Back to selection

Back to selection

Cannes 2025: Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning; Eddington; Sirât

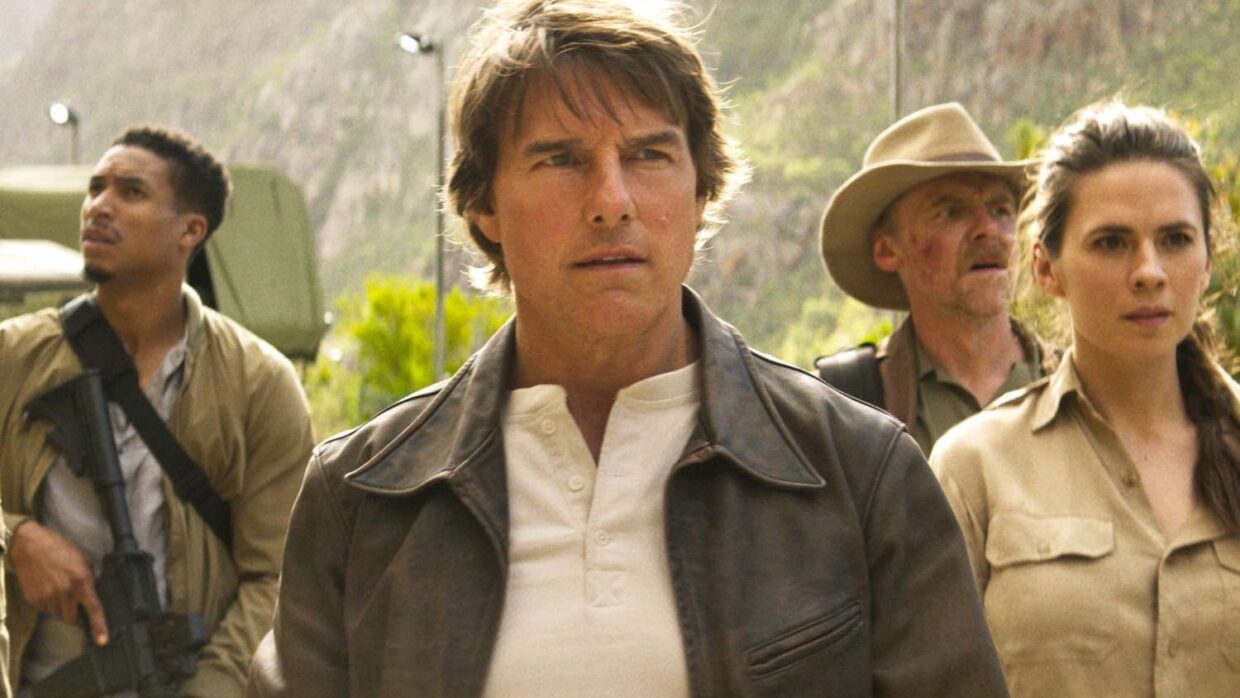

Mission: Impossible — The Final Reckoning

Mission: Impossible — The Final Reckoning Eight years after Cannes dipped its toes into VR waters with their presentation of Alejandro González Iñárritu‘s ultra-haptic empathy machine Carne y Arena (2017), the festival’s general delegate Thierry Frémaux continues to promote cinema’s expanding XR toolbox. In addition to bringing back the festival’s Immersive Competition for a second year—from what I saw of the press tour held a few hours before the Opening Ceremony, it would be difficult to justify a third—Frémaux also, per an interview with Screen International, trained this year’s festival staff using an AI version of his own voice when he couldn’t be present to address them himself. Despite the increased productivity and efficiency this technology no doubt afforded him, he maintains his wariness: “It doesn’t just concern cinema. We’ll have to tread carefully.”

A day later, in the now Dolby Atmos-equipped Grand Theatre Lumière, the most high-profile premiere of this year’s edition arrived in the form of Christopher McQuarrie’s Mission: Impossible – The Final Reckoning, the second part of 2023’s Dead Reckoning, in which Ethan Hunt (Tom Cruise) attempts to save humanity from a sentient AI called the Entity. The eight films that make up the nearly 30 year-old franchise have been among contemporary cinema’s louder answers to the rise of digital fakery; even with the last two M:I films ditching celluloid completely, the insistence on practical stunts over CGI or green screen has become one of these films’ biggest selling points, even if it has resulted in broken bones and, consequently, cost millions in production delays. The point is that our increasing reliance on computers has eroded truth and driven us all insane, and winding back the clock on this front would be nigh—you got it—impossible.

The commitment to the material world is appreciated, even as the thrills provided by watching Cruise take actual risks is possibly as minimal as ever here. The man is approaching retirement age, and I’m more than fine cutting him some slack; however, I’m less inclined to be generous toward McQuarrie and his co-writer, Erik Jendresen, who structured this (together with Dead Reckoning) five-and-a-half hour-long swan song around endless blocks of exposition. A gadget is only cool if the audience is first told how it works, I understand that, but McQuarrie and Jendresen allow this strategy to infiltrate every element of the plot. Their approach to information-delivery is extreme, as they opt to have virtually all of the movie’s future events described in such detail that their eventual arrival feels like an abstraction. When it’s expressive, it works: I’m guilty of getting choked up by the protracted supercut that opens Final Reckoning, which is as slick and kinesthetic as anything else in the film, and functions less as plot catch-up than as a temporal collapse of Hunt’s (ie. Cruise’s) aging body and our memories of the way these movies operate when they’re at their best. Jump ahead to the movie’s climax (only two days later, I struggle to recall much else)—a race against a 20-minute countdown in the diegesis takes at least 30 minutes of cinema time to transpire—which slips this series’s finale into a poetic realm. All the foretold insurmountable tasks, stakes and comically low-percentage movements required to save the world begin to lock into place, demonstrating how the time required to think critically is often greater than that which we are given to work with.

As the lights dimmed for Ari Aster’s pandemic-era satire, Eddington, my viewing companion muttered under his breath, “Nobody better clap for the A24 logo.” That logo was followed by a single clap that quickly went audience-viral and swelled to hearty applause, which itself was then combatted with a smattering of boos. The audience was already divided, perfectly setting the stage for the film’s both-sides-ist indictment of virtually every culture war currently being waged in America. Set in the fictional New Mexico town of Eddington toward the beginning of the COVID-19 outbreak (circa late May 2020), the movie is a kaleidoscopic portrait of a fraught mayoral election. The electorate’s options are limited to the sitting mayor, Ted Garcia (Pedro Pascal)—his campaign slogan, “Paving the Way for a Tech-positive Future,” alludes to his campaign promise to develop a hyperscale AI data center that will bring jobs to the area—and local sheriff Joe Cross (Joaquin Phoenix), whose candidacy kicks off after he begins to ardently defend the community’s fellow anti-maskers. The film takes no prisoners, portraying both the town’s woke mobs and its right-wing conspirators as absolute morons who’ve fallen victim to outrage porn.

Aster’s trajectory from the elevated horror of Hereditary (2018) and Midsommar (2019) to anxious diagnoses of the American id (Beau Is Afraid and now Eddington) is a familiar path for the Great American Directors—including, more recently, Paul Thomas Anderson’s early mid-career turn from ensemble theatrics to There Will Be Blood (2007), The Master (2012) and Inherent Vice (2014). (Joaquin Phoenix’s participation in most of these titles only strengthens the connection.) I’ll admit that Aster’s slide into politcal satire feels a bit forced to me, though I also feel that the awkward fit of his sensibility on this direction has yielded a curious atonality. At its worst, Eddington evokes the facile social commentary of Don’t Look Up (2021), while at its best it calls to mind the violent and unrelenting nihilism of Cormac McCarthy. I won’t be joining any chorus decrying Aster’s “self-indulgence” here—as if art, and indeed cinema, would have ever evolved at all without our most indulgent artists’ flights of fancy—but I do think he’d benefit from being a little less comprehensive.

Comparatively, Oliver Laxe’s Sirât is a stark work of minimalism. After an onscreen quote references the Sirât Bridge—a line between paradise and hell as thin as a thread and sharp as a sword—we are dropped into a freetekno party somewhere in Morocco’s arid desert landscape, as an arriving techno beat from Berlin-based composer Kangding Ray flexes the theatre’s Atmos muscles even more exhaustively than McQuarrie did. Laxe moved to the North African country shortly after finishing his debut feature, You All Are Captains (2010), and has since “deepened [his] relationship with the Islam and the Muslim mysticism, the Sufism.” The writhing bodies in this opening passage wouldn’t be mistaken for Sufi whirling, though the corporeal transcendance displayed here is in step with the religious practice’s psychedelic leanings. Cinema’s commonalities with music remain undervalued, and for a good while I wondered if (and indeed, desperately hoped) this scene of spiritual reverie might be sustained for the entire two-hour running time. Alas, reality kicks in, and Laxe eventually trains our attention on Luis (Sergi López) and his son Esteban (Brúno Nuñez), who weave through the party in search of Luis’ missing daughter, Mar, who they hoped might be in attendance. She isn’t, but they encounter a woman named Jade (Jade Oukid) who tells them about another party that will occur across the Western Sahara berm in a few days, which she and a few of her friends will be trekking to in their camper vans. And off they go.

To my surprise, Sirât’s success, which initially seemed predicated on either its thumping sensual pleasures or the catharsis of its search narrative, is ultimately achieved by Laxe’s subversion of these genres and tropes. (The film I keep going back to as I reflect on the movie is Kelly Reichardt’s 2010 anti-western Meek’s Cutoff.) The nature of its deviations are best discovered while watching the film itself, but I can say I was thrilled that I was forced to constantly revise my imagination of the movie’s destination. Narrative movies are so often dependent on satisfying viewers’ desire for images we’re already comfortable with, so if was a relief to see one that argues—quite literally, in the end—for not thinking, for finding our way by closing our eyes. It’s the second film by a Galician filmmaker in recent years to encourage this unorthodox mode of vision (the other, Lois Patiño’s 2023 film Samsara, will be best remembered for its flickering 15-minute intermezzo, during which viewers are instructed to actually close their eyes to watch the movie), and it’s a liminal space I’d be more than happy to keep being immersed in.