Back to selection

Back to selection

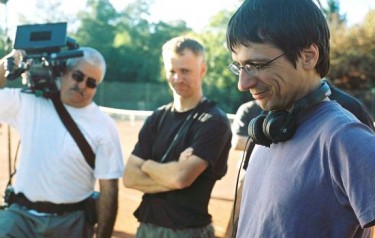

“MONSIEUR LAZHAR” WRITER/DIRECTOR PHILIPPE FALARDEAU

With its intensely concentrated industry buzz and high profile bidding wars, Sundance is one of the few places where filmmakers’ careers can be transformed overnight. But writer/director Philippe Falardeau says he’s not looking for a Cinderella moment when his French-language feature Monsieur Lazhar screens out of competition in Park City this week as part of the fest’s Spotlight program. The film — about a mild but mysterious Algerian immigrant to Montreal, Canada, (Mohamed Falleg) hired to replace a school teacher who has committed suicide — has already picked U.S. distribution through Music Box Films, a slot as Canada’s official submission for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar and a handful of festival honors, including the Audience Award at the Locarno Film Festival and Best Canadian Feature honors at the Toronto International Film Festival. Besides, Falardeau says he’s already had his big, transformative moment, and it came long before the success of his first three features, Congorama (2006) and It’s Not Me, I Swear! (2008).

Filmmaker: Sundance is one of the few places where a filmmaker’s career can truly be Cinderella-d, so to speak. Are you so jaded that you don’t think about that sort of thing?

Filmmaker: Sundance is one of the few places where a filmmaker’s career can truly be Cinderella-d, so to speak. Are you so jaded that you don’t think about that sort of thing?

Falardeau: I do care. I do get excited. I would be lying if I said I didn’t. But, first of all, I’m realistic. I studied political science and international relations, and it was a series of accidents that made me direct a documentary and then I migrated to fiction. And sometimes I have to pinch myself, because I wake up in the morning and say, “Wow, I do this incredible job and make a living out of it.” And I’m one of the few people in Quebec who can make a decent living out of making films. I write my own stuff and I make a film every three years. I write my own stuff and I make the films, so it’s one every three years. So in a way the Cinderella story already happened to me. If a second one happens, I’m going to be super happy, but it already did happen to me.

Filmmaker: You were on a reality show?

Falardeau: In 1992, I participated in this program called The Race Around the World (La course destination monde) on the French Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Every year, they chose eight young amateur contestants and they traveled alone around the world with S-VHS cameras. We had to do 20 movies in 26 weeks, and it was a race. We’d arrive in each country and make a movie in one week. At that time, they didn’t have any software on computers to edit your own film, so we had to edit the thing on paper and send the rushes and the editing plan via FedEx and move on to the next country, and the films were shown three or four weeks later on television while we were still going around the globe, and we were [evaluated] by judges and it was a contest. It was kind of a reality show in which you really had to do something creative and intelligent and you had to take care of your own self in different, difficult countries. I went to Sudan, to Libya. And when I came back, that’s when my opportunities started as a filmmaker, so it changed my life.

Filmmaker: How did you get involved in that program?

Falardeau: It had been on for three or four years, and I applied like you buy a lottery ticket: You dream of winning a million dollars, but you know you’re not going to win it. I was really shocked when they decided to choose me. There were different steps — an interview, we had tryouts. Finally, they said, “Okay, you’re leaving for six months and you go wherever you want to go on the globe. You’re going to be alone and you have to make 20 films.” I was really scared and I thought, what the hell did I do? They’re going to find out that I can’t make films. So I learned my craft on my own, making short films. At the beginning, the films were terrible, but as the weeks progressed, I kind of progressed myself.

Filmmaker: Were you reading time code on the video then sending it back for them to cut?

Falardeau: It was a prehistoric time. There was no time code on the camera, no little screens, so I had to watch my little rushes inside the eyepiece and I had chronometer and I had to time all my shots, then do an editing plan and tell the editor, okay, you’re going to take that shot from that cassette and this narration bit and the music I left you back in Montreal. So it was a puzzle to make in your head and I saw my films when I came back six months after.

Filmmaker: Did any of your competitors on the show come back and make a career of filmmaking?

Falardeau: Most of them did. Denis Villeneuve (Incendies) is a product of that same television show two years before me. A lot of us became documentary filmmakers; some of us are fiction filmmakers and a lot of people are working on television, so it became kind of this cool thing. It was on from 1988 until 1999, when it was taken off the air and replaced by all kinds of stupid reality shows, where you just pack some young people in a room and wait for shit to happen. And I thought it was a wrong turn.

Filmmaker: Like the typical documentary, Monsieur Lazhar explores some hot button social issues.

Falardeau: When I first decided to make that film, I was not thinking about social issues, although I knew there was going to be a bunch of them in the film. I know for sure that people don’t go see films to go see subjects or ideas. They want to follow characters. So my first goal was to have interesting characters. This guy was an immigrant and he tells the truth to the immigration officer and he lies at the school to get the job. Now, there are some of the issues in the film. For instance, can you touch a child, embrace him? Can you give him a pat on the back to encourage him? This has become something very taboo back home, and probably also across North America. In a certain sense, it is ambiguous and a little bit politically incorrect. I thought I was going to get attacked when it came out in my own province in Quebec [in the fall], but, to my surprise, the teachers who are working at the school are quite happy that I’ve tackled that issue. But back to the first question, I don’t think I would make a film solely based on the desire to tackle and socially engage a subject.

Filmmaker: As you promote the film in different countries, are you finding that these teaching issues are universal?

Falardeau: Yes. Not only the teaching issues, but also the fact that we’ve all been to elementary school. We all have our intimate point of entry into that story, and I realized that after a couple of screening and festivals that the film would appeal to other audiences, because no matter where you go in the world, everyone has gone to elementary school, to primary school. And I think that’s why people are touched by the story — because they can identify themselves with kids.