Back to selection

Back to selection

Top Riders: New Directors/New Films

The Act of Killing

The Act of Killing It’s my favorite time of the New York movie year: the New Directors/New Films festival (March 20-31), now in its 42nd edition. A New Directors film may be artful, heady, provocative, or innovative — or all four. Not always super polished — that’s traditionally more up the New York Film Festival’s alley — it should indicate promise. To that end, this crop pretty much delivers.

A number of selections favor a bit of fakery in lieu of naturalism in order to get at some sense of truth. Just as you can make a case for the greater honesty of Méliès’s magic films compared to the Lumière brothers’ “actualités,” new features like The Color of the Chameleon, The Act of Killing, Rengaine and The Shine of Day add to the ongoing blurring of artifice and reality.

The interior journey of a principal character is the common denominator among other films. They run the gamut: involuntarily adventurous teens in Blue Caprice and They’ll Come Back, a beaten-down old man in Kuf.

Below I elaborate on the seven titles (in no particular order) that for me are the strongest among the first week’s screenings. In the week ahead I’ll do the same for the second batch.

“You look like an angel

Walk like an angel

Talk like an angel

But I got wise

You’re the devil in disguise”

“Devil in Disguise,” lyrics: C. Hillman, G. Parsons

The Color of the Chameleon (Emil Christov, Bulgaria)

In Bulgaria, young, handsome Batko (pop singer Ruscen Videnliev) adapts to the fall of Communism and its replacement with “democracy” by morphing from straight-laced geek into slick opportunist. He alters not only his appearance but his overall persona, always coming out ahead.

This highly original film begins during Batko’s adolescence. His aunt complains to a government official about the boy’s compulsive masturbation. The intentionally overplayed scene is a prelude to a recurring comic connection between sex and state; onanism is a leitmotif. The absurdity of that scene sets the tone for this successfully satirical movie.

A few years later, near the tail-end of the Communist era, Batko is recruited by state security to infiltrate an organization of intellectuals. They belong to the Club for New Thinking, the members of which intensely study a book called Zincograph (also the title of the novel adapted for the screen by author Vladislav Todorov), which includes a character who creates a fictional network of subversives who run circles around the secret police. He gets fired. In the course of wonderfully ludicrous events, he transforms himself from blindly obedient slave to the spying apparatus into fast-talking trickster operating his own espionage set-up, one in which Groucho Marx and Peter Sellers would feel at home.

The crisp, sometimes fanciful cinematography and terrific, poker-faced acting (not LOL) keep the film from straying too far from any recognizable reality. It is chock full of visual gags, lighthearted references to cinema, and engaging, over-the-top supporting characters. Irreverent across the board, it pokes fun at both apparatchiks and free-thinking radicals.

The Act of Killing (Joshua Oppenheimer, Denmark)

Oppenheimer is a Texan living in Copenhagen. The funding for this extraordinary “documentary of the imagination,” as he calls it, came from academia. He explains that he was not subject to many of the restraints other docmakers have to endure. “Imagination” here means kitsch and theatricality.

Oppenheimer convinced a group of Indonesian gangsters to reenact their parts, and sometimes the role of victim, in the torture and execution of one million leftists, ethnic Chinese, and intellectuals in 1965, just after a U.S.-sanctioned military takeover. These gangsters (who argue way too much about the word’s translation as “free men”) belong to a paramilitary group called Pancasila Youth, one of several that had been given free rein by the right-wing government. It is still hugely popular, and counts top politicians among its supporters.

Film is ideal for deconstructing this relatively unknown genocide. As young men, the gangsters were merely petty criminals who sold movie tickets on the black market, and who used local cinemas as their bases. Oppenheimer asked them to use genre — westerns, musicals, gangster movies, etc. — as the cornerstone of their staged testimony.

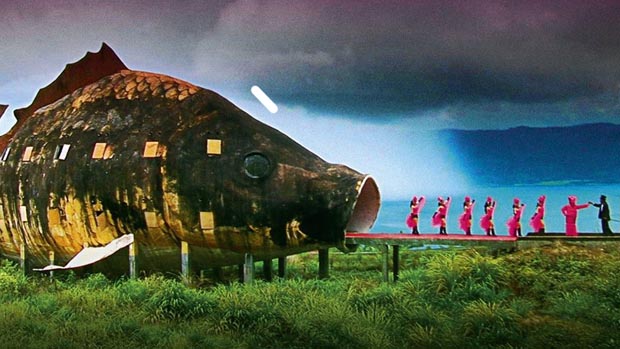

Flamboyant Anwar Congo is the thread linking different sections of the film, from displays of strangulation by wire (bloodless, it became the favored method of killing) to the massacre of an entire village to outrageous contemporary fantasy sequences (see image above), rehearsals, and ordinary banter. Most of the men have channeled potential regret into light diversions, keeping themselves entertained, but the presence of Congo, the most troubled of the lot, adds an almost Shakespearean tragedy about one man to the horrific collective one from 50 years back.

Rengaine (Rachid Djaidani, France)

Djaidani is a novelist, but, based on the evidence of this first feature, you might think he is a veteran of the plastic arts. With gusto, he films this interracial, interreligious love story (the title translates as Refrain, but Hold Back is also used) with a small handheld camera, capturing the energy among the second generation of Maghrebian and sub-Saharan immigrants in a rundown section of Paris. The tension between dogmatic tradition and less restrictive attitudes contains the otherwise aimless chaos.

Sabrina (Sabrina Hamina) is the only daughter in an extended Arab Muslim clan. Slimane (Slimane Dazi), the eldest of her 40 “brothers,” takes it upon himself to speak to each of the others to harness their opposition to her impending marriage to the soft-spoken Dorcy (Stephane Soo Mongo), a black Christian of Malian descent. Romeo and Juliet and West Side Story both come to mind. That Dorcy is an aspiring actor with few prospects is not an issue; his make-up is.

The characters are frequently photographed in close-ups that mask the backdrops which would normally define a setting. We see grafitti, decaying facades, and dank interiors, but Djaidani never lets us lose sight of these people. The brothers have internalized, centuries-old prejudices; Sabrina basks in the freedom she finds in Europe. In fact, the few women here, like the director of a film-within-the-film, are headstrong, willful. Not to give anything away, but the exposure of hypocrisy and a lesson in the power of love and hate that hits close to home undermine any expected course of events.

The Shine of Day (Tizza Covi, Rainer Frimmel, Austria)

Unlike many of the selections in ND/NF, this film is formally conventional, a smooth, well-made cousin of the TV movies that proliferate across Europe. Yet it has a different kind of magic. Bordering on chamber play, it features two principals whose proficient acting is complementary. That their characters engage in the same professions and occupy similar cultural niches as the actors who portray them might account for some of that power.

They also retain their real names. Philipp (Philipp Hochmair) is a well-known theater actor based in Vienna. Walter (Walter Saabel) is the step-uncle he never knew, a circus performer who once wrestled with bears. Walter arrives unannounced on Philipp’s doorstep. He ends up staying with his nephew — and staying. The two have little to talk about, but gradually they find points in common.

Both are exhibitionists (Philipp frequently struts around in costume), as most performers are, but in different ways. Each takes an interest in the working-class family next door — Austrian father, absent Moldavian mother, and two adorable children — looking out for their welfare.

The title refers to those special moments we experience that occupy the space between ecstasy and epiphany. For both Philipp and Walter, the “shine of day” relates to an abstract concept that they both embrace: “living free.” One man’s freedom is another man’s prison, of course, and the film plays nicely with the distinction.

“Leaving the world behind

We travel on through silence

With only the stars to guide us

Along the lonesome trail”

“Lonesome Trail,” lyrics: Chris Squire

Blue Caprice (Alexandre Moors, U.S.)

For a film about the 2002 sniping rampage by John Allen Muhammed and protégé Lee Malvo, a very well-known media story, the narrative proportions are “so” right. The opening sequences in laid-back Antigua are relatively placid — until 40-year-old vacationing American John (Isaiah Washington) rescues abandoned 17-year-old island resident Lee (Tequan Richmond) from suicide by drowning.

Once John takes Lee back home to Tacoma, Moors fills in John’s backstory. Except for loud and raucous shooting practice and the killing of one of his father’s old nemeses by the newly programmed Lee, this extended section moves fluidly. The two spend time in the rundown house of one of John’s old Army buddies (Tim Blake Nelson), his slutty wife (Joey Lauren Adams, fabulous), and their baby. They run errands. John begins to harshly discipline Lee, and we observe the former as his unfocused rage surfaces incrementally. He concocts a scheme: For starters, the two set up a firing station inside the used car of the title.

This title makes perfect sense once the men hit the road and drive to the Washington D.C. area. Scenes of the killings, with Lee aiming his rifle through a hole in the trunk, serve as the shots in classic shot-reverse shot set-ups. And symmetrical scenes of the car, gliding smoothly along the highway, act as the reverse shots normally reserved for human characters. The depiction of the horrifying murders, each filmed differently but all very rapidly, keeps the element of surprise intact. Victims include a woman who blithely enters the frame and bumps into an expectant mother we have been watching, and a senior walking alone in a supermarket parking lot.

We all know how it ends. Moors shakes things up by focusing on Lee’s obliviousness, the amorality that guided a student who learned too well.

Kuf (Ali Aydin, Turkey)

Like many Turkish films that get around the arthouse and festival circuits, Kuf (it translates as Mold, hardly a blockbuster title in English) takes its time telling a story: long, long takes, no camera movement, tight compositions. It’s more about characters and landscape than plot. The protagonist, elderly Basri (an astonishing performance by Ercan Kesal), is as dull and lethargic as they come. His job is boring, redundant: He walks the railroad tracks checking for problems around the provincial Anatolian town in which he lives. He is so enervated that he barely answers when someone asks him a question, standing as if mesmerized during an uncomfortable lull.

The man has his reasons. Eighteen years before, his son disappeared during student uprisings in Istanbul. His wife died shortly after, presumably a suicide. The only thing that structures Basri’s day is writing letters, over and over again, asking the authorities for information about his son. The obsession has become a local joke, but the search is his sole motivation for living.

Breaking the monotony of this character are two others, a polished, aloof railroad head and a vulgar, offensive maintenance worker who taunts Basri. Both are stereotypes, perhaps intentionally, the better to maintain interest in the old man. In fact, the institutional settings that appear in the latter part of the film threaten to overpower him.

The countryside here is different from other Turkish films we’ve seen. Instead of breathtaking, verdant mountainsides and tall trees, we get pebbles, rock formations, rail cars, and endless metal tracks. There are some more typical scenes of nature at its most lush, but they are few and far between.

They’ll Come Back (Marcelo Lordello, Brazil)

The film is set along a remote northern Brazilian highway and its small offshoots that lead to disparate places: poor squatters’ villages or the beach homes of the moneyed from Recife. The flip side of a road movie, this coming-of-age story explores the internal life of 12-year-old Cris (Maria Luiza Tavares, underplaying splendidly), who wanders these routes after her rich parents inexplicably abandon her and her teen brother on a shoulder of the highway.

What we find out about the mother and father might have made for stronger drama, but the observation of Cris’s subtle transformation is more profound and satisfying — especially in a rapidly developing country with such an enormous gap between rich and poor.

In the hands of director Lordello and talented d.p. Ivo Lopes Araujo, the film never lets us lose sight of Cris, often against the flat landscape along the main road, interrupted only by sporadic shots of the ocean and domestic interiors. After she and her brother lose each other, she accepts the invitation of a young indigenous boy to go to his modest home and eat. His mother and sister feed and take in this, as they say, “very white” girl.

To his credit, Lordello neither ennobles nor demonizes the locals. The mother and another woman who allow Cris to stay make clear that they can not keep her long, that they can not provide for her, so her fate is decided by consensus at a meeting of village adults. The local police are powerless to help her, but she manages to find her own way between local hospitality and the discovery of more familiar turf, the expensive second homes of the privileged.

Back in Recife, she makes comments and engages in heretofore forbidden activities that might lead us to believe she has become a more open thinker, but Lordello does not offer easy closure. The ending is appropriately ambiguous: We have to invent our own answers.