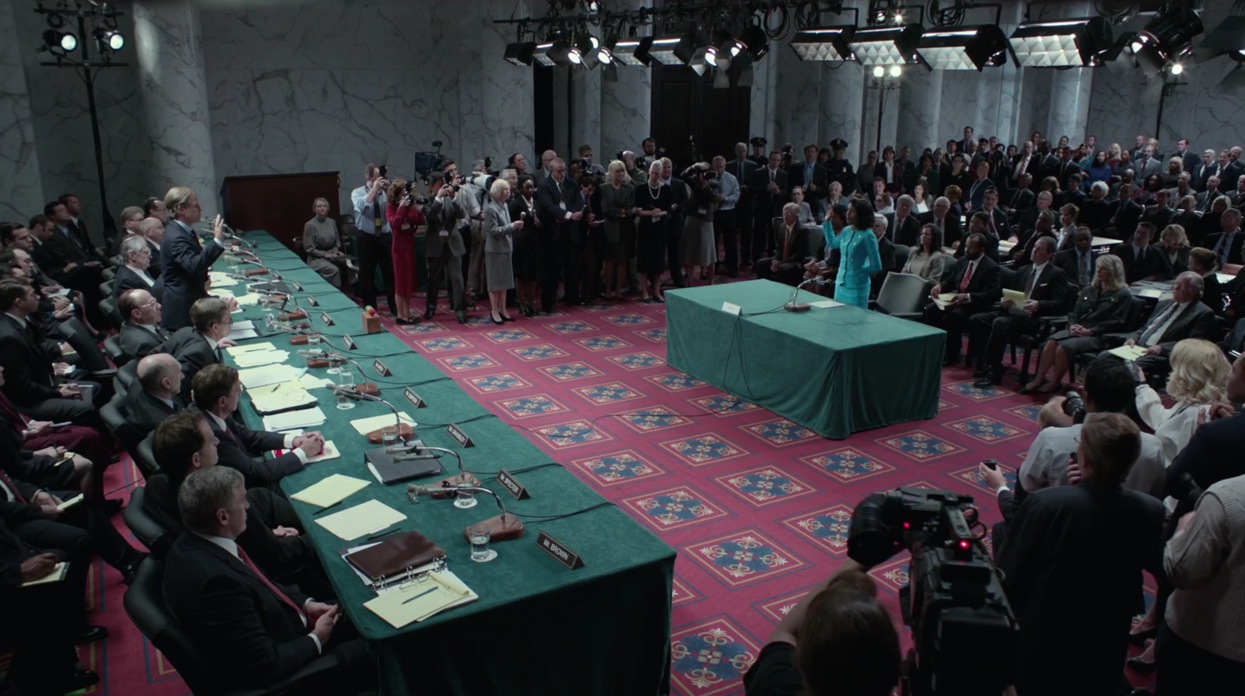

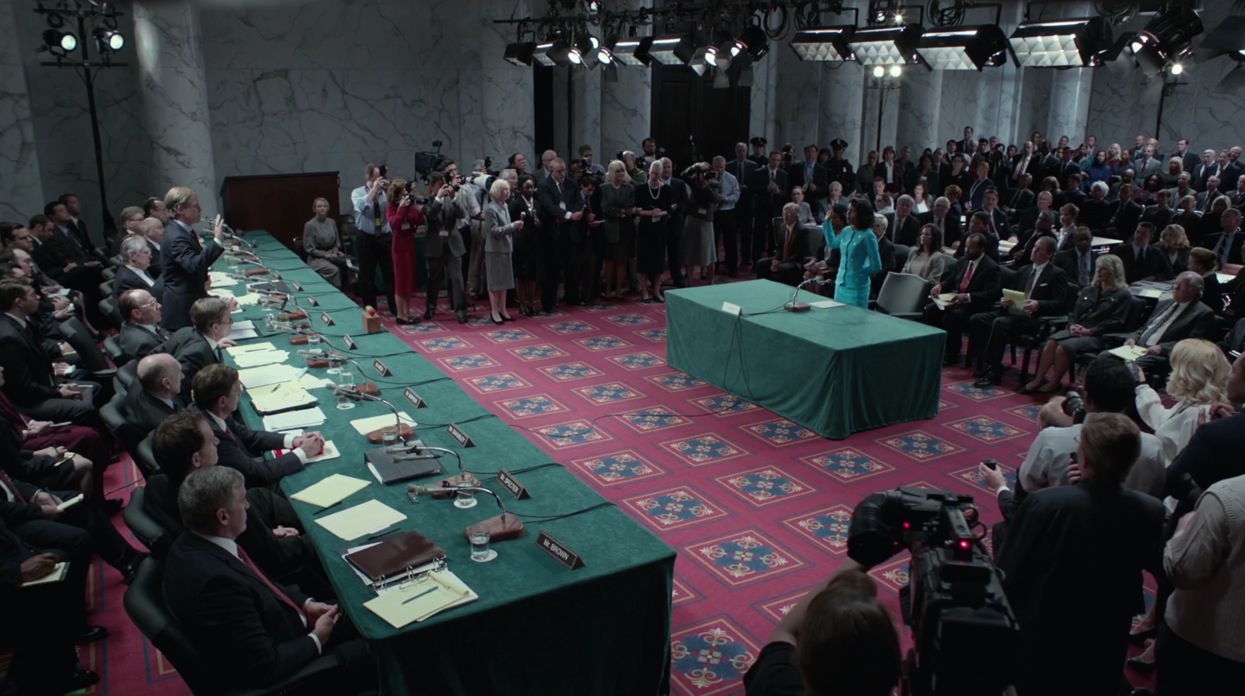

Morrison: I wish I could say I remember it as clearly — I have the worst memory in the world — but I remember my parents unusually glued to the TV and deeply engaged in conversation about the hearings and I had some sense of what was transpiring but didn’t fully comprehend it. So, I did end up watching a good amount of archival material, both to reimagine it visually but also to understand from an adult perspective what it all meant. Anything that’s historical, I think you start with talking about the ways that you want to be true to the authenticity of what happened and then the ways that you feel like you need to depart from it. The caucus room [where the hearings were held] was an essential location with a very specific look, but those tables [where Hill and Thomas sat to give testimony] were such a vibrant green and the rug was so red, both of which were a DP’s worst nightmare. So we made a conscious decision to alter the colors slightly so that they wouldn’t be distracting.

The same was true of the wardrobe. Those ties were so ridiculous. [laughs] The ’80s and ’90s have this almost caricature aspect now that works great in a comedy, but in a drama we don’t want people to be looking at hair and ties and outfits. We want them to be looking at faces and listening to words.

Filmmaker: Some of the details of the hearings, such as the color of Anita Hill’s dress, are so iconic that you’re, in a way, married to a certain color palette.

Morrison: Thankfully there’s something very cinematic about that color. I’m glad that dress wasn’t fluorescent orange because with something that iconic you can’t really depart from it.

Filmmaker: You’re working again here with Dope director Rick Famuyiwa – but with a drastically different style. What were some of the conversations the two of you had in preproduction in terms of establishing the visual language of Confirmation — how the camera would move, how you would frame things?

Morrison: Unlike Dope, where the whole movie is almost a giant chase, the challenge with Confirmation was how to make it visually interesting and dynamic when most of the characters are sitting in one place. Handheld obviously didn’t feel right for most of it and big camera moves would be unwarranted. It was ironic because I finally had the time and money to do huge, sweeping Technocrane shots, but they just weren’t motivated. Can you imagine how wrong it would have felt to sweep in and out on Clarence and Anita as they are giving their impassioned testimony? There were times to do very specific dolly moves around them and pushes in on certain moments, but we didn’t want to overuse the “dolly in” because that can feel almost like it’s doing the work for the audience. We were conscious of not having these “dun dun dun” moments and spelling things out.

We really wanted to embrace the idea of spectacle. More than anything what unified both Anita and Clarence is that they were put in the spotlight in front of a judge and jury of white older men. We referenced it almost to a boxing match or a wrestling match where we wanted to embrace the lights that were a part of that caucus room. If you look back at photos, you see that grid of lights overhead. You can feel the weight of all of America watching them, like they were front and center on a stage. Then we talked about ways to differentiate the look for Anita and Clarence from the judge and jury and we ended up shooting with spherical lenses for everybody else’s storyline, but once Anita and Clarence are under the microscope we shot their narratives with anamorphic lenses.

Filmmaker: I subscribe to HBO Now and some of the non-original content is cropped to a 16:9 aspect ratio and some of it is presented in its original aspect ratio. Confirmation is 16:9. Was that a choice you made or was it dictated?

Morrison: When you originate content for HBO, it has to be 16:9. So this was never going to live in a 2.39 world. The spherical lenses are native 16:9, roughly, but the anamorphic lenses are native 2.39 so we had to crop into the middle [of that 2.39 image]. Doing that creates this weird effect that is almost the opposite of a scope [aspect ratio]. I found it to be very claustrophobic, which was something else we were going for – this idea of being closed in and there being no escape.

Filmmaker: How does your approach change when working on something intended for television or even smaller devices? Does it change the way you frame or even change the way you color grade in the Digital Intermediate? I imagine televisions and handheld device screens have significantly less dynamic range than theatrical projection.

Morrison: This is the first time I shot something that was never intended to live on a movie screen, which was a new experience for me. And yeah, it does change things. This was actually the first time that we ever did the DI on an LCD screen as opposed to a projection screen and, yes, there is less dynamic range and the blacks tend to be blacker. Also, unfortunately, television settings are so unpredictable. Half the people have their TV set for sports mode and motion blur and are probably watching it in horrible soap opera mode. But those are things you can’t really account for.

As far as the frame goes, often time people’s TVs are zoomed in. But I wasn’t that conscious of the edges of the frame. I feel like you have to compose for what the best version is. You have to imagine it’s being seen the way you would set your TV up. For instance, the idea of mixing anamorphic and spherical, where you’re cropping into the anamorphic, it actually softens the [anamorphic] image quite a bit. Had the movie been for theatrical, I probably wouldn’t have done that because you would notice the difference. I never thought I would see [Confirmation] theatrically, but at the premiere I actually did see it on a huge screen and sure enough you could see a little bit of the difference [between the spherical and anamorphic shots]. But when you’re watching it on a 51-inch television, you can get away with it. You’d never notice.

Filmmaker: Netflix now has a 4K mandate for its original programming — which makes the Alexa less of an option. Did you have to deal with any similar restrictions?

Morrison: HBO doesn’t have a 4K mandate, thankfully. The Red is such specific look and I don’t like it as much as the Alexa. However, because I was cropping into the anamorphic frame, [HBO] was concerned that the vertical resolution wasn’t going to live up to their specs because it actually did come in a little bit under their mandate. They did a test through quality control and it was such a subtle difference that they approved it. There’s always technical specifications — whether it’s a 4K or a 16:9 mandate — but as a DP you wish you had total freedom to tell whatever story you want to tell, however you want to tell it.

Filmmaker: Did you end up shooting Alexa?

Morrison: Yes, we shot Alexa XT and we mixed ArriRaw with ProRes. Some of that was budgetary — we probably would’ve shot the whole thing Raw if we could have afforded to — but we shot all of our VFX and comp work Raw and everything else was ProRes.

Filmmaker: Did you shoot the whole movie in Atlanta?

Morrison: Yeah we did.

Filmmaker: What location did you use to stand in for the Senate Caucus Room?

Morrison: Funny you should ask that. A large part of the decision to shoot in Atlanta was that the Georgia State Capitol interior was a very good match for the Capital Building. Then, mere days before we started shooting, after we tech-scouted that location, we got word that we couldn’t shoot there. Nobody ever really told us why, but it was probably because Clarence Thomas is from Georgia and somebody finally put two and two together. So we lost our biggest location right before we were supposed to begin shooting. That was devastating for me, quite frankly, because that location was so much of our production value. When you have a film that’s set largely in offices and corridors and courtrooms, it is a huge breath of fresh air to be able to open up to this beautiful Georgia State Capitol, which has this incredible dome and natural light and has a real grandeur to it. Losing that was really hard for a lot of us. The solution was to do a lot more with greenscreen. Some of our exteriors are actually all comps. We shot on steps with greenscreen and then comped the actual steps to the judiciary building and the same thing for the Supreme Court itself. Even if we had been able to shoot in D.C. for financial reasons, it would’ve been for naught because everything is under construction right now. We wouldn’t have been able to get any of our exteriors there anyway.

Filmmaker: Since we’re talking right in the midst of this year’s NAB, did you use any new lighting technology for the first time on Confirmation? It seems like LEDs are evolving as quickly as cameras.

Morrison: Every shoot I do there’s new LED technology. Ultimately they’re all designed to be DMX dimmable and to be soft. I think we probably had some [Arri] SkyPanels, which are becoming more and more prevalent.

We made some of our [camera] flashes out of LEDs too. The one thing about actual camera flashes is that you get a rolling shutter effect if you’re shooting with a 180-degree shutter — you might recognize it as that kind of half-horizontal frame. So when the camera was still and the subject was still, we could [avoid that effect] by forcing a 270-degree or 360-degree shutter, but when there was movement you couldn’t do that. So then we’d use panel flashes, which are amazing but very expensive, or gaffer Larry Sushinski created our own flash panels out of LEDs that had a burst mode.

Filmmaker: Let’s walk through a few shots, starting with your technique for replicating ’90s-era cameras for Confirmation’s faux-TV news footage

Morrison: We actually shot standard def. That was something that I felt strongly about and Rick supported me. So often people just shoot it on the Alexa and fix it in post, but I don’t think that the post analog look ever really works. I feel like I can always tell. At first I thought we’d shoot 720p, but even that was too sharp so we ended up shooting standard def 480p. We came to that through a lot of testing with old cameras. We ended up using the Panasonic AJ-HPX3000. It was literally the only option that could shoot standard def and record to cards rather than tape. So the analog standard def look was because it was shot with a standard def camera.

Filmmaker: For the scenes in the Senate Caucus Room, is the space lit by the practical units we see in the frame?

Morrison: Largely. Certainly in the wide shots it is. Everything is on a dimmer board so when we went into the close-up work we’d probably turn off 80 percent of what you see in this wide shot and bring in supplementary sources.

Filmmaker: What are some of those units we see. Are those Source Fours up on the left?

Morrison: Yep, Source Fours on the left. Then Zip lights with grids are those bigger lights that you see. And then Babies and 2K’s — all things that existed in 1991.

Filmmaker: This shot plays into what we talked about before – about how the color of a costume can influence your job. This shot doesn’t have the same feel if Hill (played by Kerry Washington) is in a fluorescent orange dress. Was this location something you found after the Georgia State Capitol fell through?

Morrison: It was in the Archives building in Atlanta, which is where we shot several other locations. As soon as I saw this location, I was like “We’re shooting as much as you’ll let me here.” Actually this scene was written out of the shooting draft of the script and I just kept saying to Rick, “We have to find a way to write it back in.” So he put pressure on the line producer and the assistant director to make time for it. And we ended up liking it so much that we moved a full dialogue scene to that location with [Washington] and Jeffrey Wright.

Filmmaker: Did you swap out the bulbs in the overhead fixtures?

Morrison: We did swap them, if for no other reason than because they didn’t match each other. In this day and age you don’t necessarily need to switch them for daylight or tungsten balanced bulbs because digital cameras can be color balanced so easily to accommodate that source, but in a lot of these industrial spaces they’ll throw whatever bulbs they can in the fixtures. In this case we just made them all match.

Filmmaker: How about this anamorphic shot? You can still see the edges of the frame start to bend even with that center crop you talked about.

Morrison: This is the subtle way I was hoping to use anamorphic as a motif specifically for Anita and Clarence to make their world feel a little bit surreal. The focus of this shot takes you toward the middle of the frame, but [Anita] is on the bottom right and she’s intentionally minimized in the frame, a repeating metaphor, and there’s something off about it because her life for those three days — and quite frankly for the ten years that followed and, really, forever – would never be the same again. I could only imagine what that must feel like — like your lines don’t feel straight anymore.