Back to selection

Back to selection

You Can Take a Horticulture: The Margaret Mead Film Festival

American Museum of Natural History's Hall of Pacific Peoples

American Museum of Natural History's Hall of Pacific Peoples Margaret Mead’s achievements during her 52 years as a curator at New York’s Museum of Natural History have been more seminal than my personal favorite, one that for some unknown reason is close to my heart: persuading the American Jewish Committee to publish a book, driven by interviews with immigrants from Eastern European shtetls, which purportedly created the stereotype of the loving, smothering, guilt-inducing (all that suffering!) yiddishe mama.

More to the point of this article, I also admire her willingness in 1976, on the occasion of her 75th birthday, to lend her name to an annual ethnographic film festival at the AMNH. Over the years it has evolved beyond an assortment of sometimes anachronistic ethnographic docs into a finely curated assemblage of works (less once again proves to be so much more in the 32 programs in this limited edition, which runs October 22-25), that frequently bypass or at the least revise the recherche methods and formats. The directors prove that they have learned from her stress on ritual and the deployment of visual methods in the process of observation, and often the accompanying filmmaking.

A question lingers: Who so finely curates? No names or positions were offered. The films are selected by “folks from the museum, entertainment, and anthropology” is the opaque answer I got from the festival spokesperson, after having been told a day before that works were chosen by the Public Programs Department (translation: they ain’t all film people). Hmmm, I remember when there was a festival director and a structured hierarchy of experts piecing it all together. Did a random bureaucracy replace them? Is this symptomatic of the new branding, the corporation or institution takes credit, not the knowledgeable drones? Are the days of individual recognition (brava, Ms. Mead) a thing of the past? Are the films found objects? Are they sussed out at other festivals, during cultural expeditions — or do they magically appear for preview?

The filmmakers have to appear to face bouquets or tomatoes. Shouldn’t the decisionmakers? The museum lacks transparency. And isn’t this owned by the city? Do I believe that so-and-so is competent enough to pick out for me what I see? Or not? Do you see the NY Film Festival, BAMCinemafest, or any of the other countless film spectacles hiding the experts? I found online that Rachel Chanoff, former director, is still in the game, as is veteran anthropologist Faye Ginsburg. Dominic Davis and Emily Haidet are selectors and festival coordinators (and the main contacts), working with Ruth Cohen, Bella Desai, Kira Lacks, and Adina Williams (festival staff); Pegi Vail, a festival consultant like Ginsburg; and several program consultants (Olli Chanoff, Nadine Goeliner, Oliver Hill, and Charles Jabour). Oh, about 30 prescreeners, two turtle doves, and a partridge in a pear tree. If you really want to know what’s going on, ask some of the better-known trustees: Tina Fey, Tom Brokaw, and everyone’s favorite conservative, David H. Koch (strange bedfellows). Now this is a social structure well worth studying. It’s a little condescending to exclusively take on the powerless while holding yourself above evaluation. Whatever. However. Enough.

In the best way, the experimental infects a number of choices this go-round. This could be more revolution than evolution. Powerful visuals, abstract or otherwise stylistically self-conscious, complement more conventional footage, highlighting the sensorial in order to make our perception more acute, in the service of enabling us to grasp cultures and communities distant from our own. Many of the selections are…artful and edgy! Hip! Shocking! To quote Pokey (Mary-Robin Redd) in Sidney Lumet’s guilty-pleasure film adaptation The Group, “Who’da thunk it?”

Strolling through the neo-Romanesque and Gothic revival building itself is a breathtaking prologue to a movie: 2 million square feet, with 27 interconnected buildings, a planetarium, a library, and 45 permanent exhibition halls, some of which play host to the screenings, as do four theaters of varying capacity. (The Hall of Pacific Peoples is Mead’s baby. Who’s read Coming of Age in Samoa? I haven’t, but I did retread her path in the remote Trobriand Islands, thank you very much, and still have the betel-nut stains on my teeth to prove it.) You would think that one of the criteria for inclusion in the festival is the fit in this grand, monumentally heavy setting across from Central Park.

Below I review two of the strongest films in the exhibition, masterpieces of aesthetic-anthropological integration. Each program screens only once, so you might want to consider buying soon. In both, as it turns out, water is a major player, and greedy outsiders threaten a peaceful, traditional way of life. Screening times follow.

Sailing a Sinking Sea (Olivia Wyatt, Myanmar/Thailand/Moken/USA); Friday, Oct. 23, 7:00 pm

Agile young swimmers, astonishingly shaped and colored underwater flora and fauna, and the abstract and self-reflexive input of a talented filmmaker-artist — Mead’s beloved pictorials — are of a piece in this quasi-avant-garde portrait of the unique Moken society.

A bit of a slave to the underwater camera, Wyatt tracks boys gliding gracefully through the water, usually spearing fish, then transforms the air bubbles they produce, or their overall dynamic into vividly painted imagery, or decorates the space beneath them with bright, sometimes neon forms. She shifts between old video, 8mm, and hi-def digital, scratches the lens, alters the focus. Her still photography is just as sublime. The goal is to call attention to the inseparability of the actual and the invented. There is little gap between daytime realities and a belief system rooted in cohesive mythology.

Wyatt does not use voice-over — none required — only off-camera testimony by these sea gypsies, nomads who traverse the Andaman Sea near Myanmar and Thailand, live on their boats, and hop island to island as necessary. Participants recite narratives detailing the genesis of their metaphysical history. For example, the sun gobbles the stars, his progeny, and takes comfort alongside his wife, the moon. Eclipse! They explain the functions of lightning and rainbows. In addition, Wyatt loads the soundtrack with nearly non-stop eclectic music (guitar, ukulele, chimes, drums) by local band The Bitchin’ Bajas and more traditional melodies.

While the 2004 tsunami brought attention to several devastated countries, it put an unwanted spotlight on the Moken for having survived it almost intact. Adherence to their ancient beliefs and lifestyle saved them: The anticipatory dreams of the elders, in which the seventh and highest of seven waves signals an impending disaster, sent them sailing away from the most dangerous areas. Unfortunately, the victory may contribute to their downfall. Nearby countries have begun to restrict their fishing quotas and their movement, forcing them to live on the islands. (Governments are vicious perps in these films. Ancestors are the the respected authority figures.)

The irony is that their seafaring existence ignores national borders — and that suits them just fine. “We do not like civilization,” comments another man. “We love to live in the water and the natural way of life.” For them the sea cow is sacred (the Moken collect their tears for magical purposes); mermaids are worshipped. The principal requirement for a male to marry is building a boat. “Without the sea, our lives would be lost in competition and confusion,” says one man.

In the few scenes shot on land their games and habits are traditional Moken. They enter trances. When a boy is born, the umbilical cord is hung from a tree, a plea to the supernatural for bravery; for a girl, it is dropped underwater to attach itself to nature. The people are relaxed about sex, affectionately vulgar about the anatomical shrimp and crab. The Moken do not engage in counting; no one knows their own age. Which may be a good thing: Only 3000 remain.

The Shore Break (Ryley Grunenwald, South Africa/Pongo); Sat., Oct. 24, 7:30 pm

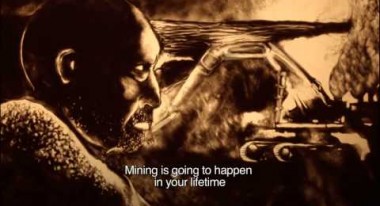

Exceptional sand animation (by Justine Puren-Calverley) and breathtaking cinematography and still photography by director Grunenwald validate Mead’s unending emphasis on the power of the pictorial in cultural anthropology. In this film about overt conflict between agrarian locals and corporate foreign mining developers on the Wild Coast of Pongoland, in the eastern section of the Republic of South Africa, the filmmaker creates art that is infused with ideology, with morality, that helps make a tight case for the righteous in the mind of the spectator. Arguments, community meetings, all forms of oration are ultimately dry, monochromatic. Potent renderings seduce, drawing the viewer in. Rather than detract from the issues, they make the verbiage not only more palatable but also clearer.

The government of South Africa plays hardball in a dispute that should be relegated to the regional level, at best. It does not simply restrict cultural habits as in the feud between national politicians and the Moken in Sailing a Sinking Sea. Exemplifying once again how multinationals trump freely elected bodies in even the staunchest democracies, the federals shockingly nullify the eco-oriented royal family of Pongoland, after citizens unite against potentially lucrative mining plans and a necessary toll road proposed by an Australian concern, Xolco. Their prospectors have found huge amounts of titanium and want to explore and work a 22-km. stretch of beautiful coastal land. The powers-that-be replace the ailing king with an ill-equipped puppet.

The evidence in a town only a few hours drive away disproves the false gung-ho a company exec presents in a series of town meetings. The people there are miserable, the place is polluted, dust fills the air. When the locals appeal the original verdict, it appears that the final decision is a fait accompli in favor of the developers. Xolco buys people with cash and gifts. Several local leaders sell out, accepting the bribes, even cars. Some residents take them because they are poor.

The elders, however, recognize short-term gains, and what the invasive technology would do to their ancestral lands. Some of those opposing the plan are assassinated. The great unknown who galvanizes the “no” forces is a highly articulate, intelligent travel agent named Nonhle Mbuthuma, a woman fearlessly motivated to preserve ancestral lands. The cocky Aussies and even some local politicos are shocked by the sentiments expressed by most of the farmers. “We like our mud houses,” says one man. They do not want to alter the quality of life that they, and their ancestors, have enjoyed in this place.

The pro-mine faction is led by the charismatic Zamile Qunya, aka Mandiba, a clever, fairly westernized hustler who only sees money to be made. He insists that mining and tourism can coexist. The Judas of the Pongo, he also happens to be Nonhle’s cousin. Dramatically speaking, this is manna in a culture where the ties of kinship are quite binding.

Shades of apartheid, a second group of opponents takes on Xolco. They are all white, hang out together in a particular pub. Some are more committed to the cause than others. One man is a smart social worker who has been an activist in the area for many years. A young couple are lodge owners suffering from the downturn in tourism stemming from the rising tension between factions. The publican is a classic liberal, looking through rose-colored glasses at the pluses, like the hospitals he assumes a good road would bring them.

Ever the devil’s advocate, Nonhle points out that the proposed highway completely bypasses their town. She notes that, in the meantime, basic facilities have been intentionally held back from these rebellious people. One of the boldest works of sand animation is a narrative of the plight of a sick 12-year-old girl, who dies after she finally reaches a hospital, following a five-hour trek. Animation pops up at significant moments, like the assassination of a dissident and the death of the king; around charged issues, like a depressing view of a working mine; and in bursts of fantasy, like a recurring symbolic bull on the beach.

The momentum leads to the highest court, in Johannesburg, where the residents attempt to overrule the lower court’s decision to replace the beloved royals. No spoiler here, but once a ruling is made, the citizens opt to get rid of their treacherous chief. Nonhle is the most verbal opponent of the shameless man, who cares little about his people. He is like Mandiba, but without personality. The Shore Break plays like a classic western: bad guys overrun a town, the marshal (here a woman) organizes the slightly odd civilians to send them on their way.