Back to selection

Back to selection

Focal Point

In-depth interviews with directors and cinematographers by Jim Hemphill

“I Had a 40-Year Career That Was Mostly Just Riven with Existential Panic”: Two and a Half Men Co-Creator Lee Aronsohn on his Debut Doc, 40 Years in the Making: The Magic Music Movie

The Magic Music Movie

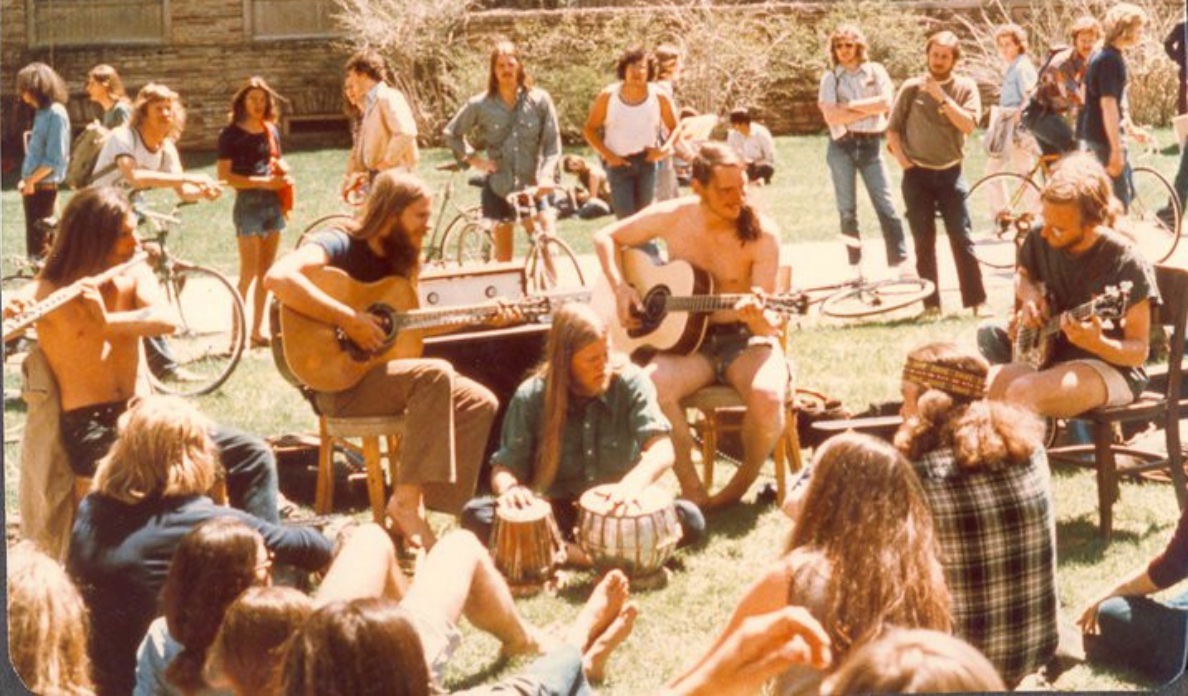

The Magic Music Movie Lee Aronsohn was a college student in the early 1970s when he discovered Magic Music, an acoustic band based in Boulder, Colorado that attracted a devoted following thanks to their beautiful harmonies, memorable lyrics and bohemian lifestyle. In spite of flirtations with a number of record labels, the group never took off — they never even released an album — and by 1975 they broke up. Forty years later, Aronsohn — now one of the most successful writer-producers in the history of sitcoms thanks to his work on Murphy Brown, The Big Bang Theory and Two and a Half Men, which he co-created — got curious about what ever happened to the band and began researching them. The result is 40 Years in the Making: The Magic Music Movie, a documentary in which Aronsohn interviews the surviving members of the band (as well as various wives, exes and business partners) before reuniting the group for a successful reunion concert. The insights and observations that grow out of Aronsohn’s interviews are as varied as they are affecting, as the film becomes a meditation on the complicated factors that determine artistic success or failure and how they intersect; the interplay between talent, personal relationships and life-changing circumstances both uncontrollable and self-inflicted is fascinating and poignant, and the questions the movie asks about what constitutes success and fulfillment in an America that has changed so much since Magic Music’s birth are profound and resonant. In an astonishingly compact 99 minutes, Aronsohn creates an elegantly balanced ensemble character study, a rousing musical film, an inquiry into moral, political, and social values, and so much more — it’s a movie that was worth the 40-year wait. I sat down with Aronsohn in Los Angeles a few days before the film’s theatrical release (it’s currently playing in New York and will be rolling out across the country before a September 4 digital release) to talk about earning his subjects’ trust, finding the story in 100 hours of footage, and how a background in TV comedy helped him direct his first documentary.

Filmmaker: This movie ends up being about so many things — friendship, aging, regrets, the intersection between art and commerce, how America has changed since the early ’70s — and I’m curious what your starting point was. Did you plan to explore all those issues, or did they just grow organically out of the process?

Lee Aronsohn: When I first told my friends about the idea, I said that ideally I wanted to come up with a film that said something not only about the journey of the band from there to here, but the journey of our generation from there to here — and the journey of Boulder, because everything has transformed so much in the last 40 years. I started off thinking that there was no way I’d be able to stuff all of that into a 90-minute movie, but I would say a good 85 to 90 percent of what I wanted to be in the movie is there, so I’m happy about that. It started with my view of Magic Music as a fan, which was a very romantic image. I just thought, “here are these incredibly cool hippies that live in school buses and smoke dope and get all the girls and are living the dream.” Of course, I found out what the reality was, which is that they were real people with the same struggles that everybody else has. And what was fascinating to me was seeing how they looked at the decisions they’d made. Because I basically “sold out.” I came out here interested in performing, but I ended up being a sitcom writer because that’s what people would pay me to do. It wasn’t a passion of mine or a goal, but it became my career because people kept paying me to do it. And so, like a lot of people, I’ve asked myself, “Did I take the right path?” I wanted to know how the guys in the band would answer that question too. And they answer it in different ways.

Filmmaker: Were you working on a TV show when you embarked on this documentary?

Aronsohn: No, I’d retired from television. I came back for the final episode of Two and a Half Men after being off the show for a couple years. Chuck Lorre and I, and the other guys, wrote and produced a one-hour finale. It was fun, but I realized during those two weeks of production that I never needed to do it again. I’ve done it. And so, the question was, what was I going to do instead? I didn’t want to do any more sitcoms, I was very clear on that. And I don’t know that I’m a drama writer. So I wanted to catch my breath and take it easy for a while and hope that something would occur to me. I was asked to speak at a film symposium in New Zealand and was down there with a friend of mine, Fleur Saville, who had produced a marvelous film called Blood Punch that I saw at the Austin Film festival a few years ago — that’s where I met her. I had been in touch with Chris Daniels [Magic Music’s lead guitarist] for a little over the year because I had found him online by Googling “Magic Music Boulder” after years of just Googling “Magic Music” and coming up with singing magicians. I finally got a line on Chris, because he’s still in the business — he’s the only one that really is. He told me about this album that a few of them had done with some studio musicians, and the story of that is in the film. I was very anxious to hear it, so I would email him every few months and say, “How’s the album coming? When’s it coming out?” Every time I emailed him, it was always, “It’s going to be out in six months.”

So I’m in New Zealand and I’m telling Fleur about the band. I don’t even know how it came up, but I went to Google them and Chris had posted a YouTube video for the song “Colorado Rockies,” which is a long, eight-minute song. And he had just put together this collage of his entire photo collection of the old days of Magic Music and some of the guys who had gotten together over the years and more present-day stuff. And I looked at this photo collage, along with the song, and I said, “Wow, that’s such a journey. There’s got to be a story there, and it’s not a story anybody else is going to tell because nobody else has heard of these people.” I said to Fleur, “You know what? I’d like to make a documentary on these guys. And I’ll probably never do it.” But when I got back to the States, the idea just kept growing and growing in my mind. It seemed like this was something I was uniquely suited to do, and I was lucky enough to have the opportunity and the means to do it. So I decided to do it and asked Fleur, “Would you want to do this with me? Would you want to produce?” She has what I lack, which is organizational skills, so she made it happen, really. Her husband Dean Cornish, a marvelous cinematographer and director in his own right, became my director of photography and I trusted him when it came to cameras and stuff like that. We just went out and did it. We filmed in five different phases over a year and a half. And then there was the long slog of trying to edit something out of 100 hours of footage.

Filmmaker: What was the reaction of the guys in the band when you approached them about doing this?

Aronsohn: When I first approached them I just wrote to Chris, who I was already in an email correspondence with. I said, “How would you feel about having a documentary made about Magic Music?” No response. I suddenly realized he didn’t know me from Adam. All he knew was I’m just some guy who said, “Hey, I used to hear you in Boulder years ago.” So I wrote back to him after a few days and said, “You know, it occurs to me I’ve given you no reason at all to take me seriously.” I sent him a link to my IMDb page, just to show him that it was a legitimate inquiry. Then I got a response, but these guys, as you can see in the movie, are not really trusting of establishment entertainment figures. So there was a feeling-out period, and I had to earn their trust. Chris and Tode and Will were coming to L.A. to rehearse, because their plan had been to tour in support of this album they were putting out. Initially I thought that was going to be the documentary. I shot them rehearsing for two days at Robby Krieger’s studio and cut something together. I interviewed them and cut a four-minute piece out of the interviews with some of the music, because I found out that they had these old tracks they recorded in the ’70s that had never been released. The guys looked at it and they dug it, and that’s when I got the okay to plan a more elaborate shoot. But the album tour never happened — the album came out in the summer that we were shooting, but it didn’t really get any traction.

Filmmaker: When did the idea come to you to get the whole band back together for a reunion concert?

Aronsohn: It came to me when we were in Boulder the first time shooting, when I brought them back and had them play on campus. That was my big idea, to get them together to play on campus again the way I remembered them. During that campus shoot, I realized that I wanted to do something bigger and I wanted to do it with everybody that I could get. I showed Dean The Last Waltz as something to aspire to in terms of the look, and shot with seven cameras, one of which was handheld, just shooting the audience. I wanted a lot of protection, so I made sure we had one master, one camera up in the balcony that was shooting the whole stage, so that no matter what the other cameras were getting I could always cut away to that.

Filmmaker: You mentioned editing the movie down from over 100 of footage. What was that process like?

Aronsohn: I had somebody do an assembly after each phase of the shooting — after the interviews, after the El Dorado visit and playing on campus, and so on. But finding the structure of the movie was just trial and error, and it was brutal. I mean, I look at the first cut and it’s astounding to me. So much that I thought was going to be in the film isn’t, and it was a constant process of paring down, paring down, paring down, because the first cut was like three hours long. It was really intuitive. I remember having no idea what the Boulder episode was about until I came across dialogue about how these people are like family. Then I realized that was what the whole Boulder thing was about — about family, about the connections that they still have. Once I had that insight, editing it became relatively easy. But I didn’t go in with a plan.

Filmmaker: Did you feel like any of the things you learned over 30 or 40 years of doing sitcoms applied to what you were doing here?

Aronsohn: Absolutely. The editing is remarkably important in comedy, far more important than in any other form — a couple of frames either way can kill a joke. I’ve developed kind of an internal pacing metronome, and I’ve learned story structure and setting up and paying off things. There are a few big laughs in this movie, and they work because I know how to make them work. I know how to set up very early on that there’s never going to be a drummer in Magic Music and then pay it off at the very end. Or going back to Will every time saying, “Eh, I should’ve signed that one. Yeah, it was probably a mistake. I should have put on shoes, yeah.” Every time we go back to Will, the audience laughs because of the way I structured it. I could’ve had different people saying the same things for each time, but by going back to Will every time, it becomes a running gag and it becomes part of the character created for the film. So that’s another thing that I learned by doing sitcoms.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting to me that you related to these guys, because from my perspective you accomplished exactly what they couldn’t. You figured out how to merge your creative impulses with the business side of things very successfully.

Aronsohn: It may look like that from the outside, but on the inside I had a 40-year career that was mostly just riven with existential panic. There’s always the feeling that somebody is going to come to my door, an official representative in show business will knock on my door and tell me it’s all been a mistake, give back the house, give back the money and go eat out of the better dumpsters in Beverly Hills. Because I never said to myself, “I want to be a writer.” The first time I had an opportunity to write, it was a guy named Ben Joelson who was a friend of my family’s and whose phone number I had when I came to LA for the first time in 1977. He was a TV writer, and he was very gracious. He was working on a new show called The Love Boat. And he took me to lunch and he came to see me do standup. And he said to me, “You know, you’re funny. Have you ever considered writing?” And my answer to him was, “Absolutely not. I hate writing. It’s like having a term paper due every day of your life.” Then he told me what they were paying writers on The Love Boat. And I said, “You know, I could give it a shot.” That’s how I became a TV writer. It was not thought out or anything like it. So I didn’t merge anything. It merged with me. And I did get a lot of satisfaction over the years doing it, but it wasn’t what I wanted to do. It wasn’t what I would’ve chosen to do. It wasn’t my passion. Because I never studied for it or prepared for it, I was always afraid of how long could I keep doing this before I’m found out?

Now, I’ve been asked to do another music documentary. And I think to myself, “Well, I don’t know.” This was like the perfect thing for me to do because I had a connection to it. I had the knowledge of it that nobody else had. And I knew that at the end of the day, no matter how lousy the movie was, I was going to have this beautiful music in it. So part of me just says, “You got really lucky with this one. Don’t press your luck.” But I do know I am good at certain things. I know how to tell a story. I think if I did another documentary, I would go in with more confidence because at least I know that at the end of the day I can find the story that’s buried in 100 hours of footage.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and Amazon Prime. His website is www.jimhemphillfilms.com.