Back to selection

Back to selection

Into the Splice

Adventures of a film spectator by Nicholas Rombes

Into the Splice: Machete

It was only later that I discovered that I had been charged admission to Machete as a “student.” I am not one, and haven’t been for many, many years. I was glad not only because it saved me two dollars, but also because I didn’t have to resort to the Harvey Korman moment near the end of Blazing Saddles, when he cuts in line to buy a ticket for the film itself, pulls out an I.D., holds it up with a skeptical smile and asks the ticket lady, “Student?” to which she replies flatly, “Are you kidding?”

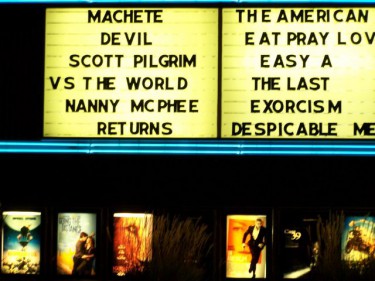

At 9:30 on a Saturday night, the Cineplex is a jittery beehive of teenage triumphalism. I’m there with a film-buff colleague, and I feel a bit guilty and out of place, as if I’ve been let into a secret world by mistake. A violent thunderstorm rattles the lobby, the lights flicker, and for a moment we’ve all exchanged our real lives for our movie lives, and we’re extras in a film called Blood Zombies, about a bunch of people trapped and hunted in a Cineplex. Machete is playing in one of the smallest auditoriums, down a far hall and around a corner, next to the exit that no one ever uses.

The film begins, and before not too long the title delivers on the goods, as Machete (Danny Trejo) hacks his way through villains and into a trap, the blood spurting across walls and doors and windows and floors. The machete is the ultimate film cutter, slicing across and through the axis of action, redistributing body parts, to each according to his need. The theater practically sloshes with blood, gallons of it waterfalling down the aisles, soaking our shoes. And then it’s quiet again, as Booth (Jeff Fahey) offers a suitcase full of money to Machete to assassinate Senator McLaughlin (Robert DeNiro).

The film begins, and before not too long the title delivers on the goods, as Machete (Danny Trejo) hacks his way through villains and into a trap, the blood spurting across walls and doors and windows and floors. The machete is the ultimate film cutter, slicing across and through the axis of action, redistributing body parts, to each according to his need. The theater practically sloshes with blood, gallons of it waterfalling down the aisles, soaking our shoes. And then it’s quiet again, as Booth (Jeff Fahey) offers a suitcase full of money to Machete to assassinate Senator McLaughlin (Robert DeNiro).

By the time he says of himself, “Machete don’t text,” we are fully on his side. We have been sutured into the film, into the splice, adopting Machete’s point of view, and it is a wonderful thing, to hold that machete in our hands, to wield it on the enemies of goodness in this world. Don Johnson as Von Jackson, the vigilante border agent, is the sort of character whose presence on the screen is an annihilating force. When he’s on the screen he slows down time. When he talks, he might as well be in an Antonioni film. His evil penetrates the screen. There is nothing funny or campy about Von Jackson. He is an extreme version of something in all of us.

Don Johnson’s performance creates an open space in the film, a space in which to think. He delivers his lines slowly, like some imagined prophet. In the theater, I wonder about the contradictions. Here is a film with an explicitly “political” point of view (all films are political on some level) whose dark view of the American political system is nonetheless financed, in large part, by the capitalist machinery of Overnight Productions, founded several years ago by Rick Schwartz who, according to Mike Fleming at Variety.com, “plugged in with a network of private equity and high net worth individuals.” This contradiction, of course, is inherent to capitalism: as long as there are profits to be had, no subject is taboo, even if the subject is the evil of making profits. Machete is not a film about the evil of making profits, but it is a film about immigrants taking up arms against those who would restrict their flow into the US.

But what’s been lost in much of the coverage of the conservative anger over the film’s portrayal of the immigration debate is the fact that the film was distributed by 20th Century Fox, which is owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., not exactly a corporation associated with lines like “We didn’t cross the border. The border crossed us.” And yet Murdoch, recognizing the value of cheap labor, has spoken recently in favor of amnesty for illegal immigrants, saying that “this country must enact new immigration policies that fulfill our employment needs.” These contradictions are there in the deep structures of the film itself, as it rock blasts genres—exploitation, revenge, satire, comedy, slasher, soft-core—into some new stew, unencumbered by the limitations of a particular style or tone. Rodriguez’s genius has always been to worm himself into a genre and turn it inside out.

But what’s been lost in much of the coverage of the conservative anger over the film’s portrayal of the immigration debate is the fact that the film was distributed by 20th Century Fox, which is owned by Rupert Murdoch’s News Corp., not exactly a corporation associated with lines like “We didn’t cross the border. The border crossed us.” And yet Murdoch, recognizing the value of cheap labor, has spoken recently in favor of amnesty for illegal immigrants, saying that “this country must enact new immigration policies that fulfill our employment needs.” These contradictions are there in the deep structures of the film itself, as it rock blasts genres—exploitation, revenge, satire, comedy, slasher, soft-core—into some new stew, unencumbered by the limitations of a particular style or tone. Rodriguez’s genius has always been to worm himself into a genre and turn it inside out.

And Machete is an inside-out film. There is nothing internal to any of the characters. In the audience, I felt my own self emptying out, and joined the characters on the screen. I certainly joined April (Lindsay Lohan) in her nun’s habit, undergone some sort of inscrutable conversion, wielding her weapon as if it spoke with the full force and power of the historical Church.  April is the most completely scrambled, haunted, incoherent character in Machete, and maybe for that reason the most mysterious. She doesn’t give speeches about immigration or killing or revenge or survival or national pride. Instead, she spots a nun’s habit in a church and wears it like an exterminating angel. The Village Voice said that Rodriguez’s films “regularly show an indifference to linear logic” and that Machete in particular has “no real character drama.” At least half the great films that I can think of lack one or both of these attributes, while many terrible ones have them both. April must have really stuck in the craw of The Village Voice reviewer, because she is so much not a dramatic character that her part is practically an avant-garde performance.

April is the most completely scrambled, haunted, incoherent character in Machete, and maybe for that reason the most mysterious. She doesn’t give speeches about immigration or killing or revenge or survival or national pride. Instead, she spots a nun’s habit in a church and wears it like an exterminating angel. The Village Voice said that Rodriguez’s films “regularly show an indifference to linear logic” and that Machete in particular has “no real character drama.” At least half the great films that I can think of lack one or both of these attributes, while many terrible ones have them both. April must have really stuck in the craw of The Village Voice reviewer, because she is so much not a dramatic character that her part is practically an avant-garde performance.

Which leads us to the end, the credits, the emptying theater, the lobby with its scattered midnight-showing patrons, the harvest moon hanging like a super low-watt bulb over the parking lot. At home later, in the deepest of night, images from Machete trail me around and I know that if I go to sleep I’ll dream of Machete and those sacks beneath his eyes, and of the blood-spattered walls like Jackson Pollock drips, and of April in all the superbad glory of her habit, aiming her weapon at me and firing, my heart accepting the bullets like they were love letters.

Nicholas Rombes is author of Cinema in the Digital Age and A Cultural Dictionary of Punk, 1974-1982. His work has appeared The Oxford American, the n+1 Film Review, and McSweeney’s Internet Tendency. His column, 10/40/70, appears at The Rumpus. He can be found at nicholasrombes.blogspot.com.