Back to selection

Back to selection

On Death at the New York Film Festival

At this year’s New York Film Festival I took part in a panel organized by Indiewire’s Critics Academy, a program for young, emerging film writers. The following is a consideration on the subject of death as it is depicted in three of this year’s films by one of those writers, Fariha Roisin. — SM

In Michael Haneke’s latest film, Amour, an opening wide shot captures a crowded mass. An audience is watching a piano recital, and we are hypnotized, unsure of where to look, or rather, who to look for. The shot gives us no clues and yet a romanticism lurks, suggesting that this act of watching live music has a certain universality to it, as does death and its true contender and antithesis — love. The camera finally focuses on Georges (Jean-Louis Trintignant) as he turns to Anne (Emmanuelle Riva) his wife. They are elderly, well-to-do. He watches her, silently captivated. There, his first act of amour is born.

In true Haneke fashion, the film unfolds slowly, bracing each shot with the director’s uncompromising style and realism. After the recital, Georges and Anne come home to find that their front door has been mishandled; all things point to an attempted robbery. Anne, shaken, says to Georges, “Imagine we’re in bed and someone breaks in.” He is blunt, unmoved by that hypothetical scenario: “Why should I imagine that?” The love that he maintains for Anne is unshakable: nothing can break — or will break — his ability to protect her. And as Anne begins to deteriorate from that point onwards — suffering a series of strokes that paralyze one side of her — her light begins to fade, and yet Georges proves that he is irrefutably dedicated to her.

To watch someone you care deeply for lose all cognition and vanish into nothing is a universal fear. Another film screening at this year’s New York Film Festival, First Cousin Once Removed, also details the horror such a loss of identity. Documentary filmmaker Alan Berliner showcases the life of Edwin Honig, the late poet, translator, critic and Berliner’s eponymous relation. Berliner documents Honig in the throes of advanced dementia as the years he spent collecting poems and memories all begin to collapse into nothingness. The inescapable question arises — what are we without our thoughts, our recollections? As with Anne, Edwin’s features begin to slacken, the understanding in his eyes begins to recede and any sign of life inside him begins to withdraw. To watch him deteriorate is a thrilling and yet emotionally draining insight into his world of debilitation. Like Edwin, Anne has lost all memory. But while Edwin is still somewhat functional, Anne has severely dispelled into a resounding slouch. Her eyes are clouds of opaque and she has a ghost-like presence that paralyzes each scene with her physical decay. When Georges spoon feeds Anne she is vastly losing her role as his wife and the roles are shifting exponentially. At a later feeding he pries open her mouth to force in liquid, but she refuses to drink it, spitting it out. His reaction — a slap — is a defense a parent would give to scold a child’s insolence. So, she is now the uncooperative child and he the frustrated father. Yet the love of Georges never wavers as for him amour means responsibility. Although once they led a blissful life, now he must embody the nurse, parent and bedside companion.

Family is a recurring motif of Haneke’s oeuvre, though unlike the sternness of his previous films, Amour is not submerged in mystery as we know what will happen in the end. No less terrifying and moving, it is instead an unmediated commentary on what love is. In Amour Haneke allows Riva and Trintignant a succession of small, tender moments that convincingly depict love, revealing it as the catalyst that drives us to selflessly protect those we fear losing. This inherent human tendency is itself a kind of trickery in that it enables us to believe we can deceive our sole inevitability — death.

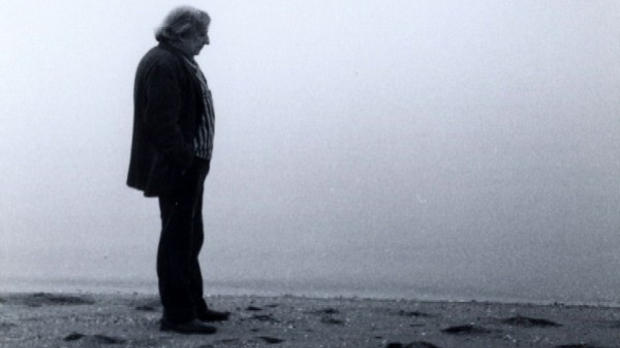

A third New York Film Festival film, Raul Ruiz’s Night Across the Street, is a surrealist depiction of the metaphorical contemplations of death. Released posthumously, in the vein of Fellini’s The Voice of the Moon and Cocteau’s Testament of Orpheus, Night Across the Street is no doubt a reflection on Ruiz’s own impending mortality. In a complex attempt to understand, or acquiesce to death, Ruiz fantastically critiques our melancholic fascination with the afterlife. With wordplay (“the night across the street”) and doubled meanings (towards the end of the film two shrunken men are in the barrel of a gun — the object that kills the protagonist — but also the passageway between life and death), he endeavors to reconcile this inevitable part of our human condition. Though profane, death is undoubtedly a transition to the next journey.

At the end of Amour, Georges tells Anne a story he has never told her before. When he was at summer camp, as a child, he would send a daily postcard to his mother. In order to get his true emotions, his mother asked him to draw flowers if he was happy and stars if he was unhappy. One day he wrote to her, the postcard covered in stars. As Georges finishes the story, he looks at Anne, a portrait of pain and unrecognizable uncertainty. He has already begun to mourn her and is ready to meet her again in the next passage, wherever that may be.

Death is only frightening because the physical faculties to appreciate friendship, music, literature, or even the people we love, disappear. Instead what is left is something unknown and completely removed from what we have learnt about ourselves and the world. Towards the end of First Cousin, Berliner asks Honig what advice he can pass on to the audience members that will watch this film. He doesn’t miss a beat: “Remember to forget.” Those words are loaded with meaning. Remember to forget carefully — to forget the pain, to forget the suffering and to forget this final act of deterioration. Berliner’s depiction of his mentor and first cousin once removed, is a way to commemorate his life, but also to document what he was, even in the last years of physical and mental degradation. In this requiem, Ruiz, Berliner and Haneke explore the institution of family and self, detailing, and perhaps coming to terms with, what will proceed after our inexorable demise, no doubt hoping, in whatever way they can, to create an enduring legacy that outlasts life, and love, itself — ever onwards to the journey that lies before us.

Fariha Roisin is a writer by day and a writer by night. A culture and film critic, she has a certain penchance for writing about women. Just recently she was a member of IndieWire’s Critics Academy, where she covered the New York Film Festival for both IndieWire and the Film Society.