Back to selection

Back to selection

Park City Critic’s Notes #1: Jungle Violence and Prairie Reckonings

Concerning Violence

Concerning Violence Generally speaking, the documentary competitions sections of major market film festivals are not places to go and find uplift. Wanna feel good in, say, the James Brown sense of the phrase? The Premieres or Spotlight sections at a festival such as Sundance are usually better bets, programs that tend to provide, with some notable exceptions, a bevy of of biopics, inspiring tales and quirky comedies packaged to appeal to vain movie stars and whatever audience still remains for mid-to-lowbrow, adult-centered specialty films. Any world where the people are all as attractive as, say, Keira Knightley, Chloë Grace Moretz and Mark Webber, as in one Premieres title this year, can’t be all that bad. But at Sundance, in the Doc competitions, especially the World Documentary Competition, one can find some particularly harrowing visions of what went on, and is going on, out there.

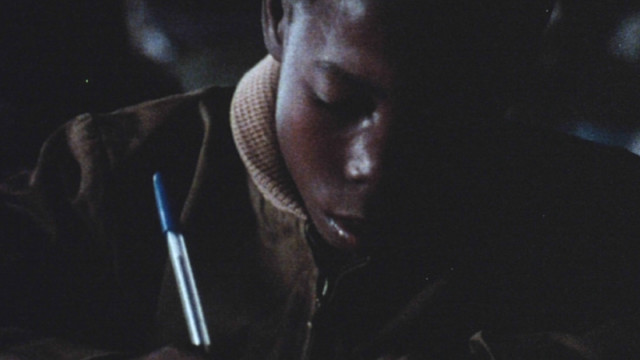

The various liberative movements that led to the sovereignty of much of sub-Saharan Africa in a swath of uprisings during the 1960s rarely get the historical hubbub the American civil rights movement does, but Göran Hugo Olsson’s Concerning Violence might prove a temporary corrective to this state of affairs. Using a similar, all-archival, heavy-on-voiceover style as his previous Sundance World Documentary Competition outing, 2011’s The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975, Olsson uses found footage from various European TV outlets to erect nine elliptical narratives of nationalistic struggle for self-determination in the age when all of Europe’s old colonial powers began to retreat from the last outposts of their faded empires. Newly released from jail, Lauryn Hill narrates rhetorical interludes drawn from Franz Fanon’s classic work of psychiatric analysis that takes on the dehumanizing effects of colonization on the Colored mind, The Wretched of the Earth, a book this film claims much inspiration from, although to call it an adaptation, as it does in its credits, might be something of a stretch.

Concerning Violence, which contains chapters meditating upon Zimbabwe, Guinea, Mozambique, Congo, and South Africa, among other theaters of colonial strife, treats us to a plethora extraordinary moment . We glimpse a still young, still seemingly sane Robert Mugabe talking about redistribution of land; we visit Portuguese platoons in Mozambique caught in the fog of a jungle war with guerrillas who have nothing to lose; and we get searing interviews with white settlers who still can’t bring themselves to relinquish their narrative of racial superiority even as they fear being killed when the countries they and their countrymen have long exploited rapidly free themselves from such tomfoolery. The film showcases, in the gentle verite that came so readily to news cameramen of the era, the stark differences between the chic compounds of the ex-pats and their flocks versus the unadorned, communal settlements of the natives while it also delicately observes the alienating tension that these circumstances bequeathed on individuals black and white. It’s a propulsive, hypnotic experience, despite the social-political enormity of the subject; Olsson has asserted himself as the most kinetic of the vanguard found footage artists who have emerged on the international documentary scene in the past few years.

Like Fanon’s text, Concerning Violence makes a stark point: Negroes, both in Africa and, to a lesser degree, in the West, had to use violence, or at least the threat of violence, to free themselves, despite their power in numbers (one white landowner in Zimbabwe, who openly, while being filmed, humiliates his black servants, claiming he won’t leave as the country’s political apparatus is taken over by Blacks, spends the rest of his time bemoaning how much of a lost cause it is for whites to stay in these places when they’re outnumbered 20 to 1). Talk all you want about the Ghandian tactics of the main line, liberal integrationist strand of the CRM, but without the threat of armed insurrection from Black nationalists, these movements wouldn’t have borne any of the two sided fruit, both legislatively and socially, that they ultimately have.

The last vestiges of colonial power also underline Rory Kennedy’s latest, The Last Days in Vietnam, an excursion into the impossible moral choices that visited the last group of American diplomats and soldiers who remained in Saigon as South Vietnam fell to the North. With their hands tied due to the effectiveness of the anti-war movement and the general weariness of the American public to spend any more on a bloody war fought on false pretenses, the Ford Administration had no means of helping the South any longer. On White House orders to evacuate only U.S. citizens, even as hundreds of thousands of their South Vietnamese collaborators, from government officials to civil servants, faced certain danger and death at the hands of an increasing brutal North Vietnamese force, a small coterie of actual U.S. war heroes, including such notables as ex-Deputy Secretary of State and Valerie Plame affair bad guy Richard Armitage, tried to save as many lives as they could. In a particular harrowing account (despite the film’s rather stultifying over-reliance on interweaving, without much imagination, talking heads and archival footage), Armitage, captaining the USS Kirk, manages to save over 30,000 South Vietnamese refugees.

Debuting in the Documentary Premieres section at Sundance, the movie is polite but not terribly incisive critique of American power and its various misuses; in that way, it is similar to this scion of liberal royalty’s breakthrough Sundance excursion, 2007’s The Ghosts of Abu Ghraib, which suggested that culpability for that prison’s heinous war crimes most likely went all the way to the very top of the American power structure but refused to truly grow angry about it. Despite its mainstream TV-ready sensibility, it’s got some candid moments of reflection from a lot of men who were placed in truly awful circumstances and ultimately could make you think long and hard about the bitter responsibilities that those who wage war in lands far from their own have to the collaborators they leave behind when the tides of battle turn against them both.

What are the wages of fear? Is the line between media sensationalism and legitimate reporting ever more blurred than when sex is involved? Are forgiveness and love truly the responsibilities inherent in Christianity? These are some of the questions, but certainly not all, that Jesse Moss’ remarkable U.S. Competition Doc The Overnighters poses. The film visits the town of Williston, North Dakota, the seat of Williams County, a once sleepy hamlet of just over 14,000 that has been besieged by outsiders, mostly unemployed men, many with checkered pasts, who have journeyed there to work in the vast oil fields that have opened across the Northwestern party of state due to the emergence of fracking.

Jay Reinke, pastor at the Concordia Lutheran Church in Williston, North Dakota, husband and father of two, sees it as his Christian duty to counsel and provide shelter for the most desperate of these men, many of whom took up residence in their cars and RVs in Concordia’s parking lot, drawing the ire of neighbors, local officials and many members of congregation, whose ranks begin to thin out as he allows the men to sleep on the floors and in the pews of the church. Often his work with the men requires him to stay away from his family for long, seemingly intolerable hours, as he more or less manages a motel in that basement of his house of worship; as the film tells us in its closing cards, over a thousand people stayed the night at Concordia during a two year period, and many more slept in the parking lot. This influx causes quite a bit of distress in the rather homogeneous community. With much haste, the city government commences a plan to people from sleeping in RVs in parking lots and city streets for more than 48 hours in order to stem the tide of people that Jay and his ministry seek to help.

This magnificent doc, observant and true, is no simple tale of a do-gooder however. Just as it seems Jay Reinke is the last man keeping alive the original intent of Jesus’ message in this stretch of prairie, Moss’ documentary presses deeper still, revealing chilling ambiguities in Reinke’s work with these often broken oil prospectors. When the local paper, the Williston Herald, reports that several men staying at the Concordia, including one whom Reinke has personally housed at his residence, are sex offenders, the community begins to turn against his work with increasing vehemence. We watch him do his best to hide this information from the public, and later to assure neighbors that the men in question are not dangerous, that they have been reformed; the footage of his interactions with them doesn’t suggest otherwise, and indeed the The Overnighters offers penetrating moment after moment of Reinke’s sincere ministering to abuse victims and drug addicts, men who have never been loved by anyone and never given a chance to self-actualize. But it’s Reinke’s own sins and need for redemption, peeled delicately back as if an onion over the picture’s 110 minute running time, that are the most harrowing revelations, ones I won’t reveal here. If not calling into question the essential goodness of his work, they certainly give us a sense of why he would be so willing to spend his time in the company of derelict men versus what is obviously a loving family.