Back to selection

Back to selection

Cannes 2013: Portraits of Purgatory

The Great Beauty

The Great Beauty Portraits of purgatory dot this year’s Cannes Film Festival, with movies that run the gamut in terms of styles and techniques: epic drama, cheeky comedy, documentary, animation, and surrealism. No matter what the setting, the plight is the same, with characters stuck in a cycle of emotional limbo where hope for happiness floats tantalizingly but incessantly out of reach.

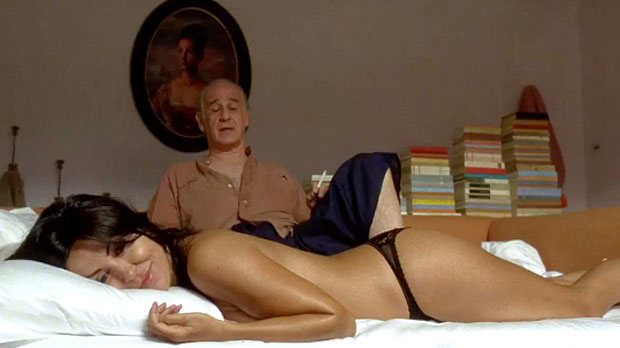

The most accomplished of the group is The Great Beauty, Paolo Sorrentino’s voluptuously crafted riff on La Dolce Vita and a masterful study of 65-year-old Jep Gambardella (Toni Servillo), a dilettante journalist still coasting on the acclaim of a single early-career novella, who has devoted his life to highbrow debauchery instead of literary craftsmanship. His home is Rome, his apartment a veritable den of iniquity where he hosts all-night parties on an enormous terrace overlooking the Colosseum. His world consists of attending empty performance art pieces, hobnobbing with shallow glitterati, and endlessly dining at the best restaurants in town. But he is haunted by the recent passing of his first, long-lost love, whom he now discovers always carried a torch for him despite her ending their affair.

Her death sets in motion a sequence of soul-searching events that culminate in the appearance of Sister Maria, a Mother Teresa figure whose piety climaxes Jep’s spiritual upheaval. And the restless ennui that Jep exudes is wrought with a beguiling mix of humor and heartache; Sorrentino’s restless camerawork and sumptuous cinematography depict a world of tantalizing excess that’s equal parts heaven and hell.

The Bling Ring is its own special purgatorial vanity fair, a surface-thin bauble about surface-thin people who traffic in image-ready booty stolen from the houses of tabloid celebrities. Sofia Coppola’s hollow exposé is an intriguing study of empty lives desperately filled with the cribbed jewels and couture clothing of the rich and famous. Style equals content, damn the consequences, while life is an endless cycle of petty thefts and titillating robberies. The vapid life cycle is its own reward and damnation, and there’s a palpable sense that no redemption or punishment will ever change their bad behavior.

James Toback and Alec Baldwin’s film-finance lark, Seduced and Abandoned (shot here in Cannes during last year’s festival), turns a lively if self-pitying documentarian’s eye on the Sisyphean task of finding the money to make a movie. Filmmakers such as Francis Ford Coppola, Bernardo Bertolucci, Roman Polanski, and Martin Scorsese all share quick anecdotes in which they bemoan the endless fights and constant finagling they have to endure to get another picture made. And mighty producers and studio chiefs, including Jeffrey Katzenberg, Mike Medavoy and Avi Lerner, talk briefly about the sea changes in production funds and quickly illuminate the market pressures that force human dramas into the shadows while tentpole blockbusters get pole positions. Nothing ever goes deep in this quip-filled exercise in wound-licking, but many charming people get to say no repeatedly to Toback, who quixotically keeps asking people for money to make a sex-charged two-hander set in Iraq, which he pretentiously refers to as Last Tango in Tikrit. The endless hope for another chance to make a great movie drives all these souls — though viewers will leave with the impression that Toback gleefully exudes a morbid sense of futility towards the whole exercise.

One of the most poetic renderings of lost souls here at the festival is The Congress, Ari Folman’s admirably flawed, deeply trippy and very loose adaptation of Stanislaw Lem’s sci-fi novel about a world in which celebrity-steeped illusions are the opiate of the masses. Robin Wright plays a washed-up version of herself who sells her digital likeness and “performance rights” to a studio sick of dealing with the indiscretions and demands of countless unreliable actors. Fast-forward 20 years, and Wright, after inhaling a hallucinogenic gas, checks into a remote luxury resort and finds herself in the midst of a revolution against a giant entertainment/pharmaceutical conglomerate which wants to buy her biological essence and sell it to a public hungry for distraction. Folman’s ambitions ultimately sabotage the panoply of arresting ideas and themes; and while it doesn’t completely gel, the film’s depiction of metaphysical uncertainty definitely lingers.

Purgatory couldn’t get a more moving depiction than in Alejandro Jodorowsky’s autobiographical fantasia, The Dance of Reality. Revisiting the travails of his childhood, the Chilean director uses his longtime surrealist outlook to capture the sense of helplessness he felt as a child living with a tyrannical father (played, ironically, by Jodorowsky’s own son, Brontis). Circus clowns, angry mobs of amputees, a mother who only talks in an operatic singsong, and a costume-loving dwarf tubthumping for customers outside the father’s clothing store are but a few of the feverish images that populate this Latin American Amarcord. But Jodorowsky’s memory piece deepens as it follows the father’s transformation from monster into martyr, and ultimately allows for the characters to find an escape from the suffocation of their country’s political turmoil. Cannes dependably offers visions of perpetual malaise, but, in the right hands, the best ones always become odes to joy.