Back to selection

Back to selection

Religious Fervor and Precarious Times: The 2016 Indie Memphis Film Festival

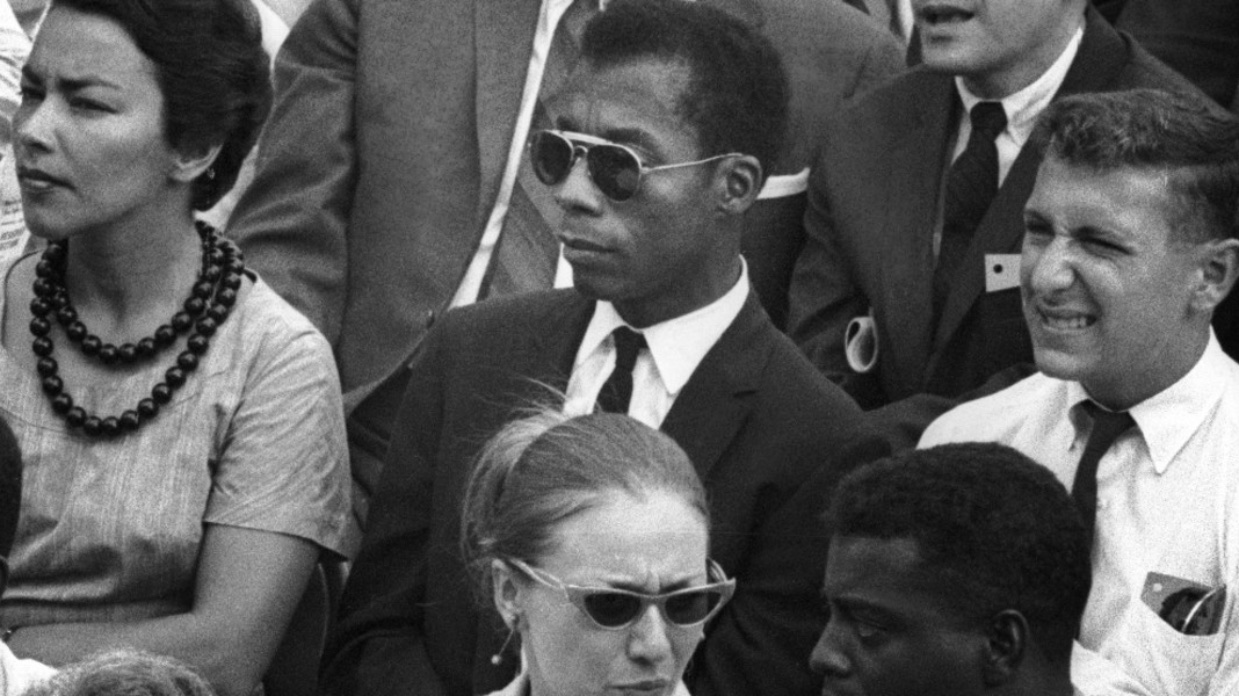

I Am Not Your Negro

I Am Not Your Negro I arrived in Memphis a week ago, but it feels like longer. It was a balmy evening like the last breath of summer, and I hadn’t yet met the full realization that Trump could become the President-elect in a matter of days. Making my way back from the opening night screening of The Invaders, a Memphis-produced documentary chronicling the local militant group’s role in the 1968 sanitation workers’ strike and their meeting with Martin Luther King, Jr. right before his assassination, I walked the empty blocks with a homeless vet and long-ago college football star who foreboded the results of the coming election with biblical gravitas. “In the last days, perilous times will come,” he quoted scripture before adding, “and look around you, these are perilous times.”

Both this stranger’s diagnosis of the precarious state of our nation and his religious fervor accented themes in the program of films I watched over the next week — documentaries like Raoul Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro, centered around James Baldwin’s writings that interrogate the racial imagination, and Maisie Crow’s Jackson, on the fight to keep open Mississippi’s only abortion clinic, and narrative features like Jake Mahaffy’s Free in Deed, a drama about a family turning to the church after the system fails them, and Celia Rowlson-Hall’s Ma, an experimental dance film revising the story of Mother Mary’s pilgrimage. (I should mention that I was attending the festival both as a journalist and a filmmaker, with a short documentary film on the Christian tradition of gospel miming, which screened with Ma.)

The threads of resistance and religion woven into the program together suggested intersecting strategies for survival in the face of exasperating circumstances. There was a satisfying lack of catharsis offered in many of the films, and the way art can mirror life’s frustrating narratives was underscored in post-screening discussions. Following The Invaders, surviving members of the activist group were quick to note ways that systemic racism in Memphis persists today while, in his film’s Q&A, director David Shapiro noted his formal decisions to avoid cliched cathartic conclusions in his documentary Missing People, chronicling twin stories of a New Orleans artist and a New York gallerist linked by trauma. On screen at Indie Memphis, just like in reality, simple happy endings were hard to come by.

On a more uplifting note, the festival was successful in highlighting diversity on screen and behind the camera. Women filmmakers dominated the awards with prizes for best documentary, best narrative feature, and excellence in filmmaking, respectively going to Crow’s Jackson, Deb Shoval’s AWOL, and Rowlson-Hall’s Ma. Queer filmmakers and subject matter were represented by several Memphis-based projects including a 20th-anniversary screening of Ira Sach’s first feature film The Delta, Madsen Minax’s Kairos Dirt and the Errant Vacuum, which picked up the award for best local feature, and Flo Gibbs’s documentary Mentality: Girls Like Us. Musa Syeed’s film A Stray was a project especially concerned with representation. Aiming to expand the audience’s idea of Muslim-Americans — i.e. they aren’t all Arabic — the Kashmiri-American director set his coming-of-age drama in Minneapolis’s Somali refugee community. And during the festival, Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro and Rita Coburn Whack and Bob Hercules’s Maya Angelou: And Still I Rise, both documentaries made by and about Black artists, were sold out, with spillover audience members sitting in the aisles and standing in the back for the encore screening of I Am Not Your Negro that I attended.

Still, several films in the program followed the familiar formula of featuring Black actors and documentary subjects but being authored by white directors, including Free in Deed, The Invaders, Gip, and I Am the Blues, two of the local shorts funded by last years’ IndieGrants: Broke Dick Dog and Dirty Money, and my short Gospel Mime. It’s a dynamic I was provoked to consider more when, during the post-screening discussion, a white producer called Free in Deed the “first film of color” to win at the Venice Film Festival. Films are obviously collaborations, but is having a Black cast enough to qualify a project as a “film of color?” Thinking back to recent festival darlings like Tangerine (2015) with Black trans leads and a straight white cis male director, it’s hard to criticize directors giving opportunities to these performers but something is amiss when representation is lopsided, happening more on camera than off. At IndieMemphis, the inclusion of a repertory film series, The Pioneers of African-American Cinema, complicated simplistic narratives of linear progress, which are implied in calling Free in Deed any sort of “first.” The series included two silent films, The Symbol of the Unconquered (1920) and Body and Soul (1925), by legendary director and independent producer Oscar Micheaux, who made over 44 films between 1919 and 1948.

In many ways, Memphis encompasses the racial divisions cracking open this nation right now. It’s a blue city in a red state. Its streets house both a memorial to King outside the Lorraine Motel, where he was shot, as well as a statue of Confederate General Nathan Bedford Forrest, the first Grand Wizard of the Klu Klux Klan. Built on the Mississippi River, the city has always been a hub. Once a center for the cotton trade, now Nike and FedEx both base their operations here. Maybe it’s a site for racial histories too, because ideology needs the same sort of channels to circulate. Regardless, it seemed a fitting place to present a program of films that quietly considered both the past and the future of a nation built on slavery and systemic dehumanization, where every step of racial progress has historically been met by bigoted backlash.

Moving beyond just offering diversity and representation, the program at IndieMemphis considered these questions programming multiple films that rightfully centered white people, examining their role in upholding white supremacy in America, and the circumstances and psychologies that let them feel good about what they’re doing. Through an intersectional feminist lens, Jackson, for instance, showed how poor Black women in Mississippi are disproportionately devastated by lack of access to sex education, birth control, and abortions. One of the main characters in the film is a do-gooder white Christian woman named Barbara who runs a pro-life Pregnancy Crisis Center in Jackson. The film includes a vital meditation on how Barbara is able to feel good about her role saving unborn babies while killing opportunities for poor Black women.

Good White People, while it could be describing Barbara, is a short documentary about gentrification in Cincinnati’s Over-the-Rhine neighborhood. Directed by Jarrod Welling-Cann and Erick Stoll, the film — which won best short documentary — follows a Black working class family who have to relocate their home and two businesses. Through its title as well as its camerawork, which lingers on white people on walking tours in the historic neighborhood and drinking beers at their newly renovated brew pubs, the film centers these newcomers’ complicity and willful lack of self-awareness.

Peck’s I Am Not Your Negro perhaps centers white Americans most of all. The essay film, which juxtaposes archival footage with 30 pages of a text Baldwin was working on when he died, performed by Samuel L. Jackson, updates the penetrating essayist’s concerns to our contemporary era. The film finishes with Baldwin directly addressing white people: “If I’m not a nigger here and you invented him, you, the white people, invented him, then you’ve got to find out why. And the future of the country depends on that. Whether or not it’s able to ask that question.” This self-reflection Baldwin urges seems as crucial now as ever before.