Back to selection

Back to selection

BILL GUNN SURFACES AT BAM

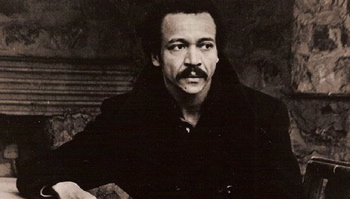

You could say that Bill Gunn was a man who came before his time, but that leaves you working under the flimsy assumption that a time more hospitable to this man of undeniable talents and mercurial preoccupations would some day come. If you don’t already know this is a weak proposition, you’re not paying attention to the tenor of the times we live in. One can be forgiven for being unable to relate to the struggles of an unorthodox black artist to find proper patrons and an appreciative audience I suppose. Still, it is better to say that Bill Gunn, the African-American actor, director, screenwriter, and playwright who died from encephalitis on April 5th, 1989, just one day before Joseph Papp opened Gunn’s new play The Forbidden City at the Public Theater, was a man with a vision we were never quite ready for, black or white, studios or independents, 1970 or 2010. He just didn’t fit the equation of black writer/director = realist/earnest, racialized subject matter that the comers of his generation, especially his peers among Hollywood’s first black directors, Ossie Davis, Gordon Parks and Melvin Van Peebles, very willingly molded themselves into. No wonder then that the author Greg Tate, while eulogizing this unclassifiable man in a 1989 piece for The Village Voice shortly after Gunn died at 59 (or 54, depending on who you talk to), his couple of near masterpieces long forgotten, so aptly observed that “The attempt to bury Bill Gunn began in his life.” While his work on the New York stage spanned from roles in 1950s Broadway and Off-Broadway shows like The Immoralist and Take a Giant Step to his dying days, in his all too short and undervalued career as a director and screenwriter, we hardly got to know him. This weekend, BAM is offering us a second chance.

You could say that Bill Gunn was a man who came before his time, but that leaves you working under the flimsy assumption that a time more hospitable to this man of undeniable talents and mercurial preoccupations would some day come. If you don’t already know this is a weak proposition, you’re not paying attention to the tenor of the times we live in. One can be forgiven for being unable to relate to the struggles of an unorthodox black artist to find proper patrons and an appreciative audience I suppose. Still, it is better to say that Bill Gunn, the African-American actor, director, screenwriter, and playwright who died from encephalitis on April 5th, 1989, just one day before Joseph Papp opened Gunn’s new play The Forbidden City at the Public Theater, was a man with a vision we were never quite ready for, black or white, studios or independents, 1970 or 2010. He just didn’t fit the equation of black writer/director = realist/earnest, racialized subject matter that the comers of his generation, especially his peers among Hollywood’s first black directors, Ossie Davis, Gordon Parks and Melvin Van Peebles, very willingly molded themselves into. No wonder then that the author Greg Tate, while eulogizing this unclassifiable man in a 1989 piece for The Village Voice shortly after Gunn died at 59 (or 54, depending on who you talk to), his couple of near masterpieces long forgotten, so aptly observed that “The attempt to bury Bill Gunn began in his life.” While his work on the New York stage spanned from roles in 1950s Broadway and Off-Broadway shows like The Immoralist and Take a Giant Step to his dying days, in his all too short and undervalued career as a director and screenwriter, we hardly got to know him. This weekend, BAM is offering us a second chance.

In the series The Groundbreaking Bill Gunn, which begins tomorrow and runs through Sunday, one can get a glimpse at both of Gunn’s studio screenwriting credits (Hal Ashby’s remarkable Brooklyn gentrification comedy The Landlord and Czech New Wave stalwart Jan Kadar’s first American feature The Angel Levine, both from 1970), and his best known work, 1973’s Ganja & Hess. A bona fide cult film, it is the anti-Blacula, defiantly difficult and parochial, a vampire film in which the word itself is never used and its tropes mostly discarded. Shot in honey dipped 16mm, the film is a lyrical and melancholy menage a trois with no less than the Protestant God as its deux ex machina and Gunn himself as a suicidal anthropologist’s assistant with a penchant for monologue. As utterly unclassifiable as its auteur, Ganja & Hess is both deliberately austere and thematically potent. Gunn subversively deconstructs the class relations that exist within the black “community” and the expectations of both his financiers and his potential audience while delivering a meditative and un-condescending representation of black protestant Christianity within a potentially lurid black exploitation movie, one which was the toast of the 1973 Cannes Film Festival’s Critic’s Week before it was radically recut by its distributors into a sexploitation film and boxed up under six different titles in the early days of VHS.

The real coup of BAM associate curator Jacob Perlin’s program is the unearthing of a pair of Gunn’s even more obscure film works. The program opens tomorrow with the Harlem set, “experimental soap opera” Personal Problems from 1980, which Gunn conceived with the novelist Ishmael Reed, who also published Gunn’s 1981 autobiographical novel Rhinestone Sharecropping under his “I Reed Books” imprint. Even rarer is Gunn’s Warner Brothers’ financed directorial debut Stop! from 1970, a formally radical chamber piece which centers on a New England poet and his wife as their marriage disintegrates during a vacation to San Juan. After a brazen, hotel room infidelity, the bored bourgeois protagonists hardly have time to discuss their collapsing bond before they encounter another couple with whom they are familiar with in the sun drenched resort town. Very quickly, all four begin to unambiguously seek their desires (and take out revenge upon each other) in an increasingly high stakes series of sexual entanglements that stop at nothing short of emotional hostage taking. Perhaps the first studio financed film to clearly and emphatically represent homosexual and interracial sexual contact in the midsts of a narrative that gradually drifts toward the surreal and quietly depraved, I got the impression that The French Connection’s Oscar winning DP Owen Roizman did amazing work on the film, but one may never really know: after it was inexplicably greenlit just a year after Warners made Gordon Parks the first black studio director with his autobiographical The Learning Tree in 1969, the studio permanently shelved Stop! Although it has never received a commercial release, the only existent 35mm print was revived by the Whitney at a retrospective of Gunn’s work following his death. It disappeared into Warner vaults twenty years ago and the studio now claims they don’t have it. A VHS copy unearthed by co-star Jack Hoffmeister will screen for free on Easter Sunday.