Back to selection

Back to selection

The Microbudget Conversation

We're Only Talking a Few Thousand Dollars by John Yost

The Microbudget Conversation : Art And Poverty

This week I leave you in the capable hands of our editor Scott Macaulay. One of the exciting aspects of this gig is learning from a fella like Scott. A producer of some of my favorite indie films, he has been a great mentor and producer of this column. I asked him to just go nuts and write what was on his mind. Voila!

Last fall, I posted a call for new columnists for this website, and the first to respond was John Yost with the idea for this “Micro-Budget Conversation.” I liked John’s proposal for a number of reasons, the first being that I’m always looking for ways to cover more films from a curated perspective here. I liked that John would have a different eye, and even a different set of criteria, and that more filmmakers would be able to use the site to get the word out about their films.

But I also responded to the implicit question posed by this column, which was addressed directly in John’s first post, “What is Micro?” He wrote:

What is micro-budget filmmaking? What makes a film micro-budget? Is it simply the amount of money spent? Is it the quality of the story, image, and sound? Is it a cliché at this point? Where did it come from? What about the word “indie”? Is “indie” just a buzz word now?

I’ll rephrase this, and add to it: Does the decision to make a film at a resource level far below what is considered “industry standard” imbue the resulting film with some level of inherent value? Is there something noble about being a micro-budget filmmaker? Is micro-budget filmmaking — at least sometimes — a political statement? A social one?

Or, to put it more bluntly: is there a difference between being a micro-budget filmmaker and someone who makes very cheap movies?

Let me digress. Throughout history there have been connections between oppositional art movements and reduced resources. There have been artists for whom a rhetoric of poverty — or, perhaps more accurately, a rejection of the conventions associated with making art in more accepted (and usually more expensive) ways — has enabled empowering forms of self-definition. Some examples include Jerzy Grotowski’s “poor theater” — a stripped-down (i.e., cheap) dramaturgy that rejected the “hybrid spectacles” of “the Rich Theater” in favor of work based on the “essential communion” between the audience member and the live performer. Or, there’s the Arte Povera movement — a response by Italian artists to dire economic circumstances, but also a radical anti-capitalist movement that sought to redefine the relationship between art and life by embracing found and “poor” materials. The political motives of the Dogme ’95 film movement were playfully obscure, and though there was nothing in its “commandments” mandating a poor approach, the restrictiveness of these rules had the effect of producing sometimes radical work worn shorn of the fat of studio productions.

I’m sure a few people reading this are thinking, “Wait, there are plenty of filmmakers who curse their tiny budgets, who feel their films are compromised by them, and who can’t wait to graduate to bigger movies. An aesthetic manifesto is the last thing on their minds and is certainly far less important than making the day and having enough money for post.”

Indeed, most people who make micro-budget films do so without seeing themselves as part of any movement. To end my art history digression, I’ll say that I don’t think that just because you are working without a real budget that you have to be an avant-gardist, or politically oppositional, or a manifesto-writer… But I’ll also say that if there’s ever time to be one, it’s when you have the freedom that a small budget — and, hence, a lack of financial oversight — affords. In fact, I’d argue, that all micro-budget movies are served by creative rule-breaking — and at least a smidgen of experimental intent.

The least successful no-budget films have always been the ones made in the image of studio-budgeted models. These are the ones that embrace mainstream sensibilities without having the production budgets, star casts, re-shoot monies, music license fees, and marketing spends to make audiences accept them as mainstream. As Mike Ryan noted recently at Hammer to Nail, they are too indebted to Naturalism, and less willing to take the type of aesthetic risks that characterize not only the avant-garde but the pulp energy of the great old B-moviemakers. These indie films wind up neither fish nor fowl, not connecting with — or reaching — audiences while also not exciting the critics who expect in lieu of production value a different and original sensibility.

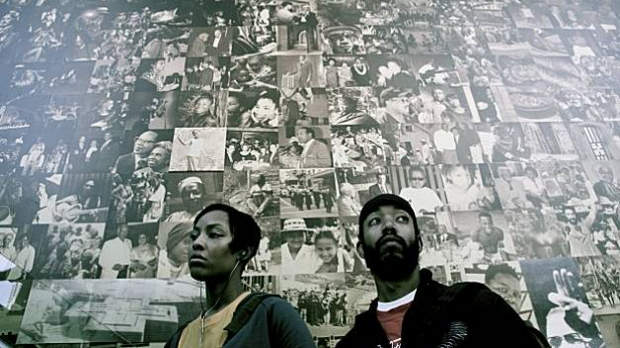

When I look back at some of my favorite micro-budget films of recent years, it’s always the bold experiments, digressive moments, or flights of fancies within them that I remember. When I watch these moments, I know the filmmakers haven’t let the opportunity afforded by their tiny budgets go to waste. For example, I love how in the middle of Barry Jenkins’ Medicine for Melancholy (pictured above) the camera glides away from the characters into a real-life neighborhood activist meeting on housing policy and sits there for several minutes, allowing the film to become at that moment a documentary about its very themes. Or when Ronald Bronstein’s Frownland takes a hilarious left turn, jettisoning all ideas of tidy structure by following a peripheral character who surprisingly reveals himself to be as disturbed as its nutso protagonist. I’m always knocked out by the dream sequences in the Safdie Brothers’ films (to say nothing about their poignantly shocking take on parenting). I was tremendously moved by Brent Green’s spoken narration to his stop-motion feature, Gravity Was Everywhere Back Then, when I saw it at The Kitchen. Knowing that Green had replicated the journey of his film’s protagonist by building a version of his house on his own property made it all the more crazily beautiful. I loved watching the recent Slamdance winner Without, which had all the elements of a “woman alone” babysitter thriller until director Mark Jackson reaches for an anti-genre ending that’s both heartbreaking and surprisingly tender. It’s been a couple of months since I saw Sophia Takal’s Green, but the way in which it told a story about female sexual jealousy through lush visuals and a psychologically attuned sound design rather than genre tropes stayed with me.

When I started writing this post I thought I’d write about films I’ve produced and link them to micro-budget practice, but I’ve gone on a tangent, and now the tangent has become the post. Also, out of the 15 or so films I’ve produced, five were for budgets under $1 million, but only one (Tom Noonan’s What Happened Was, shot on 35mm for $70,000 and winner of the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance in 1994) really falls within the micro-budget sphere. As feature producer first-timers, Robin O’Hara and I were wonderfully naive then about the kinds of things we think about today. We didn’t think about audiences, or a festival strategy, and we didn’t worry about how we were going to “open up” the great play the film is based on to make it more accessible. We had seen that play at Tom’s Paradise Theater, and we just wanted the film to be as amazing as that evening was for us. There was a lot of ambition in that 11-day shoot — complicated long takes that we’d burn film on again and again until they were flawless; performances that had to be, and were, pitch perfect; a subtle but labor-intensive color scheme change half way through the film to signify the more psychologically turbulent spaces the characters were moving into.

Experimenting, trying things, and not feeling creatively constrained because we didn’t have money — that’s what I loved as a producer about working with a micro-budget, and, as the editor of this magazine, that’s what I love seeing today’s filmmakers try. And I’m not alone. Sometimes it can take a while, but the bold films, the out-there films, the films that don’t feel like their creators have set foot in a multiplex within the last year — these are the micro-budget films that catch fire. So, if you’re making something for next to nothing, think about what you couldn’t do if you had more money and do that. Come up with your own definition of micro-budget cinema that’s fundamentally different than mainstream cinema, and make a movie that fits within it. Write your own manifesto. Be the star of your own movement. You’ll have more fun, and, in the end, you’ll make a better film.

-Scott Macaulay

I have made, and continue to make, the mistake of often trying to make aspects of my films like the big guys. Or adding way to much “Naturalism”. Sometimes it’s unavoidable…it seeps into your brain. But since the start of this column, I’ve been felling like there is a movement out there. We don’t necessarily need a written manifesto (although it would be pretty cool), but we do need to kick it up a notch in terms of embracing how free we truly are. Let us inject a little anarchy into the system and reinvent some of the norms. Let us turn and run from the instinct to someday join a broken system for a bigger budget, and start focusing on making some truly sincere cinema.

braveandthekind@gmail.com