Back to selection

Back to selection

“LETTERS FROM THE BIG MAN”: THE RETURN OF CHRISTOPHER MUNCH

Movie lovers with a prolonged case of the Munchies could soon be sated. Indie-pure director Christopher Munch is back, in fine form, with his latest film, Letters From the Big Man.

form, with his latest film, Letters From the Big Man.

Munch imbues his works with a distinct nostalgic longing. The Germans have a precise word for it: Sehnsucht. He explores that chaotic region where two forms of desire butt up against each other: the wish for a more perfect world, for one, usually depicted as majestic nature and whatever beauty man might have put into it (the old, deserted railroad in Color of a Brisk and Leaping Day) — an American version of classic German Romanticism, or blood and soil when taken to a nationalist extreme; and two, the physical attraction of one living being toward another. The latter might be a gay man’s unrequited feelings toward a disinterested straight man (The Hours and Times), or even two brothers for each other (Harry and Max).

In the case of the female protagonist of Letters From the Big Man, the magnetism is more complex. She feels sexual desire for a man and, accompanying the allure of painfully gorgeous landscapes, a much more ethereal yearning for the Sasquatch, the large, hairy, nearly invisible forest animal referred to pejoratively as Bigfoot.

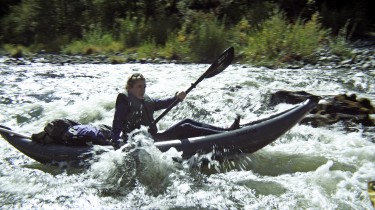

The film begins with Sarah Smith (Lily Rabe) stepping out of her charmless Medford, Oregon apartment (plus the painful end of a relationship) and the brutal concrete façade that separates her abode from life outside. From then on she exalts in the freedom of driving the open road and, at the end of her trip, the nearly virgin mountains, rivers, fir, cedar, madrone, and oak of the Klamath-Siskiyou Ecoregion in the Oregon Coastal Range. (Rob Sweeney’s fine cinematography and Ensemble Galilei’s haunting pipe-and-fiddle score perfectly highlight the appeal.) An employee of the U.S. Forest Service, Sarah spends a week, on her own by choice, collecting data to update a report on damage from a huge fire in 2002. For job and pleasure, she kayaks, swims, hikes, and jumps rope. She is rarely still, except when she sketches, which is frequently. She sees herself as an up-and-coming artist, and is in fact accomplished at landscapes and portraits.

Rabe’s performance is outstanding, even with few actors to work with or bounce off. The soaring conifers, pristine streams, and breathtaking peaks are her co-stars. Munch maintains a balance, filming Lily in medium shot or close up when revealing something about her conflicted inner life, in extreme long shot against magnificent vistas for a sense of her rapport with the natural world.

There is a payoff. The Sasquatch have decided to reveal themselves, oh so subtly, to Lily. At first they hide, stalking her, then they become more visible and communicate sub-verbally (though audiably for us), expressing admiration for her open heart. She has been chosen, according to one envious colleague. With her selection, however, comes responsibility, so that the Sasquatch do not become exploited, whether by American intelligence interesting in using them as living weapons or by market tabloids and circuses. In fact, she is a bit indiscrete about who sees her drawings of her new acquaintances. Sometimes artists just can’t help themselves.

There is nothing cute here about the Sasquatch and their relationship to Lily, or about any of the forest animals we see in close-up (often followed by point-of-view shots) or in her portfolio. Animism, not Disney, characterizes this universe. Munch deserves buckets of credit: This is a hard act to pull off. Nothing is simplified either. In spite of her seeming at ease in what she wishes would be fully pioneer conditions, and no matter that she speaks with an almost arrogant cocksureness, Lily never really appears comfortable in her own skin. Her involuntary bouts of crying attest to some of what she’s masking.

Part of that is her recent break-up, to be sure, but there is an existential component: Like the Sasquatch, she is caught between two worlds. (We know nothing of her back story: Does she have family? Where is she from?) Her Forest Service boss is in bed with the feds, not only over the fate of the Sasquatch but also about the future of the huge protected preserves, where the agency determines who can log and how much they can move to market. On the other hand, the fling she has after a chance encounter on the trail with the very interested, sexy Sean (Jason Butler Harner), who has committed his life to dogmatic eco-friendly advocacy, makes her more sensitive to the strict demands of the environmentalists, even as she insists that “there are two sides to every story.”

Munch does not create division for the sake of dramatic momentum. He himself has pointed out that when the forests are not permitted their natural burning cycles, the overgrowth causes huge fires. A cynic might say that Sarah is unable to make up her mind about the way to proceed, or maybe that she is just fearful of taking a position.

The truth is that there is no contest for Sarah’s affection and attention between Sean and environmental politics, on the one hand,

and on the other, the Sasquatch. She recognizes that she has been blessed, and it only reinforces her intention since she lost her boyfriend to go it alone. She’s something of a cross between an Ayn Randian individualist, Johnny Weissmuller’s Tarzan, and a Leni Riefenstahlian heroine from her ‘30s mountain films (see blood and soil, above).

Sarah does have a few close pals on the hermetic forestry circuit, one a female Forest Service employee, Penny (Fiona Dourif), whom she considers her closest friend, the other a wildly bearded old logger, Barney (Jim Cody Williams), who has as much love for the trees as any preservationist. Along with Sean, they represent different vantage points from which to observe the marvels of the wilderness in tenuous coexistence with our civilization.

Try as she might, Sarah will never fully comprehend the various points of view about forestation, nor should she be expected to. Only the unglamourized Sasquatch, who make odd sounds in the night and sometimes lose it by banging tree trunks with branches, are equipped to fathom this fateful encounter. They do it in dark seclusion, not at antagonistic bureaucratic meetings or in the daylight wearing colorful outfits with all the right gear at hand.