Back to selection

Back to selection

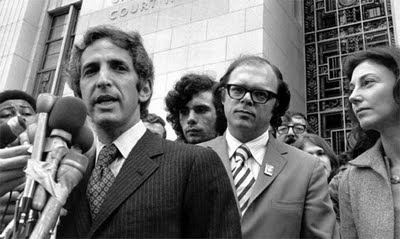

Judith Ehrlich And Rick Goldsmith, The Most Dangerous Man In America

As a history lesson, Judith Ehrlich and Rick Goldsmith’s enthralling new documentary, The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers, is as solid as a textbook, stitching together old broadcast footage, first-person testimony, tart excerpts from the Nixon White House tapes, and noirish recreations into riveting, revelatory political drama. The name “Daniel Ellsberg” probably doesn’t trigger the same flurry of associations as Deep Throat, the shadowy antihero of the Watergate scandal, but it should: An ex-Marine, former assistant to Secretary of Defense Robert S. McNamara, and highly respected analyst at the Rand Corporation, Ellsberg leaked a 7,000-page study detailing the top-secret Southeast Asia policies of five presidential administrations to the New York Times, resulting in a landmark court case, attempted cover-ups, and a nasty smear campaign, all culminating in the ignominious resignation of President Nixon. To be sure, the spy-grade story of the Pentagon Papers controversy has a lot of rich angles, including government secrecy, first-amendment rights versus executive privilege, and the rise of the national security state. But it’s also a conversion tale deeply concerned with the burden of conscience that Ellsberg felt as a government insider to tell the public what he believed they had a right to know, and his desire as a newly minted dove to change the course of the Vietnam War.

Part journalistic exposé, part overdue homage to one of the last century’s most notorious whistleblowers, Most Dangerous Man is a pressurized piece of filmmaking, resonating with issues (civil rights, the press, the conduct of war) still worrying the national conscience. With considerable flair backed by exhaustive research, Ehrlich (The Good War and Those Who Refused to Fight It, 2001) and Goldsmith (Tell the Truth and Run: George Seldes and the American Press, 1996) guide us through the corridors of power where the Vietnam war was seeded and then bloomed, often against the private advice of military analysts. Ellsberg himself provided McNamara with evidence of “atrocities” that helped push the war along, then reversed course after a two-year stint in Saigon with the State Department convinced him it was not only a lost cause, but a moral travesty based on years of prevarication. Seen then and now, he emerges as a man of principle, sincere and articulate. His fascinating chronicle of that time is augmented by a carousel of outspoken interviewees, including old colleagues like Anthony Russo (the Rand associate who persuaded him to Xerox the papers), Nixon officials John Dean and Bud Krogh (who authorized the break-in at Ellsberg’s doctor’s office), and general counsel James Goodale, who soothed the nerves of the Times’ top brass. Winner of the Special Jury Award at IDFA, and recently shortlisted for the Oscar, Most Dangerous Man is able-bodied and slyly entertaining, and has plenty to teach us, especially in these times, about the power of dissent.

Filmmaker spoke with Ehrlich and Goldsmith about crises of conscience, fair-use issues, and why you won’t be seeing Dan Ellsberg on any talking-head news programs.

The Most Dangerous Man in America: Daniel Ellsberg and the Pentagon Papers opens Friday at Cinema Village.

Filmmaker: How and why did you decide to anchor the film around Daniel Ellsberg’s narrative and personal voice as opposed to approaching the story of the Pentagon Papers leak from a more general point of view?

Ehrlich: It was something we struggled with a lot. I always wanted it to be more character-driven and more biographical, not just a generic story about the events. The idea of whether it would be Dan’s voice or not was still up in the air until very late. I think Rick wanted it to be more journalistic and objective, but we compromised. I always felt [his voice] would make it a stronger narrative. For one thing, Dan lives right near us, he’s extremely articulate, his writing is wonderful, and most of the narration is adapted from his [book]. To me it seemed a no-brainer not to use him—it would give it that much more authenticity. But I think Rick’s points were legitimate, so that was a complicated decision.

Goldsmith: I’d actually approached him with a film about the Pentagon Papers and it didn’t get off the ground. Then Judy came to me about a year later with a film about Dan Ellsberg. Some of the initial questions were, Do we have a film about him or do we zero in on the Pentagon Papers? The personal transformation story, obviously, was the kickoff for the whole event, and we spent over a third of the film on that, and then got into the event itself. I don’t know if “morality play” is the right word, but it triggers questions of conscience, not only in Dan Ellsberg, but in so many of the characters that we have onscreen, starting with Randy Kehler and then leading to the newspapersmen, Hedrick Smith and Max Frankel, the Times lawyer, and the congressman. They all had crises of conscience. The Nixon administration, people like John Dean and Egil Krogh, all had to face very big questions that hopefully we all face on some level.

Filmmaker: Was Ellsberg amenable to participating when you first presented the idea, or were there negotiating points in terms of how his story would be told?

Goldsmith: It was a process. We approached Dan when he appeared onstage before a local high school in Oakland with his wife Patricia, where they talked about their remembrances of that time. That was the first time we talked face to face with him about it. He had had other filmmakers approach him about the subject matter, [but] he had not wanted to do anything until he wrote his own account [Secrets: A Memoir of Vietnam and the Pentagon Papers], which he did in 2002. This was late 2004, when we spoke. He was protective of his story, for sure, and wanted to know what we would do with it, so it was not a slam dunk that he was going to go with us.

Ehrlich: Also, I think there was an intervention by some mutual friends too, who made them feel like we would do a fair job. But I think they had reason to be nervous, because Dan had had a hatchet job done on him by an author. F/X had done a made-for-TV version of the Pentagon Papers, with James Spader playing Dan, except [the producers] never talked to them, they cut them entirely out of the process. I don’t think they felt burned by that, but they certainly were cautious. We were lucky they chose us.

Filmmaker: There’s a confessional aspect to the film that calls to mind The Fog of War. Was this another opportunity for Ellsberg to set the record straight in a different medium?

Ehrlich: Dan’s very quick to accept guilt. That was his motivation for doing what he did. There were moments when we had to be sure we didn’t look too much like Fog of War, because it was the same period, with similar characters. There’s a lot of resonance here between the two films, and we wanted it to feel different.

Goldsmith: I don’t think Dan needed to unburden himself. I think he felt deeply about what he had done, planning the war and helping it along, and he felt very passionately [that leaking the papers] was the right thing. I think he was intrigued with the idea of somebody other than himself telling the story, and was ultimately convinced we would do it justice.

Filmmaker: How long did it take you to gather all the archival footage, as well as selections from the Nixon tapes that were used in the film? Did you have issues with clearances?

Goldsmith: It took four years. The archival stuff started with articles from the time period, and then we went to D.C. to do some filming in 2007. All that broadcast material of Howard K. Smith and Walter Cronkite is in the National Archives, because somebody in the Nixon administration was given the job to tape the nightly news and every public-affairs program. The Nixon tapes were also there, and it took a lot of digging and research by our team to get them. Those were free, but with a lot of the broadcast material, it was kind of an unknown whether we could claim fair use. Often we did, and used that as a way to not break our budget. We also spent a lot for CBS News, which was probably our biggest check, for their footage on the war and everything else.

Ehrlich: We had a very interesting experience with the fair-use issue. I don’t know how much you’re familiar with Pat Aufderheide and that whole movement, to make that more clear and get filmmakers the right to do it legally. We used a lawyer, Lisa Callif, and she went through every single clip a number of times and confirmed that each one of them was within the “safe harbor” of fair use, as she called it. And the quality was good enough we could go straight into DV-cam. I think that’s a great opportunity for anyone who’s looking at this period, to be able to access that material.

Filmmaker: In terms of visuals, the graphics, animations, and cloak-and-dagger-style recreations add another layer of tension and moody suspense. Were those part of your original plan for the film, or did they come later in the process?

Ehrlich: I think we were a year into editing by the time our assistant editor, Lawrence Lerew, came up with the recreation idea. I jumped on the bandwagon immediately and worked with him. It took a long time for Rick to decide it was going to work. So we did a bunch of rough versions and eventually we all got on board.

Goldsmith: The recreations and animation were the last productions we did. For obvious reasons, you want to to have every piece in place and know what part of the story you can [illustrate]. It’s true, Judy was pushing more on that. I like the idea of recreations, but the extent to which we ended up with them, I was skeptical at the beginning. I was concerned with losing a little bit of credibility [if we made it] too first-person. It was a process. But because there were a lot of creative minds on it, it worked.

Filmmaker: You’ve corralled quite a roster of talking heads in this film. John Dean and Bud Krogh’s participation seems essential, given their role in the Fielding break-in. Were there other key players you sought to interview who didn’t make it onto film?

Goldsmith: The idea from the beginning was to get as many people [as possible] who were really there. You’ll notice there are very few people onscreen who didn’t actually participate in this story. Robert Ellsberg, Daniel’s son, was Xeroxing the Pentagon Papers so we went after him. Mort Halperin was head of the study so we went after him. We wanted to get Kissinger and couldn’t get a call back, and we wanted to get Alexander Haig, who was peripherally involved.

Filmmaker: You did get Kissinger virtually.

Ehrlich: We actually made him look good! [Laughs] That’s the one thing I kind of regretted about the film. He’s the voice of reason compared to his boss.

Goldsmith: One of the people we tried hard on, and I had at least four or five conversations with on the phone, was Harry Rowen, who would have been a very interesting interview. That was Dan’s boss at the Rand Corporation. He got the shit when the leak happened. I’m sorry that we couldn’t win Harry over to agree to be on camera. But we tried really hard.

Filmmaker: Considering that both of you come from television, what was different for you about the experience of making a feature for theatrical release?

Ehrlich: We were funded by ITVS, German and French television, so we always were making a film for [that medium]. When we saw the animal we had, we hoped it might be theatrical, but we certainly didn’t make it primarily for theatrical release. It had to be public television because we had their money.

Goldmsith: What happened along the way was that among ourselves, through Lawrence, we started to branch out and see more of the creative [elements] that could elevate it beyond the standard documentary. In May or June, even though we were very close to a final cut, we learned that Karen Cooper at Film Forum was interested in the film—we had sent her a rough cut—and also the Toronto Film Festival. However, we had already fashioned it as a more dramatic, dynamic show. We sensed down the home stretch that, hey, this thing is bigger than a TV or educational thing, and we need to make the most of it.

Ehrlich: What surprised me is the interest we’ve had with the film internationally. It won the Special Jury Award at IDFA in Amsterdam, which was really exciting and a huge surprise, since that’s the biggest documentary festival in the world. And we also have had amazing sales around the world. We didn’t think this film would really play that well outside the U.S., but it’s really striking a chord.

Filmmaker: What do you think is registering with people internationally?

Ehrlich: I think people want to hear a positive story about American conscience. [Laughs] We get so much bad press and people in Europe at least are crazy about Obama, they aren’t feeling the negative feelings that we’re having here as progressives at the moment.

Goldsmith: It has a universality to it. The crisis of conscience and the historical stage — it’s the Vietnam War, leading up to Watergate. I like to believe that the film’s pretty well made, too, but the story resonates on a lot of levels that transcend borders.

Filmmaker: Another part of the film deals with the power of the press and the conflict with executive privilege that Nixon invoked in trying to halt the Times’ reporting. It seems to have an extraordinarily urgent resonance today, with the folding of so many papers and news organizations struggling to develop new business models to stay alive.

Goldsmith: I think it points to a time when news organizations defied the government and that, too, I think gives people a sense of what can be done. To me, [it’s amazing] that young people don’t know this type of story, when citizens rise up and do something, when newspapers defy their government and print stories that their government not only doesn’t want them to print, but then goes to court to stop them.

Filmmaker: What were the biggest discoveries that you made in researching this film and interviewing the participants?

Ehrlich: For me, it’s the Watergate period, because I thought I knew that. One of the gifts of this film is that we have reinterpreted the history of Watergate in a more accurate way because of John Dean’s testimony, if we’re to believe his interpretation that it was the break-in to Dr. Fielding’s office, rather than the events of Watergate, that really brought down the Nixon administration. When we first started I thought, “Oh yeah, and it kind of has something to with Watergate, too, because the Plumbers started there and then they did the real thing nine months later.” But in fact the break-in at Ellsberg’s psychiatrist’s office was what brought [Nixon down], because that could be tracked back to the White House.

Goldsmith: For me, it was the extent that Daniel Ellsberg was not only inside the government, but actually took part at the top levels. He has incredible knowledge about how the government works, how the secrecy system works, how organizations like RAND work, and he has an incredible amount to add to the public debate about issues of war. We don’t hear [his voice], we don’t see him on the TV shows. Every time we’re about to go to war, from the first Gulf War to the Iraq war to Afghanistan, you see all these retired admirals and generals, but you don’t see the Daniel Ellsbergs who have as much information about government because they’ve been there. To me, learning that, learning how much he knows, was one revelation, and the other was how much he’s been shut out from public debate. And that’s a loss for all of us.

Filmmaker: So who’s the most dangerous man in America today? Is it still Dan Ellsberg?

Ehrlich: It could be. What he has to say is still pretty scary to the government.

Goldsmith: I think at that time, Dan did do this incredible act, but let’s face it, there was an entire anti-war movement that should not be forgotten. He didn’t exist in a vacuum.