Back to selection

Back to selection

Last Looks: The 2014 Locarno Film Festival

Horse Money

Horse Money [Paul Dallas’ first report can be read here.]

Time wasted and time well spent — a ratio every festivalgoer has to work out when gambling on what to see and miss. At Locarno this year, one had to decide whether or not to devote five hours and forty minutes to a single competition film, the equivalent of four Italian classics from the wonderful Titanus retrospective. It wasn’t easy when the former was Lav Diaz’s From What Is Before, an early frontrunner and eventual winner of the Golden Leopard, and the latter all screened on 35mm — an increasingly powerful incentive to skip the new in favor of the old at festivals today.

I found myself doing more of this kind of math during the 67th edition of Locarno. It wasn’t that there were fewer great films, but that they were somehow more sporadic. Other than Diaz’s film, which fans generally agreed is stronger than 2013’s Norte, the End of History, there never emerged a consensus favorite on par with last year’s What Now? Remind Me. Most films, it seems, fell between praise and a shrug. During the first week, there were critics who lavished compliments on Eugène Green’s La sapienza, an idiosyncratic drama about Baroque art and a middle age couple’s reawakening. Others (myself included) couldn’t connect with its highly mannered filmmaking, but New York can judge for itself when the film plays at NYFF.

Debates over the merits of slow cinema and running times, short and long, infiltrated many conversations. Rutger Hauer, head of the short film jury and a champion of less is more, offered the blunt observation that most features today would do better as short films, “because they take forever telling a thin story and make me fall asleep”; good thing he wasn’t on the main jury. Lav Diaz offered a more generous perspective in his Q&A when he said, “Cinema can be one minute or twelve hours.” He has yet to make a one-minute film (to my knowledge), but the synopsis of From What Is Before in the festival catalogue was impressively succinct — about the length of a Tweet.

Hauer’s remarks might strike some of the regular Locarno crowd as unfashionable but were echoed privately by critics and journalists who complained about slight films, and recommended certain ones based on minimal time commitment. (“Yeah, you should see it. It’s only 70 minutes.”) Whether this was due to over-stimulation or attention deficit is anyone’s guess, but I sensed a degree of fatigue with the current grammar of “serious” cinema. I found myself yearning to see more exuberance and riot in works of the emerging directors.

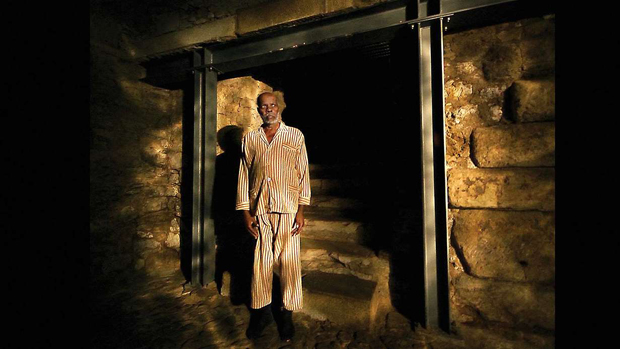

As it happened, Pedro Costa’s very serious Horse Money — one of the festival’s most anticipated films — saw the director experimenting with a stylized mode. Described by Costa as a “Baudelairian night,” the film is a strange brew indeed, an excavation of personal and historical memory that plays like a theatrically staged fever dream. Set amongst the residents of a psychiatric hospital in Fontainhas, the film explores the trauma of Portugal’s revolution and the country’s relationship to its working class Cape Verdean population. Costa sets the agenda early on with a slideshow of Jacob Riis photos, and the film culminates in a 20-plus minute sequence locked inside a hotel elevator, representing the psychic space of its lead character Ventura. Costa walked away with Best Director and also walked away from Locarno before the awards were handed out.

The most common response to Horse Money seemed to be, “I have to think about it.” While its moody images are stunning, it was Martín Rejtman’s Two Gunshots that cast a spell over me. Oscillating between the banal and the absurd in its portrait of Argentine bourgeoisie, the film’s unease and quiet paranoia are reminiscent of 2012’s Neighboring Sounds. Rejtman’s film begins with sixteen-year old Mariano returning home from an all-night party and shooting himself twice. He survives unscathed, save for a “double sound” produced by one of the bullets still lodged in his body, and heard during flute rehearsals with his Renaissance quartet. Rejtman’s restless narrative moves in unexpected directions and widens outwards, with different characters moving in and out of focus, before circling back to the mystery of the gunshots. It’s the kind of film where a small event like a bird smacking an apartment window comes as a genuine shock.

An ongoing joke in Two Gunshots is the befuddlement devices seem to cause their owners: a gun that won’t stay hidden or an old cell phone that continually beeps. From the look of the devices, Rejtman’s film feels like it’s set in the early ’00s. Olivier Assayas’s Clouds of Sils Maria, on the other hand, is decidedly 2014: iPhones and iPads are continually on display, wielded with finesse by media and Hollywood types incessantly Googling themselves and one another. (The director actually uses these expository gimmicks effectively.) Partially financed by the Swiss, the film screened in the outdoor Piazza Grande in honor of its star, Juliette Binoche, in town to receive the festival’s Excellence Award Moët & Chandon (an appropriate sponsor).

Sils Maria provided one of the more meta viewing experiences at the festival. It begins with Binoche’s pampered movie star arriving in Switzerland to accept an award on behalf of a deceased playwright. It is also shot on location in titular town, located only a few hours from Locarno, and shares virtually the same postcard vistas of the Alps, which Assayas transforms into an existential space. There was a lot to discourage me from liking the film: it depicts a world of hyper-privilege, too-cool personal assistants, and high-end luxury goods, and it comes wrapped in a slick production with Handel on the soundtrack, which makes it feel like the filmic equivalent of a ride in the back seat of a Benz. That’s pleasant, but not how I generally like my cinema. And yet, Assayas manages to create a fascinating pop object that’s both hyper-contemporary and classical. Anchored by a smart script and terrific performances, he has crafted an emotionally honest film about art, celebrity, and mortality in the age of TMZ that’s easily his most satisfying film since 2008’s Summer Hours.

Of course, Assayas is a known quantity; the real excitement at Locarno is the encounter with thrillingly weird and unclassifiable work. This was the case with Fort Buchanan, a short feature by U.S.-born and Paris-based Benjamin Crotty, which played in the festival’s Signs of Life sidebar. Shot on 16mm, Crotty’s film is a kind of queer soap opera about Army wives living on the titular U.S. Army base, where the “wives” are both men and women and the dialogue is appropriated from American TV shows. The cast includes Andy Gillet, Mati Diop and four actresses seen in Bertrand Bonello’s House of Pleasure. Carnal and comic, the film injected some necessary playfulness into Locarno’s line up.

But perhaps nothing at the festival quite rivaled the full-throttle crazy of Copacabana, mon amour, a rarely-screened classic from Tropicália scene made in 1970 by director Rogério Sganzerla. It depicts the anarchic pranks of a trio of outcasts in Rio: bleach blonde prostitute Sônia Silk, her gay brother Vidimar, and his boss (and object of desire) Mr. Grillo. Though in CinemaScope and accompanied by an original Gilberto Gil score, its abrasive aesthetic and display of (largely improvised) bad behavior feel akin to early John Waters. Sganzerla and producer Júlio Bressane apparently shot six such features in as many months; the kids today could learn a thing or two from these guys.