Back to selection

Back to selection

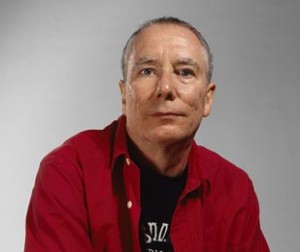

MIKE KELLEY, R.I.P.

Artist Mike Kelley, one of the most influential of his generation, died Tuesday at his home in Los Angeles. His provocative multi-media work mixed irony with sincerity, scatology with sentiment, and influenced not only other artists but filmmakers, musicians and writers. A founding member of the band Destroy All Monsters, he attended CalArts and collaborated with other artists like Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw and Sonic Youth.

Artist Mike Kelley, one of the most influential of his generation, died Tuesday at his home in Los Angeles. His provocative multi-media work mixed irony with sincerity, scatology with sentiment, and influenced not only other artists but filmmakers, musicians and writers. A founding member of the band Destroy All Monsters, he attended CalArts and collaborated with other artists like Tony Oursler, Jim Shaw and Sonic Youth.

From Holland Cotter’s New York Times appreciation:

He began creating multimedia installations that synthesized large-scale drawings and paintings, often incorporating his own writing, along with sculptures, videos (one was based on the television show “Captain Kangaroo”), and performances, often scatological and sadomasochistic in nature. Although he stopped performing in 1986 — he later said that he always had to get drunk to do it — the other formal elements remained constants in his art.

A certain tone or attitude remained constant, too. The shorthand term for it is abjection, a deliberate immersion in the gross-out anarchy associated with youth culture. But to see only that was to miss the deep and covered-up strain of poetry in his work, evident in a series of sculptural pieces using children’s stuffed animals sewn onto or covered over with hand-knitted afghans.

On one level, the pieces were sardonic send-ups of aesthetic trends like Minimalism, which Mr. Kelley despised as elitist. On another, they took aim at the strain of too-easy sentimentality he found repellent in popular culture. At yet another level, these pieces, with their martyred dolls and ruined promise of warmth, were innocence-and-experience metaphors, suggesting the trauma of hurt and loss that underlay the juvenile delinquent antics that surrounded them.

From Blake Gopnik’s piece in The Daily Beast:

“Protean” is the term that comes to mind for Kelley, if such a fancy-pants cliché weren’t so far from his aesthetic. “He brought a dialogue with real pop culture and everyday life into high art—that was untouchable before [him],” said Oursler. Kelley didn’t so much make fine art about popular culture, as Andy Warhol or Roy Lichtenstein had done, as erase the boundaries between the two.

Of course, some pop culture—especially the adolescent version of it that most fascinated Kelley—can have a nasty edge. My first review of a show by Kelley and Paul McCarthy, his frequent collaborator, described their “penile-anal-excremental videos and installations” as “laddish pranksterism.” What I wasn’t getting was that boys really do behave badly a good deal of the time, and that there ought to be art that takes that fact on.

Kelley made an especially strong mark in the 1980s and ’90s as a pioneer of what’s sometimes called the “art of the abject.” “He took things that were in everybody’s attics and made a picture of what it was like. No one had ever attempted that in any kind of metaphorical way,” said photographer and painter Marilyn Minter. Although seven years older than Kelley, Minter admitted that she wouldn’t have made her early “hard-core-porn paintings” without his example. Other, younger followers were much more direct, even derivative, presenting trash and junk and raw nastiness as their version of Kelleyan art. But as Sussman said, “Young artists might put a few things in a gallery, but [Kelley] would turn it into an epic project.”

Oursler said that from their very first meeting at Cal Arts he’d seen Kelley as the consummate poet: “Everything about him was tuned in to an aesthetic frequency—whether positive or negative.”

Below is video from Kelley’s Gagosian Gallery installation, “Exploded Fortress of Solitude.”

An interview with Kelley on his work and its relation to pop culture:

An an excerpt from his “Day is Done” performance at the Judson Church in 2009.