Back to selection

Back to selection

“THE CANAL STREET MADAM” AT STRANGER THAN FICTION

Last night’s Stranger Than Fiction, the weekly documentary series at the IFC Center, “completed a circle” for programmer Thom Powers. It was while Powers was judging applications for the Garrett Scott Documentary Development Grant, a grant given by the Full Frame Festival in honor of the talented filmmaker who passed away at the age of thirty-seven, that he first learned about Cameron Yates’ film, The Canal Street Madam. As part of their grant proposal, Cameron Yates and producer Mridu Chandra had submitted a ten-minute reel of highlights from their work-in-progress. The footage impressed Powers, and he selected them as one of the two projects to receive that grant, just one of the many small victories in Yates’ six-year fight to make his film.

Last night’s Stranger Than Fiction, the weekly documentary series at the IFC Center, “completed a circle” for programmer Thom Powers. It was while Powers was judging applications for the Garrett Scott Documentary Development Grant, a grant given by the Full Frame Festival in honor of the talented filmmaker who passed away at the age of thirty-seven, that he first learned about Cameron Yates’ film, The Canal Street Madam. As part of their grant proposal, Cameron Yates and producer Mridu Chandra had submitted a ten-minute reel of highlights from their work-in-progress. The footage impressed Powers, and he selected them as one of the two projects to receive that grant, just one of the many small victories in Yates’ six-year fight to make his film.

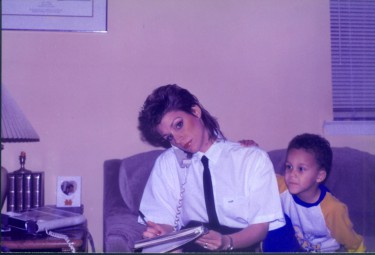

An unflinching portrait of Jeanette Maier, a woman made famous for running a brothel that serviced the New Orleans elite and made infamous for allowing her daughter to work there as a prostitute, The Canal Street Madam follows the former madam as she seeks to make a life for herself post-prison. As she struggles financially, she becomes an advocate for sex workers, speaking out against the legal system that put her in prison but keeps her former clients in higher office.

A smartly complicated text, The Canal Street Madam somehow manages to agree with Jeanette that the laws need to be changed without entirely buying her claims that her children’s problems (which are vast) can be entirely blamed on the legal system instead of her own party lifestyle. As her daughter says, her mother used certain tools to survive, and she “laid those certain tools in my hand.” Admirably non-exploitative, The Canal Street Madam is nonetheless a provocative tale that allows a complex woman to tell her story in her own words.

I spoke with Yates and Chandra before the screening.

Filmmaker: Which came first — your interest in prostitution or your interest in Jeanette?

Yates: I had been really interested in sex workers and the sex industry for quite some time, mainly about it as a viable business model. I had heard about Jeanette’s story and how she was running a brothel with her mother and daughter, and it fit into what I’d been reading about the history of New Orleans madams and their connections to local politicians…Also, it really fascinated me how the media blew this story out of the water.

Chandra: There have been a lot of documentaries about madams, but there hadn’t been a story about what happened after they got exposed. For me, it’s not about right or wrong, it’s more about hypocrisy. That’s an angle that’s uniquely American. I wanted this story to get out there.

Filmmaker: Cameron, talk about how you shot this documentary. Were you shooting with a crew or were you approaching it one-man-band style? Did you know that you were going to get a feature out of it?

Yates: When I first started working on it, I wasn’t quite sure what it would be. I just knew I had a fascinating subject. When I met Jeanette for the first time, we talked, well, I should say she talked, for hours and hours. We had an immediate rapport. I would travel down to New Orleans on flights that were $69 each way. It was just me and the camera. It was three or four years before Mridu got involved.

Chandra: I had worked with Cameron once before. (While in film school, Yates had assisted on the ITVS documentary, Let the Church Say, Amen, which Chandra produced). I ran into him at a party, and I realized listening to him talk that he was really serious. We spent a day together, and he showed me some scenes…We spent time talking about what the goals were for the project and our understanding of the issue…It’s so much work to make a film where funding is an issue, so it’s worth spending the time to make sure you’re always on the same page.

Filmmaker: Cameron, all those years when you were shooting without a producer, how did you keep up the drive to follow the story all on your own?

Cameron: I really was just very passionate about Jeanette and her story and the project. I was just shooting and had no idea how long it would take. It was easy to do because I had a camera… I had other income coming in, so I would just work on in throughout the year. The production aspect was a lot less financially taxing than the post-production and pulling everything together together on that end.

Chandra: You’d like to be funded from the get go, but especially now, funding is harder and harder to get from the very beginning. You have to show almost a rough cut before you get your funding.

Filmmaker: Woven into the text of the film are excerpts from phone calls Jeanette was making while working as a madam. How did you get access to this material?

Cameron: So, essentially the phone calls are the FBI wiretaps of Jeanette’s phones. They were wiretapping her home phone, the brothel phone, her cell phone and her mother’s phone. These calls were made public during Jeanette’s trial, so Jeanette and her lawyer had access, and she gave them to us. The first time she listened to them, she found out crazy things about her son and daughter’s sex lives. To me, it was important to pull out the relationship between mother and daughter as well as the clients and Jeanette. Mridu and I got caught up listening to them for days and days. We went through everything and highlighted the most interesting.

Chandra: The film really starts after the business is over… It was valuable to hear the story of the business, and it seemed pretty important. It also provides an undrstanding of what the demand side wanted, what men call about when they call a brothel.

Filmmaker: There’s a lot of landscape footage of New Orleans in the final cut, and I wondered if you were conscious of the fact that the film has two subjects, Jeanette and New Orleans itself?

Cameron: When I started in 2004 it was a year and a half before Katrina hit. I kind of went back and forth because we didn’t want the film to become another Katrina documentary, but it was around that time that Jeanette got out on parole… New Orleans has always had this draw to me. It’s a city outside of the rest of the country, and a place that allowed Jeanette’s business to thrive. We realized in the edit that it should have that city arc.

Chandra: Her story, her life, all of it comes from that place.

Filmmaker: You shot over many years. How much footage did you end up with?

Yates: It ended up being around 120 hours.

Filmmaker: That seems low. You hear about these docs where people have shot over 250 hours over several years.

Chandra: He tried to go down to New Orleans when it mattered. He was thoughtful, and it really made a big difference in the edit.

Filmmaker: During the course of filming, David Vitter, the Louisiana Senator is exposed for being a client of the D.C. madam, and Jeanette announces publicly that he was a client of yours. What’s it like to be caught up in a real scandal?

Yates: When I heard that Jeanette and Debra Jean (the D.C. Madam) shared clients, I knew we had to be there. Vitter is up for reelection in a couple of weeks, so the premiere of the film this weekend in New Orleans and the Stranger Than Fiction screening couldn’t be better.

Chandra: He was not held accountable in any legal way for his actions, although Debra Jean and Jeanette were, and I hope that’s something our film speaks to.