Back to selection

Back to selection

Cannes 2022: Godland, Pacifiction

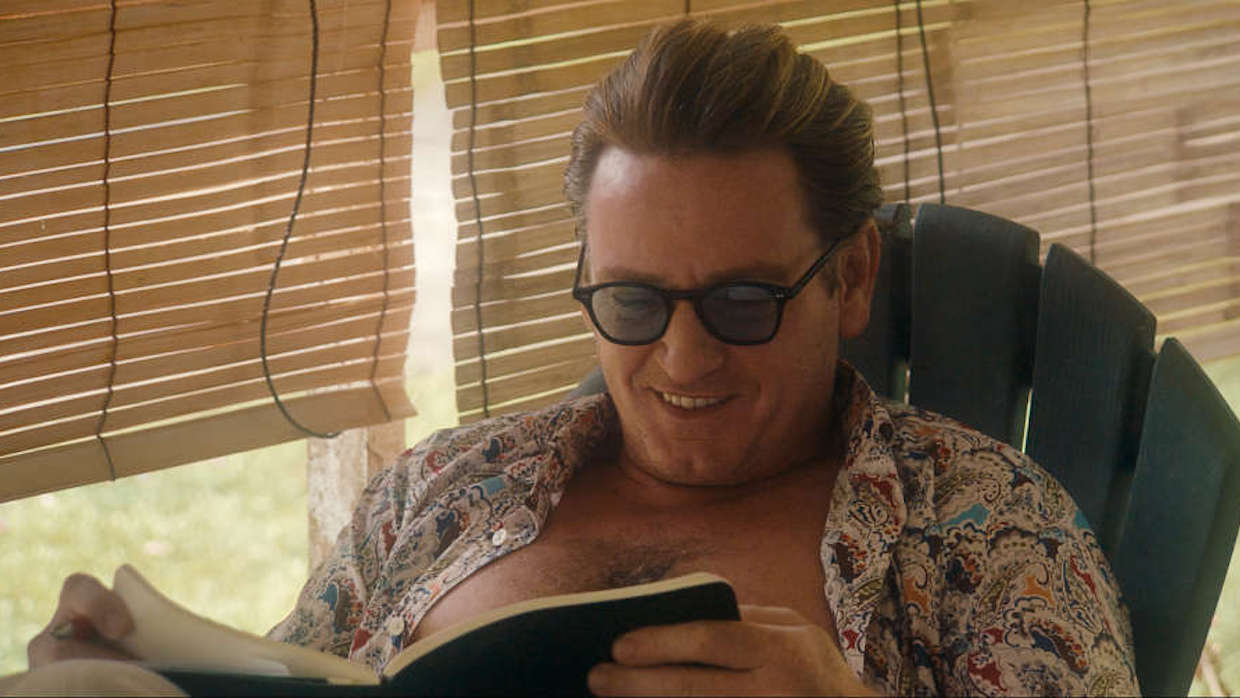

Benoît Magimel in Pacifiction

Benoît Magimel in Pacifiction Day 10 is winding down, and it’s become quite clear that, as was the case for the Berlinale last February, this year’s Cannes is a significant regression after a 2021 edition that overflowed with a pre-pandemic backlog. So many of the films I’ve seen, produced and completed (if not completely developed) in the midst of COVID-era constraints, have felt smaller, cheaper, cruder than what I’ve encountered here in editions past—not a judgment per se, of course, but a new, ill-fitted look from a festival that so pointedly touts its eventitude: the spectacle, the glamor, the scope of its pet auteur’s visions. Grandiosity, thus, has resided in the films’ durations. While it’s true that there aren’t any genuine butt-breakers in the festival (the longest, Marco Bellocchio’s six-hour Exterior Night, is technically a miniseries, and its screening was generously halved by an unadvertised 30-minute intermission), so many of the offerings in the Official Selection push well and unnecessarily beyond the two-hour mark. We’re getting more of lesser goods, and it’s made for a particularly fatiguing festival.

Hlynur Pálmason’s magnificently photographed Godland, the follow-up to his formally invigorating sophomore effort, A White, White Day (part of the Semaine de la Critique selection in 2019), is one of the few exceptions to this trend. The film is shot on 35mm and lets you know it by adopting what appears to have been an extremely hands-off clean-up after the digital scan was made, leaving copious specks and dust to decorate the image, itself encased by the rough and rounded edges of the film gate. Not near pastiche, the look suits the movie’s subject matter fairly well, inspired as it was by seven wet plate photographs taken by a Danish priest, which an early onscreen text informs us are the first to document Iceland’s southeastern coast. Thus, Pálmason’s narrative imagines the journey that produced these images, and follows the priest, Lucas (Elliott Crosset Hove), who in the opening scene is sent to Iceland by the Church of Denmark to establish a parish there.

The colonialist history of Denmark’s rule over Iceland, which drove the country through decades of economic turmoil and resultant poverty, hangs over the film. The title card is shown twice, first in Danish and then in Icelandic, and Lucas attempts to pick up some key words of the Icelandic language while sailing over, but grows immediately hostile towards their tongue after being told upwards of a dozen different words for “rain.” In truth, the inquiry into colonialism, while interesting, feels ornamental, and Pálmason’s interests are clearly more oriented toward image, landscape and tone, all of which he is palpably smitten with. He depicts these elements, especially his homeland’s glorious terrain, with a studied and austere awe, resulting in a film that compares favorably next to semi-recent landscape dramas like Kelly Reichardt’s Meek’s Cutoff (2010), Lisandro Alonso’s Jauja (2014) and especially Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007), not to mention masters of yore—Carl Th. Dreyer and John Ford, in particular—whose influence hangs over nearly every frame of Godland.

I make a point of listing these because, unlike Pálmason’s previous movie, Godland feels like it’s following a template. The conflict that develops between Lucas and his guide, Ragnar (Ingvar Sigurðsson, the lead of A White, White Day) feels disingenuous and divorced from the movie’s broader attitude—mythological brooding for its own sake—and seems to exist in order to manufacture showy scenes and shots that, again, seem to arise from other films. One example is a time-lapse motif that appears three times in Godland’s last act, an appropriation of the astounding opening scene from his own A White, White Day, in which a single landscape, in almost impossibly precise framing, is filmed during myriad seasons and weather conditions as its subject decays. It’s a fun setpiece, but serves to underscore how Pálmason seems more intent on announcing and elevating his own auteur status than in engineering a consistent and self-sustaining film world. That all said, it’s a fully realized movie with no sign of compromise or mitigation, which in its own right is a striking and pleasant thing to behold.

Albert Serra’s Pacifiction is the other best example I’ve encountered of an object made by a filmmaker who’s managed to step up his game this year. It’s a movie, like Pálmason’s, infatuated with—verging on obsessive over—its setting and that setting’s history and landscape. Not nearly the transgressive provocation that Serra has become known for (namely and most recently Liberté, his libertine S&M cine-painting that premiered in Cannes’s Un Certain Regard sidebar in 2019), Pacifiction is a different, in some way even more mischievous form of difficult, precisely because it’s the closest thing he’s made to a conventional film. The film is centered on De Roller (Benoît Magimel, who lately appears to have begun transmorphing into Joe Pesci), the High Commissioner of Tahiti in French Polynesia, who reacts to a barrage of rumors that France intends to imminently resume nearby nuclear testing. He struts around the island, through its Paradise Nights nightclub amongst various state officials, members of the Marine Nationale, Serra’s muse Lluís Serrat (silent and sleepy as ever) and a small clique of recurring characters, instigating conversations about societal rot, the benefits of genocide, his longing for the enlightenment of the 18th century and his musings on the incompatibiilty of emotion and rationality—sentiments that will be familiar for anyone already acquainted with Serra’s sensibility.

Loquacious, tedious and compulsively watchable, Pacifiction shows Serra in full command of his craft, and coasts on the tension between its implied political material and the sensuous atmosphere and images. Serra collaborates here again with DP Artur Tort (after Roi Soleil [2018] and Liberté), whose camera grazes over the movie’s strange network of scenes with the Michael Mann-infused vibe of a groggy luau—powerful people doing powerful things, because they’re glowing and well-dressed while doing so. The film’s relationship between meaning and feeling is something I fought with for nearly 100 minutes, troubled as I was by an intrusive sense that Serra’s project wasn’t quite accommodated by this contemporary setting and ahistorical milieu. Without his previously preferred period setting and foundation as a guiding light, I found myself unproductively adrift in Pacifiction’s stream of expertly staged discussions and wanderings, unsure of how or why any person or image on screen related to whatever the movie’s ideas were. Ultimately I hardly cared, won over as I was by the film’s singular and utterly sublime UFO of a final act, which retroactively eased the previously scaffolding into place, and allowed me to trust—if not quite appreciate—it.