Back to selection

Back to selection

Ken Burns, The Central Park Five

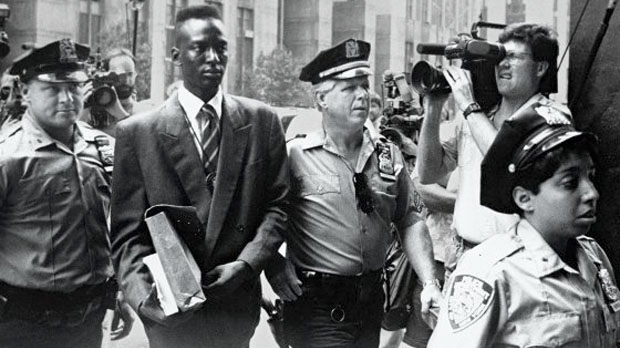

If you have a confession, then you have a conviction. At least that was the open-and-shut premise at the heart of the Central Park Jogger case, a crime story that inflamed racist paranoia in late ’80s New York City, stoking sensationalistic media coverage and frenzied outrage in the era of Bernard Goetz, Tawana Brawley, and the Bensonhurst murder, when the city was gripped with tensions that seemed ready to combust at any moment. After a white Wall Street banker from the Upper East Side was raped, beaten, and left for dead on April 19, 1989, while out for her nightly run in the park, police immediately rounded up a group of black and Hispanic teenagers from Harlem accused of “wilding,” a dubious term that denoted the terrorizing of random citizens by young hoodlums. Five boys, ages 14 to 16, were eventually charged with the assault—solely on the basis of their videotaped “confessions”—and sent to prison. Subsequent DNA evidence pointed to serial rapist Mathias Reyes, who confessed to the crime while behind bars at Rikers, and the convictions of the five young men were vacated in 2001, years after they’d completed their sentences. The Ed Koch-dubbed “crime of the century” had morphed into a story about an intolerable miscarriage of injustice, yet it barely registered in the news media.

In their new film The Central Park Five, which premiered at Cannes and screened this month at DOC NYC, filmmakers Ken Burns, his son-in-law Dave McMahon, and daughter Sarah Burns (whose 2011 book provided the basis for the film) untangle the weld of details—from questionable interrogation procedures and conflicting testimonies to the anger and hysteria fueled by police, prosecutors, city pols, and outrageously hostile news reports—that resulted in the wrongful convictions of Antron McCray, Kevin Richardson, Raymond Santana, Korey Wise, and Yusef Salaam. The latter four all appear on camera, recalling with anguish the events that led to their arrest, the grief and bewilderment of their families, and the aftermath of the case on their present lives. (McCray has changed his identity and agreed only to be interviewed by phone.) The filmmakers deconstruct the case with flawlessly logical precision and admirable patience for the tragic tale of each of the men it affected. Paired with the present-day interviews are judiciously interspersed sequences of (unnarrated) archive footage that evoke Gotham at its nadir in the ’80s, when urban decay, crime, and the blight of drugs would have made the pre-Giuliani city unrecognizable to today’s hipsters and bourgeois townhouse owners. Although police officials and prosecutors involved in the case were approached numerous times to appear in the film, they declined. Still, the City of New York recently issued a court order requesting the outtakes, hoping to dig for any detail that may help in its defense against a still-open lawsuit filed by the Five in 2003. “In large part,” says Burns, whose company Florentine Films filed a motion to quash the subpoena, closure remains elusive for the city “because they can’t answer the questions that this case, to a large extent, demands that they answer.”

Filmmaker spoke with Burns about race and national memory, New York City in the ’80s, and why documentary is more creatively engaged than ever. The Central Park Five opens Friday in New York.

Filmmaker: As a filmmaker with an audience in the millions, do you sometimes feel like an unofficial custodian of national history?

Burns: Not at all. That would be so arrogant and presumptuous. What I want to do is tell good stories and as it happens my personal interest is in American history. These stories have been wide and diverse, and though I understand that tens of millions watch them whenever they’re out, and that they often have a powerful effect because of the number of people they reach, I wouldn’t presume to think either that I was making a definitive film about baseball or the Civil War or that I’m responsible for national memory about a particular subject.

Filmmaker: You’re often engaged in unpacking periods of history, such as in your upcoming series The Dust Bowl, or profiling individuals. The Central Park Five is event specific. How did handling a story that unfolds on a smaller scale, though it clearly has a wider resonance, work out for you?

Burns: The wider resonance is what drew me to it. My daughter had been investigating [the case] and was writing a book, and I had the privilege of seeing her early drafts. Within a few pages I realized that this fit entirely with the kind of work I’ve been interested in—it seemed perfect. And what this afforded me, working my daughter and my son-in-law, the extraordinary filmmaker David McMahon, was a chance to stylistically invigorate the telling of this story. As you see, there’s no narration, unlike other films I’ve made, and it’s shorter than the others, leaving open the possibility of a theatrical run. At the same time, it permitted me to explore themes I’ve been exploring the past 35 years: justice and the meaning of American identity.

Filmmaker: The history of race relations is certainly embedded in this film, too.

Burns: In so many films, like Jazz or Baseball, we pass through the Jim Crow era, and the horrific language of that is mirrored in the press [on this case]. Instead of being skeptical and questioning, [they] fully accepted the police and prosecutors’ version of the events and helped set in motion a feeding frenzy that then began to emulate not the language of a progressive city in the 20th century, but the lynching language of Jim Crow in the late 19th/early 20th century.

Filmmaker: Was the decision to leave out narration and complete the film in a shorter time frame primarily related to getting The Central Park Five a theatrical release?

Burns: What’s always important is how to tell the best possible story. It was very clear, almost from the beginning, that this was a story that could almost tell itself. Because it was about a specific event, and not an era or an individual that would need the more traditional framing that narration does. In its place, in this film, is very spare information given by interstitial title cards. Like in any film, the pace and rhythm are often determined by the music of the time. If you think of the chaos and terror of New York in the ’80s, coupled with the birth of hip hop, you’ve got not just a historical rationale, but almost an artistic imperative, at least initially. At other times, the film settles down into slower rhythms to permit the audience to experience the unknowing and fear that was probably a huge part of the experience of the Five as they were being interrogated alone for so many hours and then finally, of course, to summarize their coerced confessions in the videotapes. Those sequences are still excruciating for me to watch.

Filmmaker: Most viewers I saw the film with found them enraging.

Burns: Yes, enraging. One thinks about subsequent structural considerations—the trials, the incarceration, the paroling, the exoneration and denouement—all of that has a pace which leads, I believe, to further outrage.

Filmmaker: Which of the Five did you get closest to first?

Burns: That’s a much better question for my daughter Sarah. She’s known most of them since 2003, and she and Dave did most of those interviews for the film, and I did the others with the journalists, mayors, and defense attorneys. Subsequent to the film, I developed a relationship with everyone but Antron because he’s changed his name and settled into a house and wishes to remain anonymous. He has a job and children and he’s trying to protect himself from that great terror again. I’ve spent more time with Raymond because he’s accompanied me to more of the film festivals, but I’m not any less close to Korey, Kevin, or Yusef. They are all extraordinary people filled with such forbearance and a wisdom you would expect with someone twice their age, and a noticeable lack of any real bitterness. They’re resigned to the fact that the forces arrayed against them are powerful, well-funded, and hoping to outlast them. We hope our film is part of this transformation, but the name “the Central Park Five” originally invited the world’s scorn and has now become something in limbo. One hopes [that term] represents people who withstood the system and have come out [the other side], and that to be a member of the Central Park Five is to be part of a heroic band of brothers.

Filmmaker: Is that how they see themselves?

Burns: You know, they didn’t know each other before that night, and the sad thing is all the hoopla surrounding the actual crime and their charging was not matched when they were exonerated, which permitted the reactionary forces within the police department and the prosecutors’ office to spend the last decade offering absurd counternarratives that do nothing but delay justice. And justice delayed is justice denied, and we’ve already been through that the previous 13 years.

Filmmaker: The City of New York recently filed a court order to seize your notes and footage from the film, which shows just how open the wound still is.

Burns: Yeah. We’re in no way representing the Five, nor are we representing their suit against the city. We just recognize that as filmmakers and citizens, closure in this case serves not only the Five and their families, but the city and the rest of us. Mayor Ed Koch called it “the crime of the century.” By delaying all we do is permit this crime and the divisions that are suggested by this miscarriage to fester. Closure seems to be what most intelligent people—whether they agree on motives or circumstances or not—seem to feel would be the best thing. But unfortunately there are reactionary forces in the city whose interest it is to delay as much as they can.

Filmmaker: How does it change things for you when you’re dealing with living subjects and in effect influencing history as it’s being written?

Burns: Well, I hope we’re not influencing history—we want the film to provoke interest in people so that perhaps the case could be settled. But we don’t want in any way to dictate the terms of that settlement nor do we wish to be perceived as representing the Five and their lawyers and their brief as opposed to just being journalists in an objective sense. It’s different and also the same. The demands of storytelling require you to accept the limitations of the moment—I can’t interview Abraham Lincoln for my Civil War series, as much as I’d like to, nor do I have any motion picture of the Civil War, as much as I’d like to have that, so I have to make do with having someone read his words and using the still photographs, none of which themselves show any pictures of battle. It’s always the horror after. So you take a bit of poetic license. When someone’s around, you have the great gift of access to them, but perhaps limitations in other ways. Ironically, Lincoln said it best when he was forced to reinstate General McClellan. He said, “We have to use the tools we have.”

Filmmaker: Apart from the story of the justice system and the five individuals who were wronged by it, we really feel the grit of New York City in the eighties in The Central Park Five.

Burns: It’s something Sarah, Dave, and I felt unanimously we had to do. A real character in the film is the City of New York at that time, both its racial dynamics and its atmosphere of police enforcement, or lack thereof, the decay of the infrastructure, the pall of crack cocaine, the financial crisis and its fallout, the great divide between the haves and the havenots. Part of why people swallowed this improbable tale of “wilding” teenagers rather than a sociopathic rapist whose M.O. was all over that crime and many others was that it fed everyone’s spoken and unspoken fears. And it’s funny we were able to make these five the ultimate boogeymen when in fact real detective work would have uncovered instantaneously the real culprit. In fact, they should have had him two days before when an assault on a woman was broken up and she was able to give a description and they were able to know who it was and never followed through. That is still an outrageous crime that permitted the assault on Trisha Mieli to take place, plus subsequent assaults including the murder of a pregnant woman. Still no one was able to walk the DNA over to the boys’ case. We wouldn’t be talking about this if someone—anyone—had entertained another scenario. Clearly, this represents detective work at its worst, and prosecutorial misconduct at the very least.

Filmmaker: It’s interesting that so many documentary filmmakers in the past three decades since The Thin Blue Line have devoted themselves to exculpatory work and made themselves experts in legal affairs.

Burns: Well, I don’t think it’s conscious, as much as it might seem—there must be ten films on the West Memphis Three. What I think the traditional role of documentary—and it certainly hasn’t been my role, I’ve been interested in a deeper dive in history—but one of the roles has been to be a contemporary social conscience. One thinks of CBS Reports, the landmark Harvest of Shame, pointing out the conditions of migrant workers, and the continuing tradition of 60 Minutes and its investigative work. What I think happens is that being keenly aware of the injustices of the moment more often than not focuses on the unusual number of minorities who’ve been put in jail for crimes they haven’t committed. That becomes what’s in the purview of the documentary community. In this case, the press so bought the story hook, line, and sinker, it becomes the responsibility of us later. I still think of this film as history, as recent history. Our film doesn’t detail a period but happens between two mileposts: April 19, 1989, when the crime took place, and December 19, 2002, when Judge Tejada vacated [the] convictions.

Filmmaker: How did you first approach film as narrative?

Burns: I went to Hampshire College in 1971, in the second year of its existence, and I concentrated solely in film and photography, and particularly film production and design. While I didn’t go to a formal film school, per se, ninety percent of my undergraduate education was focused on filmmaking. I had wanted to be a filmmaker since I was 12 years old—I had initially wanted to be a narrative filmmaker, and I was taught at Hampshire by Jerome Liebling and Elaine May and social documentary still photographers who reminded me that there’s as much drama in what is and what was than anything the human imagination makes up. So I was committed to becoming a documentary filmmaker, unaware that I would join that passion with my own internal, untrained passion for American history. I understood early on that the same laws of storytelling applied to documentary as well as narrative features. The dynamics are the same—and that’s something new. For a long time I think documentaries were didactic, they were essayistic, they were propagandistic, telling you what you should know—they did not subscribe to the laws of narrative in the same way that they do now, in recent years. That’s helped elevate documentary onto a parity with [fiction] films. Feature films in Hollywood are tired—it’s the same old [thin] plot with ever more spectacular bells and whistles. What seems so fresh in documentary now is that each is following the same laws of storytelling that Steven Spielberg has to follow. My friend Werner Herzog does more documentaries than [narrative] films; he’s engaged in passionate, operatic, ecstatic documentaries that are a wonderful revelation and couldn’t be more different from mine. Night and day. At the same time, I recognize them as the great works of art they are. But each life experience is unique, and that’s why I think documentary has moved to the fore.