Back to selection

Back to selection

Wanting to Like Everything: The Telluride Film Festival

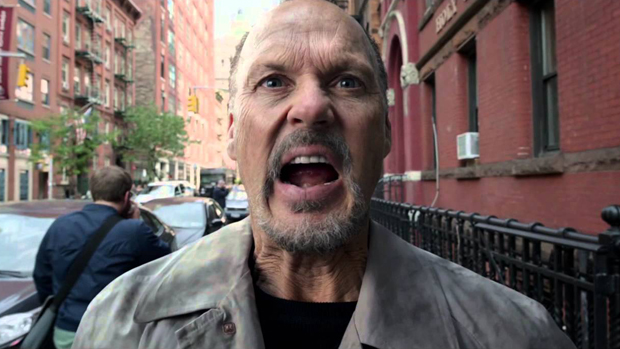

Birdman

Birdman The 41st annual Telluride Film Festival kicked off with a packed screening of Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now featuring Coppola, screenwriter John Milius (still recovering from his debilitating stroke but in great spirits), cinematographer Vittorio Storaro, producer Fred Roos, and editor and sound designer Walter Murch in attendance for a post-film Q&A. It was the kind of event that represents what Telluride does best as a kind of summer camp for movie lovers: presenting a great film impeccably projected before an appreciative crowd in a casual, conversational atmosphere.

There’s something about the environment of Telluride — both the gorgeous Colorado town and the festival itself — that encourages celebrity guests to let their guards down and inspires generosity (at times too much) from the press and audiences. The Q&As tend to be more revealing, the stars and directors more approachable, and the overall quality of the movies more consistent at Telluride than at festivals where more business is being done or where the paparazzi is more pervasive. Distribution deals rarely close at Telluride, and the schedule is never announced until a day or two before the festival begins, so it really is mostly about the movies. Audiences come on faith based on the strong lineups of years past, and directors and distributors bring their films knowing that the fans and press who attend Telluride are an open-minded, enthusiastic bunch who arrive wanting to like everything – snark runs in short supply at the festival.

As in past years, many of the highlights of this year’s festival were the North American premieres of films that screened at Cannes in May. One of the best of these was Bennett Miller’s extraordinary Foxcatcher, a subtle yet extremely unnerving examination of how family, class, and competition inform and are informed by the American dream. Working from an astonishingly layered and complex script by E. Max Frye and Dan Futterman, Miller tells the true story of oddball multi-millionaire John du Pont’s attempt to buy victory for both himself and his country (which, in his skewed view, are the same thing) by bankrolling the U.S. Olympic wrestling team and becoming the benefactor of two gold medal-winning siblings.

As played by an exceptionally creepy Steve Carell, du Pont is a boiling cauldron of insecurity who nevertheless has a spectacularly inflated sense of entitlement — a combination that leads to tragedy for the characters in the film and that Miller uses to say something larger about the schizophrenic nature of American culture as a whole. It isn’t a far leap from du Pont’s neurotic, rambling monologues about American exceptionalism to the blowhards on talk radio who make their living selling the contradictory idea that we are both the greatest country in the world and headed toward unmitigated moral and economic disaster, an idea Foxcatcher examines from a multitude of perspectives with remarkable emotional and intellectual power. Yet it does none of this explicitly: the social and political implications of Miller’s material remain unstated, expressed purely via character and drama. The film’s complicated web of familial relationships and financial transactions yields a movie that’s almost impossible to characterize, a character-driven thriller with no generic contrivances and a black comedy with deep, profound empathy.

99 Homes, Ramin Bahrani’s loose riff on Oliver Stone’s Wall Street, transposes Gordon Gekko and Bud Fox to the 2008 housing crisis. It’s a considerably less successful inquiry into the disintegration of the American dream, though it does boast career-best performances from Michael Shannon and Andrew Garfield. Garfield plays a construction worker evicted from his home by real-estate broker Shannon, who has figured out a way to game the system so that he makes more money after the financial collapse than before it. When Shannon’s character senses Garfield’s hunger and potential, he takes him on as a protégé and gives him (and the audience) an enraging lesson in how and why the principles on which America was founded no longer hold true, if they ever did.

For the first hour or so 99 Homes is flat-out terrific, with razor-sharp dialogue, a documentarian’s eye for anthropological detail, and genuinely difficult moral dilemmas. Yet as in his previous feature, At Any Price, Bahrani is unable to sustain the power of early scenes and cheapens his material with a corny, unconvincing resolution. The power of 99 Homes lies in the magnitude of the horror and injustice that Bahrani so beautifully conveys; when he ties everything up with formulaic melodrama at the end, the impact dissipates and the audience is left with exactly the kind of comforting sense of justice served that the rest of the film has told us is false.

That said, 99 Homes is positively radical and thought provoking compared to the lame satisfactions shopped by Jon Stewart’s Rosewater, which tells the true story of an Iranian journalist imprisoned by Ahmadinejad’s thugs after he releases footage of state-sanctioned violence to the international media. In his pedestrian directorial debut, Stewart manages to drain the story of all but the most clumsy, obvious dramatic effects, relentlessly hammering home a point — that innocent journalists should not be oppressed for speaking the truth — that no one in the audience at whom Rosewater is aimed will disagree with. The bulk of the film consists of scenes between the journalist (an excellent Gael García Bernal, who deserves better) and his captor, who Stewart inexplicably chooses to present as a kind of comic buffoon; as a result, scenes that should be terrifying play like discarded moments from Borat.

Stewart’s film will undoubtedly be mistaken for a work of great “relevance” in the wake of the horrible incidents involving Western journalists and ISIS, but his movie is benefiting from these tragedies, not exploring them – there isn’t a single scene in Rosewater that will challenge or enlighten anyone in the audience who has ever picked up a newspaper. The audience and critics at Telluride seemed to embrace it, but to understand what a failure Rosewater is at every emotion and idea it tries to generate – suspense, humor, a dissection of a rigged political system, etc. – one need look no further than a previous Telluride entry starring Bernal, the exquisite and far superior No.

Rosewater is emblematic of a larger problem at Telluride, which is its relatively recent coronation as an awards season tastemaker. Ever since Slumdog Millionaire premiered at Telluride on its way to picking up a bald swordsman for Best Picture (followed by The King’s Speech, The Artist, and Argo), the festival programmers have seemed to be chasing movies they think will be Oscar contenders, and distributors are in turn chasing down coveted slots at the festival. Every year, there are fewer and fewer truly confrontational films – I can’t imagine something like Larry Clark’s Ken Park, which premiered in 2002, playing at the fest now – and more middle-of-the-road snoozers like Rosewater on the schedule.

The trend is toward good intentions rather than good movies; take, for example, the handsomely mounted but bland The Imitation Game. The true-life tale of Alan Turing (Benedict Cumberbatch), a British mathematician who helped win World War II before being persecuted for his homosexuality, it’s a well-acted, well-photographed, and utterly predictable drama that generates emotion not through craft or intelligence but via an end credit crawl letting us know Turing’s fate. Audiences at the festival ate it up, but it isn’t much of a movie; rather, it’s a plea for tolerance, which places the viewer who doesn’t respond to it in the position of being a jerk, since who wants to be the guy against tolerance? Of course, my argument is that I’m not against tolerance, I’m just against dull Oscar bait like this taking a slot that could have gone to a more interesting film.

Wild, director Jean-Marc Vallée’s follow-up to Dallas Buyer’s Club, gets similarly fraudulent mileage out of having been based on a true story — in this case, that of Cheryl Strayed (Reese Witherspoon), a self-destructive woman who finds enlightenment by hiking the 1100-mile Pacific Crest Trail. The movie is never boring, but it also never adds up to much because the filmmakers seem to see its basis in fact as an excuse to be sloppy with their storytelling. The connection between Strayed’s journey and her inner transformation is never truly dramatized; we’re just supposed to take it for granted because, you know, it really happened. Here’s a test for any movie that begins with the words “Based on a True Story”: if it wouldn’t work without those words at the beginning, it’s not a good movie. Foxcatcher doesn’t even need to tell you it’s based on a true story – it oozes truth from every frame. Rosewater and, to a lesser degree, Wild and The Imitation Game, fall back on the truth as a crutch and fail to transform it into art.

Ironically, the purely fictional Birdman (the best of Telluride’s Oscar aspirants aside from Foxcatcher) feels more authentic than just about any of the non-fiction entries at the festival. This tale of a washed-up movie star (a fantastic Michael Keaton) reaching for redemption as the director and star of a Broadway Raymond Carver adaptation is a smart and hilarious backstage satire that brilliantly skewers just about everyone involved in the production and consumption of entertainment, from actors to critics to the audience itself. A scathing, witty scene in which Keaton’s character faces off against a New York Times theater critic and both diametrically opposed viewpoints are made to seem completely, inarguably correct singlehandedly justifies the entire movie, and there are many equally good moments. In its emphasis on behavior combined with a freewheeling yet meticulous visual style, Birdman was the closest any new film came to the spirit of ’70s gems like Coppola’s – or like Robert Altman’s California Split, presented by guest programmers Guy Maddin and Kim Morgan at a rollicking screening that included a Q&A with star George Segal and writer Joseph Walsh.

Maddin and Morgan’s retrospective picks were among the best films at the festival, as they unspooled relatively obscure works by famous directors like Antonioni (Il Grido), Hawks (Road to Glory) and Losey (the L.A.-set remake of M) and a relatively obscure work by a relatively obscure director (Russell Rouse’s film noir Wicked Woman). Lest I seem like one of those tiresome film buffs who grouses about how much better movies used to be, however, let me say that there was one film at the festival that would stand up alongside the best American movies of the ’70s…or ’30s, or ’40s, or any year or decade you want to name. Tommy Lee Jones’s The Homesman, another carryover from Cannes, is about as good as movies get, a Western with classical virtues that is also a complete original. Since one of its pleasures is its consistent ability to surprise, I won’t give many details about the plot here; it’s essentially a journey film, with Hilary Swank as a prairie woman whose strength is as much a liability as an asset in 1850s Nebraska, and Jones as a claim jumper who accompanies her on a trek east.

As director and co-screenwriter (with Kieran Fitzgerald, adapting Glendon Swarthout’s novel), Jones channels John Ford and Clint Eastwood to evoke stereotypes and archetypes only to dig deeper and get at the truth behind the myths; his film is particularly remarkable in its exploration of the role of women in the West, building on the issues raised by Maggie Greenwald’s exemplary The Ballad of Little Jo. Like that film, The Homesman is a revisionist Western that respects and understands the power of its genre while also understanding the need to question the form’s assumptions. It’s also damned entertaining — funny, scary, rousing, and poignant in equal measures. Kicking off a film festival with a classic like Apocalypse Now is a risky move, in that it sets the bar ridiculously high for all that follows; in the case of The Homesman, however, programmers managed to find a film that both invites and earns comparison with some of the greatest of all time.

Jim Hemphill is the writer and director of the award-winning film The Trouble with the Truth, which is currently available on DVD and iTunes. He also hosts a monthly podcast series on the American Cinematographer website and serves as a programming consultant at the American Cinematheque in Los Angeles.